Iran's presidential race heats up on eve of polling

The political temperature has been rising for the past week after the incumbent, Hassan Rouhani made a clear shift to the Left in terms of his international, social and moral politics.

He accused his main opponent, Ebrahim Raisi, of knowing "only execution and imprisonment", a clear reference to his involvement in the mass execution of more than 5,000 Iranians in 1988. Raisi's campaign responded by accusing Rouhani of leading a corrupt and divided state, doubling down on prior accusations.

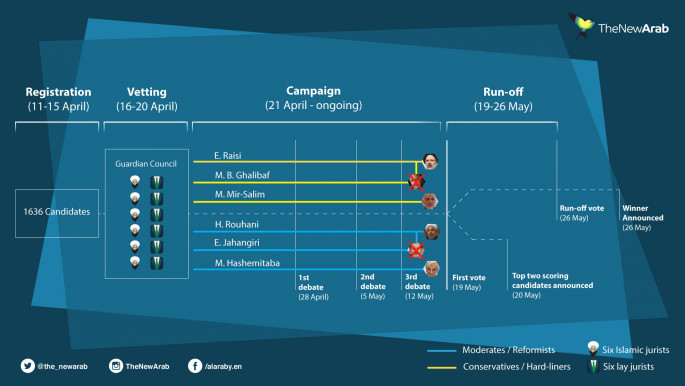

On May 12th, the six candidates arrived at the debate determined to leave no stone unturned. The conversation was heated but civil, and mostly revolved around the economy. Questions included what each candidate would do about smuggling, how they would boost consumer spending, develop exports, and deal with the problem of tax evasion.

Accusations were fired from each side. The main targets of attack were frontrunners Rouhani and Raisi. Rouhani doubled down on his attacks on the conservatives, accusing Ghalibaf of wanting to beat students, and Raisi of exploiting religion. The conservatives responded by reiterating their accusations of corruption against Raisi and once again attacking his economic record.

In terms of foreign policy, most candidates struck a progressive tone. All except Mir-Salim, who insisted on the importance of international investments in Iran and mostly avoided aggressive rhetoric against other countries.

|

Rouhani is still polling better than his rivals, but he sees the warning signs on the horizon |  |

Rouhani's job was to look confident and competent, and to give his supporters a reason to show up at the polls. He managed this quite well. He was aggressive but respectful, and at times managed to land a blow from which neither Raisi nor Ghalibaf recovered very well. Rouhani's assertion that Raisi was abusing religion to gain votes wasn't met with a full-throated defence of religious values, nor was Rouhani attacked for being too soft.

Raisi had to recover from his initial lacklustre debate performances. His job was to stay focused and make Rouhani look incompetent and corrupt. He seems to have managed to do so relatively well, for example by drawing attention to Rouhani's brother, Hossein Fereydoun, who has been accused by conservatives of being corrupt.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

This, paired with the conservatives' continued assault on Rouhani's economic record and increased unemployment, could prove fruitful.

Since the majority of Iranians see unemployment as the most important issue facing the country that Iran's next president should try to address, it's no surprise that the conservatives have pegged this as Rouhani's greatest weakness.

|

Rouhani's future especially, is in the hands of progressive voter turnout |  |

On 15 May, just a few days after the debate, Mohammad Ghalibaf dropped out and endorsed Raisi, who then became Rouhani's most important challenger. Ghalibaf's exit wasn't entirely unexpected: He'd been lagging behind his main rival in the conservative camp, Raisi, and hadn't managed to pick up much support from undecided voters.

Just a day later, Eshaq Jahangiri, the current vice-president, followed suit by also dropping out and endorsing his boss Rouhani. He had been accused of being in the run just to help Rouhani, and he likely decided to wait for one of the conservative/hardliners to drop out first.

Mostafa Hashemitaba, the other reformist candidate, also expressed his support for Rouhani, but has not formally dropped out.

|

These rapid-fire developments have turned the election into a two-horse race between Raisi and Rouhani |  |

These rapid-fire developments have turned the election into a two-horse race between Raisi and Rouhani. The results are difficult to predict. After Ghalibaf dropped out, both candidates have been gaining support. According to an IPPO-group poll, about 61 percent of likely voters say they will vote for Rouhani. Raisi comes in second with 23 percent.

