Britain, Yemen and the price of love: Migration rules punish families torn apart by war

"It was very hard, especially when you're a single mum. My kids were born in the UK and they haven't lived with their father for the whole of their lives."

"This one," she says, pointing at the youngest, "did not meet his father until he was almost two years old."

After four visa applications, the last of which she won on appeal, she was out of pocket by several thousand pounds.

"This last one on its own cost me £4,000. I spent about £15,000 all together. I had to take out loans and ask my family for help. If it wasn't for them, I don't think I would have been able to do it. I am in debt by about £12,000."

The fee for a spouse visa application is £1,464, plus £600 for an NHS health surcharge, and £490 if you want to "fast track" your bid.

If rejected, the sponsoring partner can appeal to a migration tribunal for an independent review of the Home Office's decision - but only at the apellant's cost. Solicitors get involved, and families can easily spend several thousand pounds and frequently rack up huge debts.

|

It was very hard, especially when you’re a single mum. My kids have been born in the UK and they haven’t lived with their father for the whole of their lives |  |

Alham's older sister, Nedal Saleh, is also a British citizen married to a Yemeni. She is living in Egypt, trying to put together a seventh application after six failed attempts spanning a decade of her life. In that time, she has had serious health issues.

"She had five children who passed away. After the last baby died we had a really strong case, as the British doctors said she literally couldn't give birth outside of the UK," says Amerah Saleh, the third and youngest sister, who has been helping Nedal with the paperwork.

During her last pregnancy, British doctors who operated on her strongly advised her against falling pregnant while living abroad, as they want to monitor the pregnancy from the start to minimise dangers to Nedal or the child.

"She was working here, she had the finances, she had everything in order. [The Home Office] still rejected it. I have been to multiple lawyers who can't find a fault in [the application]."

In the most recent rejection letter, the Home Office suggested Nedal could access private healthcare in Saudi Arabia, and therefore rejected her husband's application for entry to the UK.

But private healthcare in Saudi Arabia is prohibitively expensive, and Nedal was advised against falling pregnant if she can't be monitored from the start.

If she wants to have children, her choice is between living in the UK and being separated from her husband, or to stay in Saudi Arabia with him at potential risk not only to her life, but also to that of any potential children.

"We thought the last time would be the strongest, because she can't move her life ahead. She wants to have children, and she can't," says Amerah.

|

She had everything in order. [The Home Office] still rejected it. I have been to multiple lawyers who can’t find a fault in [the application] |  |

The Home Office has rejected one in three visa applications from Yemeni citizens seeking to flee the war and reunite with their families in the UK since the conflict started, a freedom of information request has revealed. Children are rejected even more frequently, with 35 percent of applications declined. These children are forced to live away from their British parent, often seeking refuge in a third country.

| The Yemeni diaspora by country of visa application. Hover over a country to find how many applied of a visa from there, how many were rejected, including how many children. Data based on a FOI request to the Home Office. All values have been rounded to the nearest 5. Where the Home Office included a value “x” of between 1 and 2, the mean value of 1,5 was used for data analysis. |

Between February 2015 and December 2016 the Home Office received more than 400 applications for "family of British or settled person" visas from Yemeni citizens, 93 of which were for children, a freedom of information request reveals.

This is the legal route for British citizens to bring a partner or child from outside the European Economic Area to the UK.

As part of then-Prime Minister David Cameron's pledge to bring net migration to the UK down to the tens of thousands, the Conservative government in 2012 tightened requirements for people wishing to sponsor a visa for a foreign spouse or child.

The sponsoring partner must have a gross annual income of at least £18,600, with an additional £3,800 for the first non-British child and £2,400 for each additional child.

Alternatively, the couple are required to have substantial savings - £16,000, plus two and a half times the shortfall in the sponsor's earnings. Someone working a (full-time) minimum-wage job, making £7.50 an hour, will earn around £14,600 a year before tax (£2,000 short of the threshold).

The 2012 rules require someone in that situation to have cash savings on hand of at least £26,000.

The government estimated that this would reduce the volume of successful applicants by 40 percent, around 17,800 families a year.

