Suicides rise as South Sudan struggles with post trauma

Some 24,000 people are holed up at a camp for displaced people, located a short drive from Malakal - a once flourishing trading hub reduced to a ghost town by years of conflict.

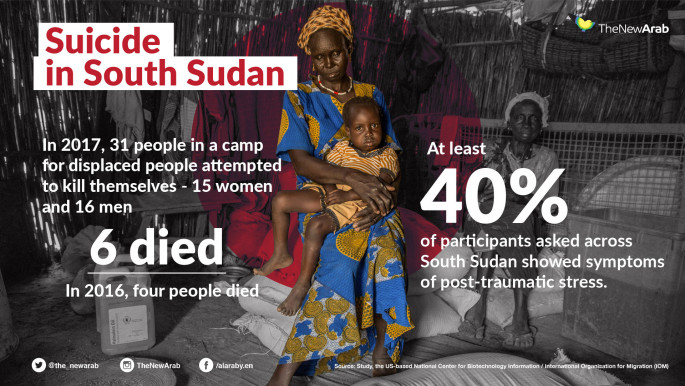

In 2017, 31 people in the camp attempted to kill themselves - 15 women and 16 men - and six people died, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). The previous year, four people died.

Ayak had already lost her four brothers and witnessed countless deaths in South Sudan's brutal war by the time her 19-year-old son was shot in front of her.

Living alone in a miserable structure of plastic sheets and tin at the site, watching as relentless rains turned earth to mud, it all became too much to bear for the 44 year-old.

"I have seen it all. When I thought about the lives of my relatives and their deaths, I decided to take my own life, too," Ayak says, falling silent as tears fill her eyes.

She survived her suicide attempt but is only one of a growing number of people trying to end their own lives in the camp.

In December last year, South Sudan entered the fifth year of a civil war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced some four million people.

With no peace deal in sight, and yet another ceasefire recently crumbling within hours of its signing, many of Malakal's dispossessed have lost hope.

Their previous homes are just a few kilometres away in the nearby destroyed town.

In the camp - known as a "Protection of Civilians" or PoC site - there is no privacy and most families sleep on thin mats on the floor, already dreading the rainy season, due to arrive in the weeks ahead.

Movement is confined to the camp, clustered around a UN base, as many still fear insecurity on the outside.

"People entered the PoC when they were children. Children are becoming adults here and are looking at the future and feel hopeless," says the Danish Refugee Council's country director Raphael Capony.

Hopelessness and PTSD

In a study, the US-based National Centre for Biotechnology Information found that at least 40 percent of participants asked across South Sudan showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

"A lot of problems compound before a person tries to commit suicide.

"Living conditions, a lack of food variety and the difficulty of confinement can contribute to it.

"It's a big burden to not have hope for change," says Raimund Alber, a mental health worker for Doctors Without Borders (known by its French acronym, MSF).

Yet Ayak and dozens of other suicide survivors have given life a second chance. Today she's plugged into a widows' group and receives regular psychological support.

"Many people have the strength to deal with hardship, they have coped with a lot. We're noticing that strength and support it," said IOM psychologist Dmytro Nersisian, who works with Ayak at the camp's support centre.

Aid agencies are filling a gap left by South Sudan's dysfunctional and war-focused government, providing what little mental and psychological support is available in Malakal.

"We've especially seen an increase in suicide attempts since July 2017, which is when we started working on a prevention campaign," Nersisian says, adding that while causes and triggers for suicide vary, people of all ages have made attempts.

Agencies contributed to this report.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News