Mosul's future remains uncertain after a week of fighting

The road leading to the front line is dotted with checkpoints. To cross them, you just need the right number to call. With the authorisation given and the barrier passed, the tarmac road peters out to a gravel path that climbs up into the mountains.

A few kilometres along the dirt road and you can glimpse Mosul in the distance. The sky is clear as Peshmerga forces prepare to retake control of Bashiqa, a town 15 miles north of Mosul.

Once inhabited by thousands of Yazidis, Shabaak and Christians, most of its residents fled when the Islamic State (IS) overran the city in June 2014 as they took over large swaths of the country from neighbouring Syria.

We are inside the military base of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) party’s Peshmerga Force 70, on the extended front line of Bashiqa. The base is just eight kilometres from Mosul and one kilometre from the nearest IS position.

Among the PUK soldiers are several older men. For many of them, including a sixty-year-old who calls himself Colonel Zavaty, this is their third war. One against Saddam and one against the PDK, a rival Kurdish political party.

“I hope that for me this will be the last one,” Zavaty says in fluent French. He is Kurdish but lived in Switzerland for years. He fled Kurdistan and obtained Swiss nationality.

Unlike many soldiers, he doesn’t wear battle fatigues to fight but favours his traditional Kurdish dress instead. “I came here because it’s my duty to protect my land and my people,” he says, shouldering his rifle.

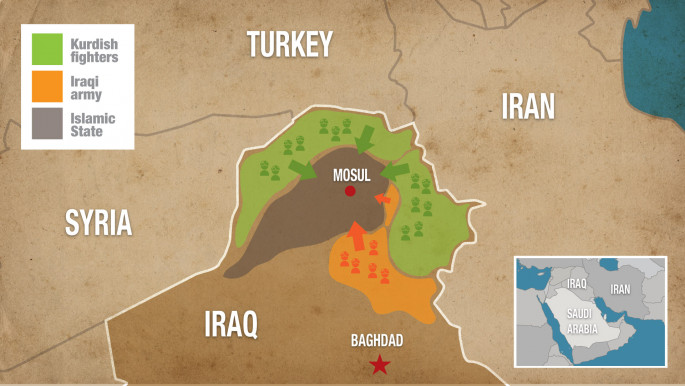

On Monday October 17, as the first light of dawn touched the sky, an Iraqi Army and Peshmerga-led offensive to retake Mosul began. Bashiqa is one of the most complicated and sensitive front lines.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

Here, in this small town, many of the different actors involved in the offensive meet: Peshmerga - divided between PDK, PUK parties, Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs, Iraqi army, American-trained Iraqi counterterrorism forces, Turkmen militias trained by Turkey, American advisors and Special Forces, Canadian, and Turkish soldiers.

While the latter was not taking on a front line fighting role, they had tanks and artillery deployed. Camera-shy, they forced us to delete pictures we took of them.

“So far, we have a good coordination with PDK”, the colonel explains of Kurdish forces loyal to the PUK’s major political rival. “But we don’t advance quickly. There are tunnels, improvised explosive devices and suicide car bomb explosions,” he adds.

Despite coming under heavy attack from IS, the Iraqi and Kurdish troops captured several villages in the first days, most lying to the east of Mosul.

“This is a different conflict,” Zavaty says, comparing his latest deployment to his previous experience. “Before it was a face-to-face war, but today you cannot see your enemy. This is a fight against ideology, so it will be long because IS will not give up that easily”.

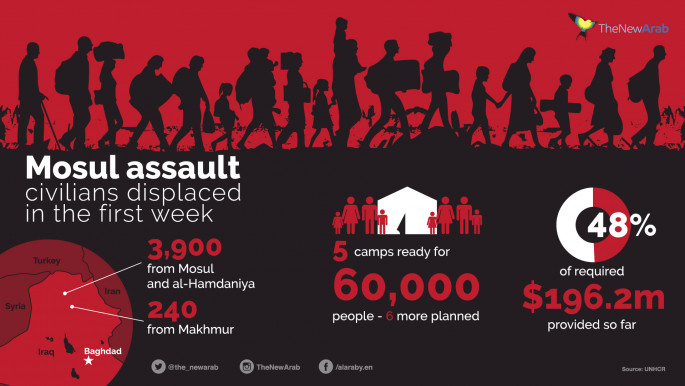

The offensive that started last Monday to capture Mosul is backed by a US-led coalition and is expected to be the biggest battle in Iraq since the US-led invasion in 2003. Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, has been under IS rule for more than two years but liberation comes with challenges – the UN estimate there are more than 1 million civilians trapped inside.