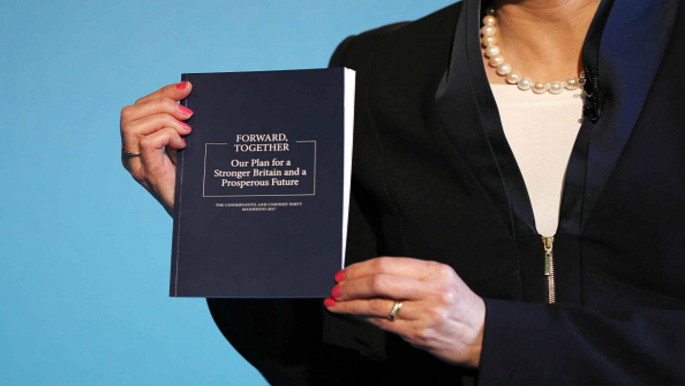

The 2017 Conservative manifesto promised to further "increase the earnings thresholds for people wishing to sponsor migrants for family visas".

|

|

| Theresa May promised to crack down on immigration from outside the EU as she unveiled the Conservative Party's manifesto [Getty] |

This is what groups such as BritCits, campaigning for the rights of international families, call "the price of love", arguing that only rich people have a right to choose whom to marry.

Besides the income threshold, migration rules require applicants to pass an English language test in a testing centre certified by the Home Office.

Meeting the requirements is particularly challenging in a war-torn country. Since popular uprisings in 2011, Yemen descended into civil war. More than 10,000 people have been killed in what has been described by Stephen O'Brien, UN under-secretary general for humanitarian affairs, as the world's "largest humanitarian crisis" since the Second World War.

A coalition of nine Arab states, led by Saudi Arabia, launched an ongoing military intervention in March 2015, conducting airstrikes in support of the internationally recognised president, Abedrabbo Mansour Hadi, against Houthi rebels, who are allied to ousted President Ali Abdullah Saleh and are supported by Iran.

In the first year of airstrikes (March 2015–March 2016), the UK granted export licences for around £3.3 billion-worth of arms to Saudi Arabia, including £1.7 billion in combat aircraft, and more than £1bn of air-to-ground missiles.

|

|

| Protesters contest the sale of 500lb 'Paveway-IV' missiles, currently used by Saudi Arabia's UK-supplied aircraft [Getty] |

Airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition, using British-made Tornado jets and ordnance, are responsible for two-thirds of all casualties in the war, according to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

The British embassy in Yemen closed in February 2015. Since then, hundreds of British citizens married to Yemenis have been separated from their spouses and children, stranded in war-torn Yemen, or displaced in third countries where they have been trying to apply for family visas.

Test centres in Sanaa and Aden were closed due to the war, and people must travel out of the country to sit the test; a journey which is neither safe nor easily affordable.

Alham could not meet the high income threshold, but was recently reunited with her husband by a fortuitous but tragic event.

By the time of her fourth visa application, her father had suffered a stroke and became paralysed. She quit her job to became a carer for him.

Recipients of carers' allowance are exempt from the high income threshold, and Alham's husband was let in on this basis this year.

But as his visa is tied to Alham's continuing status as a recipient of this allowance, Alham is now locked into a cycle of dependency on claiming state-provided benefits - precisely the opposite of the authorities' original intentions.

Whereas Alham's case is genuine, the carer allowance exemption creates a perverse incentive for women to leave low paying jobs and do unpaid, publicly subsidised care work to be reunited with their loved ones.

Another woman, who did not want to be named for fear of jeopardising her ongoing application, quit her job and became a carer for a family friend as a strategy to bring in her husband.

"My daughter is five and she has never been living with her father," she says.

"She also had a few problems linked to this situation. She went through a period when she'd wake up in the middle of the night, and she used to wet her bed and cry for her dad. So to make the application stronger, I told the doctor about it and he wrote a letter, and the letter was included in the application."

The application was rejected, as she did not meet the income threshold.

"I had savings of over £16,000, distress letters, letters from the MP saying that I've been struggling. I had a lot of supporting documents, but I didn't meet the £18,600, and I was rejected."

She then realised that she would be exempt if she took on a carer role.

"Because I was trying to make £18,600, I was working every single day from 8am until 7pm, seven days a week, I had no time for my daughter whatsoever. A family friend was helping with the care work.

"When I looked into it, I realised carers were exempt from that requirement. So now I am working as a carer for my friend. Basically she is doing me a favour, I help her, and that will help me."

|

My daughter is five and she has never been living with her father |  |

Single parents are more likely to claim benefits than a married couple. If a British parent is forcibly separated by their partner because they can't meet the income threshold, there is a higher chance they will have to access welfare support.

