Jewish Arabs and the birth of Israel's Black Panthers

I meet Reuven Abergel in a

Reuven's Musrara became a byword for Mizrahi disenfranchisement. It was little wonder that the neighbourhood was where Reuven and fellow activists Saadia Marciano and Charlie Biton would launch their Israeli Black Panthers group, following the failure of the Labor government - and in its previous incarnation as Mapai - to sufficiently tackle the grievances brought up by these Jews from Arab lands in protests like that in Haifa in 1959.

The movement, founded in 1971, was influenced by a meeting held with the founder of the American Communist Party and close associate of American Black Panthers, Angela Davis. And much like Ethiopian Jews in Israel today have connected their struggle against violence and discrimination to the Black Lives Matter movement - Abergel and his friends thus identified similarities between the plight and efforts of African-Americans to gain full civil right status in America with those of North African and Middle Eastern Jews to gain equality within Israel.

The Musrara neighbourhood is where Reuven made his first foray into political activism. And where, in July 1959, he handed out posters and signs in support of Moroccan residents in another district, the Wadi Salib district in

The Israeli government had settled the former Arab neighbourhood with immigrant communities of Sephardim and Mizrahim - Jews of Iberian and "Oriental" origin - mainly from

Much like the neighbourhood of Musrara where Reuven grew up, Wadi Salib was a neglected locale - many of its Moroccan Jewish residents were unemployed and poverty was rife.

Failure to see a marked improvement in their lives following ten years of calling

If social malaise of the immigrant Moroccan community was a long-held grievance, the shooting by police of unarmed Yaakov Elkarif on July 9, 1959, brought these feelings to a fore. To the residents of Wadi Salib, their socioeconomic status and Elkarif's shooting illustrated how an Ashkenazi-dominated establishment not only cared little for their concerns, but had no qualms about harming them arbitrarily. Rumours circulated that Elkarif had died - he hadn't, but he was seriously injured.

The morning after the shooting, Wadi Salib residents marched to the affluent

Before Haroush's arrest, other riots had broken out on 11 July 1959 in other Israeli towns and cities with largely Mizrahi populations, including

|

The fact that many Middle Eastern Jews... spoke Arabic, the 'language of the enemy', increased suspicion |  |

Wadi Salib was the earliest case of widespread internal insurrection within

They alleged that post-1948 Ashkenazi olim - including Romanians and Holocaust survivors from Europe's postwar displaced persons' camps - received favourable treatment; even though their mastery of Hebrew was no better, and in many cases much worse, than that of Mizrahim.

|

|

| The radical socialist Israeli anti-Zionist group Matzpen was the focus of a 2003 documentary |

Many Mizrahim found themselves marooned for years in dingy ma'abarot, or absorption camps, or dispersed to less secure border settlements on

Several other elements bespoke discrimination: the notion, often fictitious, that Mizrahim were generally poorly educated and thus liable to be an economic burden; and the idea that the "orientals" were not "Zionist" in the modern sense - often true, but no different from most refugees from Hitler in the 1930s.

The mostly secular Labor Zionist establishment also disparaged the average Mizrahi immigrant for being traditionally religious - hence "backward" in the eyes of the most zealously "progressive" Laborites.

Lastly, the fact that many Middle Eastern Jews - especially those from Iraq and Yemen - spoke Arabic, the "language of the enemy", increased suspicion among the Hebrew-speaking population, and made many Mizrahi children feel embarrassed at their parents' ways.

By and large, the legend of a united Jewish people prevailed during the decade followed Israeli independence in 1948 - years when the Israeli population literally doubled, and millions were spent on absorbing the new arrivals. Thus the events of July 1959 were a jolt to the relatively new state of

The idea that Jews would be violent and cause destruction in a Jewish homeland that offered them sanctuary went against the grain of thinking within the establishment.