At the same time, about a quarter of respondents are still undecided, leaving plenty of ground for Raisi to gain. About 18-20 percent of poll respondents didn't want to indicate their preference, meaning that the total percentage of people whose voting preference isn't known is over 50 percent.

| Read more: A who's who of Iran's presidential candidates | |

Another poll by the Iranian Student Polling Agency (ISPA) from 13 May (before Ghalibaf dropped out) put Rouhani at 43.2 percent, Raisi at 24.5 percent and Ghalibaf at 21.7 percent among undecided voters. Among decided voters, Rouhani gets 47.2 percent, Raisi 25.2 percent and Ghalibaf 19.5 percent.

Everything points to a very close race assuming that Raisi will pick up most of Ghalibaf's voters. The large number of undecided voters, as well as the number of people unwilling to state their preference complicates things even further. All this makes the election impossible to predict with any reasonable certainty.

|

While all these endorsements may look like a positive thing for Rouhani, there's a risk they might backfire |  |

Both candidates have been finding support from outside of the candidate pool as well. Rouhani was endorsed by Oscar-winning film director Ashgar Farhadi on Sunday. Former reformist president Mohammad Khatami also urged Iranians to "once again" make Rouhani president.

Then, one of the leaders of the Green Movement that challenged Ahmadinejad's victory in 2009 in large-scale protests, Mehdi Karoubi (who has been under house arrest since 2011), also announced his support for Rouhani.

The most important endorsement, however, came from former Green Movement leader Mir Hossein Musavi. Still under house arrest after his role in the 2009 demonstrations, Musavi remains a hugely popular figure.

| Read more: Iran elections 2017: A new direction for foreign policy | |

As such, Rouhani has kept to his strategy of moving to the Left in order to appeal to disenchanted urban and progressive voters, in a bid to avoid a low turnout that could potentially be lethal for his aspirations. Rouhani is still polling better than his rivals, but he sees the warning signs on the horizon.

Although economic growth is projected to be good, the effects of the lifting of the sanctions haven't yet been felt by the general population, and the opposition has used this as a hammer against Rouhani's chances.

However, while all these endorsements may look like a positive thing for Rouhani, there's a risk they might backfire. Support from such controversial figures, especially Karoubi and Musavi, will anger hardliners and establishment conservatives.

|

Rouhani has kept to his strategy of moving to the Left in order to appeal to disenchanted urban and progressive voters |  |

This might not only galvanize hardliner/conservative voters, but could also draw the attention of the Revolutionary Guard, to try to rig the election against Rouhani for fear that he has become too liberal. This would spark a fierce response from Iran's reformists, who are already on edge and wary of conservative and religious encroachment.

A repeat of 2009 is not outside the realm of possibility, and the Green Party leadership's public endorsement makes this more likely.

As there are now fewer candidates in the race, chances of a runoff have decreased precipitously. This means that Rouhani's future especially is in the hands of progressive voter turnout. If he manages to galvanize enough support and get a good deal of apolitical Iranians to show up and vote, he will win.

If not, Raisi's chances are by no means bad. The final complicating factor is the potential for escalation; if the Revolutionary Guard or members of the political establishment try to rig the election in favour of Raisi, there's no telling how the reinvigorated Green Movement and its allies will respond.

Behnam (Ben) Gharagozli received his BA with Highest Distinction in Political Science from UC Berkeley and his JD cum laude from UC Hastings College of the Law. While at UC Hastings, he served as Development Editor of the Hastings International and Comparative Law Review.

Follow him on Twitter: @BenGharagozli

Jon Roozenbeek is a PhD candidate at the Department of Slavonic Studies at the University of Cambridge. He studies Ukraine's media after 2014. Before coming to Cambridge, he worked as a freelance writer, editor and journalist.

Adrià Salvador Palau Is a PhD candidate in the Distributed Information and Automation Laboratory at the University of Cambridge. He has written several journalistic articles about politics and international relations. He is interested in how data science can be used to better understand political dynamics.

Follow him on Twitter: @adriasalvador

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News