The income requirement introduced in 2012 sought to reduce welfare dependency, but appears to have actually encouraged more people to claim benefits.

"This shows it was never really about welfare dependency in the first place. There is very little evidence to show that migrants' spouses disproportionately increase the welfare bill," says Dr Helena Wray.

Wray is professor of migration law at Exeter University. She was the lead author of a 2015 report prepared for the Children's Commissioner, documenting that almost half of the population in Britain would not be able to meet the high income threshold.

|

There is very little evidence to show that migrants’ spouses disproportionately increase the welfare bill |  |

"The welfare argument was an acknowledgement that these issues play very well in the media, that people are very defensive about welfare claims, and that associating welfare claims and migration is a very good way of putting through a policy which otherwise is really very inhumane and might be difficult for people to accept," says Wray.

The high income threshold was recently challenged in a Supreme Court case, on grounds that it infringes upon the right to private and family life, as upheld by Article Eight of the European Convention on Human Rights.

|

ECHR Article Eight: Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence |  |

But on 22 February 2017, the Supreme Court found that the income threshold was indeed compatible with Article Eight, in a judgement which disappointed human rights groups and migration law experts.

The Supreme Court, however, did recognise that migration rules "fail unlawfully to give effect to the duty of the State in respect of the welfare of children".

Judges asked the government to redraft the guidelines given to Home Office employees responsible for visa decisions to prioritise children's interests, a duty imposed by Section 55 of the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009.

"When there are children, their best interest should always be a primary consideration," says Wray.

Her 2015 report estimated that 15,000 children, for the most part British citizens, were suffering distress and anxiety because of separation from a parent due to the new financial requirement.

"What we have is a situation where we have thousands of British citizen children who are forced either to live abroad or to live without one of their parents because of the minimum income requirement," says Wray.

Under Exemption 1 of the migration rules, if a child is British or has lived in Britain for seven years - and it would not be reasonable to expect the child to relocate to the other parent's home country due to "insurmountable obstacles" to family life outside of the UK - a refusal would be a breach of Article 8 rights, and a visa should be granted even if the sponsoring parent can't meet the financial requirements.

|

We have thousands of British citizen children who are forced either to live abroad or to live without one of their parents |  |

"I cannot see how it would ever be in the best interest of children either to have to live in a country like Yemen, or Syria or any other country in that situation, or for the parents to be separated and for the child to have to live in one country. I think the interests of the children are being sidelined unlawfully, and the courts have made that clear... and the government is going to have to change the immigration rules."

| Infographic: Yemeni children of British nationals stranded in third countries. Hover over a bubble to find how many children are separated from their British parent |

Wray also criticises the income threshold for being discriminatory against those demographic groups who tend to have lower wages, primarily women.

"If you are a woman of an ethnic minority living in a deprived part of the UK, the chances that you are able to earn £18,600 are very low indeed.

"If your choice is between working in quite low-paid and perhaps part-time employment, and becoming a carer and claiming a carer's allowance, it creates an incentive to do the latter and does reinforce ideas about women's dependency, and women's caring functions."

Migration rules recognise a further exception from the income and language requirement.

Section 14 of the guidelines for entry clearance officers requires them to assess whether there may be exceptional circumstances which make refusal of a visa a breach of Article 8 rights, or whether there are "compelling compassionate reasons" which might justify a grant of entry clearance, "because refusal would result in unjustifiably harsh consequences for the applicant or their family".

Examples cited in case law include countries plagued by internal armed conflict, humanitarian disaster and collapsed infrastructure. Entry clearance officers don't have the power themselves to grant a visa outside the rules, but they can flag these cases to the Referred Casework Unit in London. In practice, this does not happen.

From 2012 to 2014, only 52 cases were referred for consideration outside the rules, of which 26 succeeded. In the same period, some 30,000 applications were refused, according to government data.

"Nobody in their right mind would recommend somebody goes to live in Yemen or somebody goes to live in Syria at the current time, they're really dangerous places. But the fact is that entry clearance officers, although they are supposed to take these factors into account - they don't seem to do it." says Wray.

"Is the government and are the entry clearance officers acting lawfully? The answer to that I think is 'no'," she adds. "Article Eight of the European Convention on Human Rights requires the government to allow families to live together. If they cannot live in the other state, which it is going to be the case for Yemenis in many cases, it is unlawful to refuse them."