Reuven explains that Wadi Salib was a shock to the Mizrahim, too, with "elders in the Mizrahi community realising that

The events in

Reuven maintains that the protests at Wadi Salib marked a critical moment for Moroccans, in particular, and their relationship with the Israeli left. The protests in

According to Reuven, Wadi Salib offered a platform which began a process that offered Arab citizens of

"The atmosphere of Wadi Salib opened a space for both the Mizrahi protest movement and the Palestinian movement," he says. "The Black Panthers' activities were an important juncture for future civil rights protests, and both Mizrahi Jews and Palestinians need to acknowledge this, as both are important for peace."

|

The Labor government feared that such a bond between Matzpen and the Black Panthers could one day lead to its downfall |  |

Reuven makes it quite clear that he does not want to detract from the inroads that Arab-Israelis have made and the Palestinian national movement in their struggle for equality and statehood. Reuven believes "100 percent... that a Palestinian and Mizrahi union would end the conflict in

Above all, he feels that a revisiting and understanding of the two groups' shared linguistic and cultural heritage is crucial for any future peace.

Although the state always regarded the Black Panthers as a fringe movement, they did nonetheless see the group as having the potential to become a much larger political force. Though, it was not a possible alliance between the Black Panthers and Palestinians that worried the Israeli establishment, but rather the threat of a mutation into

|

|

| Activists renamed another of Musrara's streets after Meir's infamous quote [WikiCC] |

Prime Minister Golda Meir's almost innocuous reference to the Panthers as "not nice boys" after meeting with them in April 1971, belies the serious threat that her and previous governments felt would come from a Mizrahi-Left coalition. The Labor government felt that such a challenge would come from an alliance that coupled the Black Panthers to the socialist Matzpen organisation.

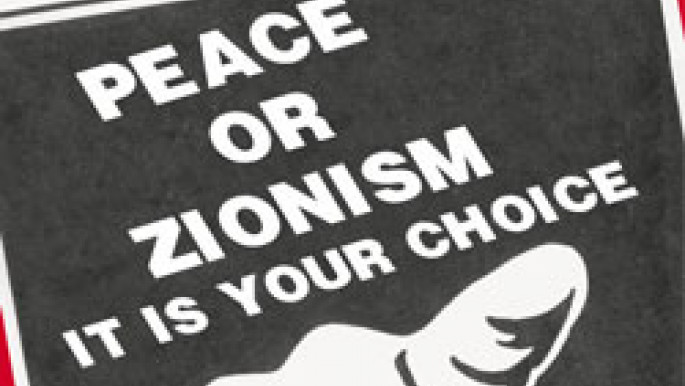

Matzpen's anti-Zionist stance and its solidarity with the Palestinian struggle for national liberation was already a cause for concern for the state, which sought to target members through smear campaigns in the media, and occasionally by force through the state's security apparatus.

The Labor government feared that such a bond between Matzpen and the Black Panthers could one day lead to its downfall, and this sense of alarm led to a sustained effort to demonise both. As a result of this persistent state-driven campaign, the two groups ultimately saw their capabilities and wider appeal diminish - though not before the Panthers were able to gather 7,000 civil rights activists in

That night of May 18, 1971, marked the defining moment for the group. Later known as "The night of the Panthers", it saw the coming of age of the movements' Moroccan leaders. With 1959's Wadi Salib protest still part of their psyche, the Panthers organised activists who protested against the same marginalisation in

The protesters of

This came in the form of an influx of newly arrived Jewish immigrants from the

Click here for part two of Otman Aitlkaboud's study, charting the rise of the Israeli Black Panthers in a revolutionary age and the group's lasting legacy upon the country's radical and mainstream left.

The two-part series concludes with The legacy of Israel's Black Panthers.

Otman Aitlkaboud is an Executive Committee member of the Arab-Jewish Forum working on improving relationships between Arabs and Jews in the UK and beyond. He formerly worked at conflict resolution think tank Next Century Foundation and for the European Union External Action service in Armenia. Follow him on Twitter: @OtmanA

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News