The operation has been marked by a massive and highly orchestrated media campaign. In the run-up to the campaign, speculation was rife over how or when the offensive would retake the militants’ last major stronghold in Iraq. However, after a week into the fighting, the enemy appears more determined and the battles more bloody than predicted.

|

The battle for Mosul, and for other cities still populated with civilians, will not be easy. While some say it will last weeks, others say months. |  |

The Iraqi military and Peshmerga forces have already suffered many casualties. According to an unofficial claim from a Peshmerga soldier, there had been more than forty casualties among Kurdish troops in a single day.

Then came the death of an American service member on the battlefield, followed by two Iraqi journalist – with another in a coma at the time of writing and both a fixer and a New York Times photographer wounded. The ground is full of mines and seemingly empty ghost towns bristle with improvised explosive devices.

On Friday and Saturday IS launched a surprise attack behind the frontlines in the town of Kirkuk, and set an industrial sulphur plant on fire between Qayyarah and Hammam al-Alil, south of Mosul, sending toxic fumes across the region.

IS militants have been using diversionary tactics – sleeper cells, suicide attacks and snipers – to divert attention and confuse the assembled forces facing it. The battle for Mosul, and for other cities still populated with civilians, will not be easy. While some say it will last weeks, others say months.

While Colonel Zavaty is speaking, the explosion of another suicide car bomb is heard. Peshmerga forces respond by firing Katyusha rockets, heavy machine-gun fire and mortar rounds at IS positions.

The pungent smells of lead and smoke fills the air. Not long later the sky darkens. A column of thick, black smoke rises from the IS front.

They are burning oil in an attempt to block the path of the Kurds and obscure visibility for coalition airstrikes. The coalition says smoke is pointless as they use high-tech radar to identify targets.

|

|

While the operation stops its advance for the day, Kurdish commanders insist that they are satisfied with their progress. “It’s ok, we are calm and the soldiers are in a good mood”, says Harem Kamal Agha, a PUK general in Bashiqa.

“Maybe we will take more time, but we will defeat Daesh without any doubt,” he states with a composed voice, using an Arabic acronym for IS. But when asked about his willingness to die for the largely Sunni Muslim population of Mosul, he responds, “No, only for Kurdistan.”

Despite the agreement made by Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani and Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to cooperate over the Mosul operation, there are sill many unknowns, especially regarding the role of Turkey and the numerous other militias and factions on the ground.

Turkey claims the use of Iraqi Shia militias – that were formed to bolster the army after the initial rout as IS invaded the country in 2014 - will displace the area’s largely Sunni population. For this reason it has trained Sunni fighters, known as the Niniveh Guards, and sent troops to the Bashiqa region.

However, the reality appears to be that Turkey wants to keep a foot in Iraq. In particular, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s unyielding stance on Mosul shows he believes it should belong to his area of influence and for this reason he casts himself as the “protector” of the Sunni community.

|

The future of Mosul might still be uncertain after IS, and much will depend on who will be in involved in the final battle and also how civilians fare in the conflict and its aftermath. |  |

After defeating the common enemy, the Islamic State, what will be the future of Mosul and Iraq? In the last year important cities and areas as Fallujah, Tikrit, Ramadi and Sinjar, have been recaptured but how many people have returned to their home? And above all, who now controls those territories?

In Mosul, religious and ethnic minorities – Assyrians, Chaldeans, Yezidis, Turkmen, Shabaak – have fled from the city and they will come back only if they feel safe and protected. But the problem is not only for them. It is also for those trapped and besieged inside the IS stronghold for over two years.

The responsibility to protect these people lies with the Iraqi government and its army. However, the people have little trust in these institutions blaming them for leaving the people in the hands of the IS. Without trust, the much-needed support of civilians during the liberation is also in danger.

The future of Mosul might still be uncertain after IS, and much will depend on who will be in involved in the final battle and also how civilians fare in the conflict and its aftermath.

In an exclusive interview with The New Arab, the Golden Division commander Major-General Fadhil Jalil al-Barwari said that they would not allow any Shia militias to enter Mosul. Despite the claims, the situation on the ground already seems different.

Several Iraqi military vehicles fly very visible Shia flags, highlighting the sectarian division that Iraqi institutions need to mend. If the liberation is lead by militias or troops, which are likely to exercise sectarian violence, the conflict will re-emerge weeks, months or years down the line, leading to an endless cycle of conflict.

Sara Manisera is on the outskirts of Mosul. Follow her on Twitter: @SaraManisera

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News