Instead, British-Yemeni families who could be reunited under the "exceptional circumstances" clause are stranded in third countries.

In the four countries which recorded the highest volume of visa applications - Egypt (126 cases), Jordan (90), Saudi Arabia (65) and the United Arab Emirates (25) - Yemenis had a one in three chance of being rejected, also rising to 35 percent in the case of children.

| The four countries with the highest volume of applications for UK visas had a higher than one-in-three rejection rate |

In more peaceful times, the British Yemeni Community Coordinating Committee, an umbrella organisation comprising representatives of British-Yemeni associations, worked on the integration of Yemenis in the UK and organised charity fundraising for development projects in Yemen.

But since the war started, the leaders of Yemeni communities across the UK have been hearing from distressed families whose relatives are stuck in the conflict or stranded in third countries.

"There are tens of families stranded in Egypt, mainly in Cairo. I know people who have been there for a year, or even a year and a half," says Hashem Abdulgalil, president of the Yemeni Coordinating Community committee. On his last visit to Cairo, he met with a group of 100 stranded Yemenis.

"Before the war, people could just do the [English language] course in Aden or Sanaa and apply for a visa from there, but now they have to go to Egypt or Jordan, rent a flat, do a course, and only then they can apply for the visa."

Many people had not intended on returning to the UK but were forced by the war to flee Yemen.

"Most people here are on minimum wage, and it is really hard to achieve the £18,600 [threshold]. We would like the British government to recognise the situation and to look at it in a special way. It is really difficult for those families to come over," says Abdulgalil.

Kamal Mashjari is the cultural manager at Liverpool's Al-Ghazali centre. A software engineer and a proud scouser, he is a member of the fourth generation of the Yemeni diaspora that arrived in this port city in the late 1800s.

There are between 70,000-80,000 British citizens of Yemeni descent living in the UK, forming the longest-established Muslim group in Britain, according to the BBC.

"There is a picture of my grandfather in the Liverpool Museum," Kamal shares, proudly.

When the coalition began bombing Yemen, Kamal's brother and two nieces were in Sanaa with their Yemeni mother.

"My younger brother had to leave his wife and children to come back here and get a job to try and make the amount of money necessary. His wife is pregnant with their third child and he is not there," says Kamal.

"He had been living in Yemen for nine years and had no intention of coming back to the UK. It was just the conflict that resulted into the instability. The cost of living had gone through the roof; some days they had no electricity at all. During the first months of the conflict you couldn't move, you couldn't get food, or water - the situation was dire for most people in Yemen."

Kamal started considering how he could help his brother, and found many people in Liverpool in a similar situation would reach out to him for similar assistance.

He posted a form online for people to describe their situation, and became the go-to person for families with relatives in Yemen - not just for Liverpool, but for the whole UK, and even from abroad.

"We collected just over 200 forms, with just about 250 people on them. We are only talking about spouses or children of British citizens. We are not talking about extended families."

He carries a folder full of case studies. He reads one aloud, in which a worried parent seeks assistance for his four adult children in Yemen. "This is an interesting example: 'Yemen war, no food supply, they lost all their family, their grandad, their aunties. The provider is the elder brother who lately got shot and is unable to provide for them. Their house has been destroyed and currently they have no shelter or anywhere to stay at.' And this is not an unusual case.

"This folder is full of very similar stories of very worried family members. This was a significant amount of work, but we wanted to have the evidence to say to the Foreign Office, 'people are suffering'. Obviously without the data, without the evidence, they weren't doing anything. And even with this information they did nothing anyway."

Kamal presented the forms to local MPs Luciana Berger and Louise Ellman, who in the summer of 2015 presented a petition to parliament asking that the procedures for visa applications be sped up and simplified, that the requirements be reviewed in accordance with the situation in Yemen, and that British citizens stranded in Yemen be evacuated.

Kamal also arranged for his MPs to meet Tobias Ellwood, Minister for the Middle East and Africa at the Foreign Office.

"The response wasn't very good, to be honest. They weren't forthcoming with any of the things that we requested," says Kamal.

Ellwood, when asked for comment for this article, replied: "We try to have as best a system as possible to allow those people who genuinely have cause to come here, but we've had to introduce quite firm rules on migration, simply because of the world that we now live in."

