Why the Middle East cannot ignore the 'shadow pandemic' of violence against women

This year, campaigners who took part in the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence (GBV), which started on 25 November, took on an immense challenge.

Six women are murdered every hour across the world because of GBV, often carried out by partners and family members, in what international rights organisations are now calling the 'shadow pandemic'.

With lockdown measures forcing people across the globe to stay indoors, public demonstrations were cancelled and awareness campaigns have had to be creative.

A new survey carried out by the research network Arab Barometer, in partnership with Princeton University and local groups throughout the Middle East, highlights just how insidious the impact of the coronavirus pandemic has been on gender-based violence in the region.

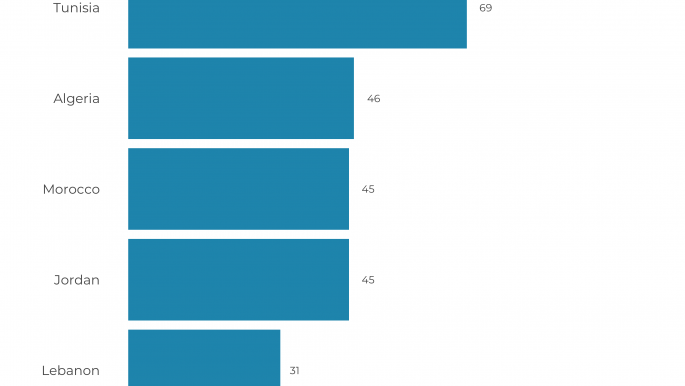

Out of the countries surveyed, Tunisia ranked at the top, with a worrying 70 percent of those polled saying they thought gender-based violence had increased during the pandemic.

Algeria followed with the second-highest figure of 46 percent, while Morocco and Jordan stood at just one percent less. In Lebanon, a little more than a third of people said they had witnessed an increase in GBV. This, partnered with a lack of attention that states in the region are giving to policy and legislation to tackle the problem, could prove a deadly combination for women.

|

In the Middle East and North Africa, 45 percent of all women have suffered domestic violence |  |

"On the surface level it feels like some things are moving, but in the core we know that this [gender-based violence] is now way far from legislators' priority with everything else going on," said Ghida Anani, the Founder and Director of Abaad, a Lebanese non-profit organisation tackling gender-based violence and gender equality.

Lebanon, like many states in the region, has had a difficult time dealing with pre-existing issues exacerbated by the outbreak of Covid-19. In October 2019 mass protests upended Lebanon's stability. Then a massive explosion destroyed the port of the country's capital, Beirut, with Lebanese citizens fighting the worst economic crisis they have witnessed since the country's civil war. Anani said that all these factors have drastically affected the number of women coming to Abaad to seek help.

"At the beginning of the lockdown, women were feeling like they shouldn't prioritise their safety in light of the larger life-threatening situation, political insecurity, the worsening economic situation and the collapse of the banking system, and then the health scare of the pandemic. It was three elements that are essential for survivors to think about before they seek help," Anani told The New Arab.

|

|

| Click to enlarge |

For this reason, Anani and the Abaad team have had to think outside the box.

"We have to keep reaching out to survivors, even if we're not allowed to go to the streets, it doesn't mean they are not in need of our help, so we have to think creatively."

They have since launched an outreach campaign called 'Lockdown not Lockup' to help survivors feel that their safety and wellbeing was a priority as well.

This entailed a promotion of Abaad's hotline number, by having people place placards and signs on their balconies and windows and enlisting influencers to spread the message on social media.

She says the Lebanese state, like many in the region, has struggled to pass effective legislation due to conservative political parties.

Although Lebanon has passed some laws to protect against GBV, legal and safeguarding structures for survivors remain absent.

For example, in 2016 Lebanon abolished legislation that could allow a rapist to escape punishment if he married the victim, but marital rape was not tackled in the same legislation. Lebanon's Article 503 of the penal code defines the crime of rape as "forced sexual intercourse [against someone] who is not his wife by violence or threat", although activists in Lebanon have for years called for the terminology to include rape in the context of marriage.

Anani says that the few organisations that are working on this mission in Lebanon are mainly funded by international parties, and a few by private entities, so the government is not the main actor in providing these services.

In July 2019, the International Commission of Jurists found that Lebanon failed to provide adequate services for survivors of GBV, including a lack of "effective gender-sensitive investigations, effective prosecution, effective measures for protecting," and "adequate capacity and resources."

|

We have to keep reaching out to survivors, even if we're not allowed to go to the streets, it doesn't mean they are not in need of our help, so we have to think creatively |  |

The report also cites issues regarding judicial coherence in addressing GBV cases, and access to legal aid for representation before the courts. The ICJ pointed out how issues of stereotyping and gender biases "against women by justice system actors lead to direct and indirect discrimination against women."

"Furthermore, cultural frameworks and religious beliefs are significant factors influencing women's roles and responsibilities within society. Victims are left to believe that the violations of their rights, especially GBV, are normal, and are, thus, pressured not to complain about these violations in order to protect their 'honour' and family reputation, regardless of the abuse they suffered," the report stated.

Twitter Post

|

Along with Lebanon, other states in the region, such as Sudan, Jordan, and Egypt, have been criticised by Plan International for not having adequate national legislation tackling GBV.

In the Middle East and North Africa, 45 percent of all women have suffered domestic violence – 14 percent more than the global average - according to a 2019 World Economic Forum report.

This ranks MENA as the region with the worst reported figures thus far, and since the start of the pandemic the situation is likely to worsen, with the United Nations citing an estimated 20 percent increase in cases of domestic violence since lockdown measures.

"Without the proper legal and policy protections, women and girls will continue to be under threat in the Middle East. These 'loopholes' and laws need to be changed. There seems to be no political appetite for it especially during the Covid-19 pandemic," Hiba Alhejazi, Plan International's Advocacy and Influencing manager, told The New Arab.

On the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, the UN announced it will spend £19 million of its emergency fund to address gender-based violence against women "displaced by wars and disasters," like those facing devastating conflicts in Syria and Yemen, amongst others.

But with shocking statistics exposing that more than one in three Arab women continue to experience some sort of violence in their lifetime, as cited by UN Women, international organisations say their efforts need to be accompanied by more decisive state-sponsored actions that will place this pandemic high on its list of priorities.

Gaia Caramazza is a staff journalist at The New Arab. Follow her on Twitter @GaiaCaramazza

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News