What can we learn from Edward Said's literature in the thick of Israel's genocide in Gaza?

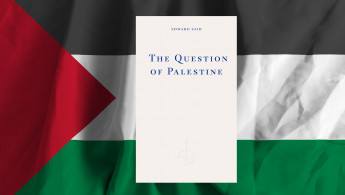

When Edward Said published The Question of Palestine in 1979, he broke an unstated taboo in mainstream North American culture against writing from a Palestinian point of view. Said had just published Orientalism, the book which made his reputation as a literary critic the previous year.

At that point in history, no major public intellectual had clarified “the Palestinian interpretation of the Palestinian experience” in English, as Said described his own goals for this book.

In The Question of Palestine, Said applies the analytical insights of Orientalism to his contemporary political context, thereby revealing the process through which everyday anti-Palestinian racism permeates everyday discourse and shapes foreign policy.

The Question of Palestine had a huge impact when it was published, and yet it seems the lessons Said offers us have yet to be fully learned.

The decision of Fitzcarraldo Editions to republish Said’s seminal book from 1979 alongside his essay The One-State Solution (1999) published two years later in New York Magazine, is well-timed.

Taken together, these two works, accompanied by an introduction by literary critic Saree Makdisi, chart the intellectual journey of one of America’s most insightful commentators on what Said perceptively calls the Palestinian-Zionist conflict.

From his commentary in the aftermath of the 1967 Six-Day War, as the US assumed the mantle of the mediator that would solve this “conflict,” to the ill-fated Oslo Accords of 1993, which enshrined the two-state solution while rendering it obsolete, to his embrace of a one-state solution in its place, Said’s sharp analysis was consistently decades ahead of its time.

In 2024, as the world watches Israel perpetrate genocide in Gaza, it is abundantly clear just how misguided the confidence of successive US administrations that they could bring peace to the Middle East.

In an era when current US President Joe Biden appears unable or unwilling to articulate any credible policy of restraint towards Israel, even when Israel violates US and international law, the US’s inability to act as an honest broker is obvious.

The negative impact of US partiality towards Israel was less obvious to most observers during the 1970s and 1980s during which Said was a unique truth-teller.

Long before most commentators and many stakeholders in the Palestinian-Zionist conflict, Said understood that the Camp David Accords could never serve as the foundation for genuine peace in the Middle East because Palestinians had been systematically excluded from the negotiating process.

As he wrote in 1979 regarding the status of Palestinians in Western discourse and politics: “Palestinians are still perceived […] as a collection of basically negative attributes.”

Dominant political narratives that show Palestinians making “their world-historical appearance largely in the form of refusals and rejections” for much of the 20th century were often used to justify the unwillingness of world powers to support their struggle for self-determination.

The problem of representation that Said diagnosed in 1979 persists today. When European and North American states convene to negotiate peace, they meet with Arab states rather than Palestinian political representatives. At best, they talk with the Palestinian Authority, which is itself a proxy for Israel.

This ongoing bias on the part of US policymakers was reflected in an interview with US-Presidential candidate Kamala Harris in September 2024 during which a reporter pressed her on the US’s unconditional support for Israel.

When asked whether it is even possible for the US, as an ally of Israel, to support Palestinians in their right to self-determination, Kamala countered that she speaks directly with Israel as well as “Arab” officials to construct a “day after scenario.”

In that candid moment, Harris failed to recognise the need for negotiating, not just with “Arabs” in general, but specifically with Palestinians and their political representatives.

Such remarks from a presidential candidate who has been praised for adopting a different “tone” toward Israel show that the dynamics diagnosed by Said in 1979 continue to dominate American domestic and foreign policy.

The broad historical and analytical framework that underpinned the writing of both Orientalism and The Question of Palestine enabled Said to discern the flaws of the US-led “peace process” process far sooner than many regional experts, including many Palestinian leaders and Middle East negotiators.

Another important lesson of Said that remains relevant amid the Gaza Genocide is that the Palestinian conflict is precisely with Zionism, a political ideology that is premised on the denial of Palestinian rights and the appropriation of their land.

Whatever one may say about the rights of states to defend themselves, Zionism is not defensible.

As Said states “to criticize Zionism now, then, is to criticize not so much an idea or a theory but rather a wall of denials. It is to say firmly that you cannot expect millions of Arab Palestinians to go away.”

Because Zionism rejects the possibility of Palestinian existence on equal terms with Israeli Jews, the assertion of Palestinian existence entails the rejection of Zionism.

Said was among the first, and certainly the most consequential of writers, to write about “Zionism from the perspective of its victims,” to invoke the title of the second chapter of his book, which was also published in the inaugural issue of the journal Social Text that same year.

Since, as Said points out, “Zionism has meant as much, albeit differently” to Palestinians as it has to Jews, the Palestinian perspective on Zionism is an essential part of its history and inherent to its meaning.

Later in the book, Said elaborates: “Zionism has been studied and discussed as if it concerned Jews only, whereas it has been the Palestinian who has borne the brunt of Zionism’s extraordinary human cost, a cost not only large but unacknowledged.”

The point is a simple one. Yet, 45 years after Said wrote these words, and amid the genocide that Israel has perpetrated for over a year on the Palestinian people, Said’s words challenge us to confront a simple truth that few outside Palestine have reckoned with.

Globally, Zionism has yet to be understood from the standpoint of its victims, even though our television screens and social media feeds bear to witness the violence it inflicts daily.

Rebecca Ruth Gould is a Distinguished Professor of Comparative Poetics and Global Politics, at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. She is the author of numerous works at the intersection of aesthetics and politics, including Erasing Palestine (2023), Writers and Rebels (2016) and The Persian Prison Poem (2021). With Malaka Shwaikh, she is the author of Prison Hunger Strikes in Palestine (2023). Her articles have appeared in the London Review of Books, Middle East Eye, and World Policy Journal and her writing has been translated into eleven languages

Follow her on X: @rrgould

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News