What happened to the 200 applications collected by Kamal? Some of the more well-off managed to get visas, he said. But the majority have not.

"You don't know how bad the government is until you have a situation like this," he said. "They weren't prepared to do the very basic of human decency. We were always told the most important priority is the security of their citizens and yet they have hundreds of citizens in Yemen and they've just been completely ignored."

|

British families are scattered all over the place just trying to satisfy entry commissioning officers, who are making life hell for them. |  |

Abdul Baggash is one of Kamal's cases. His grandson was born under a rain of bombs in Sanaa. His son, a British engineer, managed to get his wife and newborn child to Saudi Arabia, where they have been stranded for two years.

The British embassy granted them a 10-day entry visa to the UK, at which point they became "illegal immigrants". Without a British passport for their child, in a country where they could not officially register, they had to use a neighbour's name to get the baby vaccinated.

|

|

| It took Abdul's son two years to get a passport for his British son and a visa for his Yemeni wife, during which time they were 'illegal immigrants' [Getty] |

"My grandson had fallen sick in Jeddah because he wasn't given access to any medical institution. He contracted respiratory diseases. [When they got to Britain] they had to use a neighbours' name who had a similarly aged child. That's how bad it was," says Abdul.

Abdul applied three times for a visa from Liverpool, and on the third time won the case on appeal.

"It cost us around £28,000 from the day they left Yemen until when they came here. I think the Foreign Office should appreciate these people are in deep trouble. They are not under any circumstances trying to fiddle with the law, they're not asking visas for anyone - just for their direct family members, their wife and children.

"British families are scattered all over the place just trying to satisfy entry commissioning officers, who are making life hell for them."

Smit Kumar and Hans Appadu of OTS Solicitors are migration specialists.

Kumar says that by rejecting so many Yemenis, "the Home Office is making unfair decisions".

"Yemen is a war-torn country. If there is constant fear, if the child doesn't get an education, if there are food issues… of course that's a breach of all rights - Article Two [the right to life], Article Three [freedom from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment], Article Eight [right to private and family life]. It becomes an exceptional case in itself. But it has to be argued," says Kumar.

|

In the tribunal, when a Home Office representative wins a case, they become a supervisor. If they refuse cases, some of them can become supervisors |  |

The burden of proof is on the applicant. Often people hurt their case by applying for other types of visas - such as visit visas or student visas - feeling they would be easier to obtain. In fact, each time they are rejected, it weighs upon any future application.

"It is important to get the application right from the start," says Smit. "But in our experience, more people are allowed in at the stage of appeals in front of the tribunal judge."

But an applicant must first have the resources to bring an appeal to be granted a visa on the grounds of human rights. This is not only costly for them, but also seems inefficient from the point of view of the Home Office.

"Entry clearance officers just check the guidelines - but it seems they are not updated with most recent changes in immigration law- for instant some ECOs are still referring to EEA Regulations 2006 when considering EEA applications which is not correct post Feb 2017," explains Appadu.

"Immigration keeps changing every day, every day there is a case in the upper tribunal which becomes binding. Some of them, they don't even bother to check.

"They just don't care, if they see something tiny, they refuse it, because they have to protect themselves. And maybe they are being guided - it might be the case, if they refuse cases with good grounds, they might be promoted to senior entry clearance officers.

"In the tribunal, when a Home Office Presenting Officer [HOPO] wins a number of cases, they might become senior HOPOs. If they win cases, they increase their chance of becoming supervisors or senior HOPOs."

In 2014, a Home Office scheme rewarding entry clearance officers who rejected asylum claims with shopping vouchers was exposed by The Guardian. Such incentive schemes devised to meet migration targets cast doubt on the fairness of the system.

"If you see some decisions, they are very unfair," says Appadu.

Asked to comment for this article, the Home Office gave us the following statement:

"All applications are considered on their individual merits in line with the Immigration Rules. The minimum income threshold for British citizens sponsoring a spouse visa has been upheld as lawful by the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has asked us to look again at how we deal with exceptional cases and cases involving children.

"Applications not meeting the current rules are temporarily on hold while we do so."

Paola Tamma is an investigative journalist. Follow her on Twitter: @paola_tamma

This article, first published on June 13, was updated on August 14 to clarify remarks from Hans Appadu of OTS Solicitors.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News