Retromania and resistance: Record label MaJazz Project reissues new dawn for unsung Palestinian pioneers

In what became a cult classic of musicology, Simon Reynolds’s Retromania describes a Western culture intent on self-cannibalism.

Exhausted by consumerism and technological acceleration, the book claims the West has become a Zeit without a Geist; where the recurrence of older styles has replaced the possibility of innovation. Ideals are defeated by pastiche and futures are stunted by late capitalism’s urge to reminisce.

But while Reynolds can level such a charge at the Global North, can the same be said for the Global South?

"In each cassette reel and crackled vinyl lies not only forgotten Palestinian melodies but the fractured lives of its listeners"

More specifically, can the same really be said about cultural production in Palestine, where to exist is to resist? And can the very things Reynolds labels as problematic – remixing, reissuing, resampling, and reproducing past trends – instead keep the memory of and hope for a Palestinian nation alive?

This is the intriguing story of the 1980s Palestinian folk group Al Fajer, retold by the Palestinian sonic archive, research journal and record label MaJazz Project.

Out of time and place

Mo’min Swaitat, the founder of MaJazz Project, cuts a unique figure among London’s record label owners.

Surrounded by a faceless haze of ‘world music’ aficionados and diggers, Mo’min’s MaJazz Project – a Palestinian-owned label releasing Palestinian music – is a welcome departure from the saviour types that own the repress market.

We all know them. Went backpacking in [insert exotic country here] only to fall in love with the music, returning home with a limited catalogue of the classics. And whilst it’s not our place to judge their motives, it raises concerns about the co-option of imported sounds to a wider, whiter audience.

One look at MaJazz’s releases instead reveals a discography dense with anecdotal histories, sourced by a child of the country with a stake in its future. Its first album reissue, Riad and Hanan Awwad’s The Intifada 1987 proves this identity case and point.

Produced one week after the First Intifada began in 1987 – the first album released after the outbreak of the uprising – The Intifada 1987 was a family effort; utilising keyboards and synthesisers then synonymous with funk to express a DIY initiative now natural to the Palestinian cause.

Despite distributing 3,000 cassettes of the album on the streets of Jerusalem’s Old City, the Israeli Army confiscated all the copies they could, with most continuing to remain in military archives today.

Had it not been for the fortuitous work of Mo’min and friends the cassette would have been lost. Mahmoud Darwish’s involvement as a co-writer on the album would have also been forgotten and with it a wondrously rhythmic example of Palestinian cross-pollination.

These instances of cross-pollination preserve the Palestinian experience post-Nakba and so inform the releases MaJazz Project puts out.

Whether field recordings of the Palestinian Black Panthers jamming in the mountains of Jenin or the label’s upcoming release – a compilation of Kuwait-based Palestinian folk group Al Fajer – MaJazz Project is not only tied to the separation of space and place but how music can provide a glimpse into shared Palestinian consciousness.

So as The New Arab sat down with MaJazz and Al Fajer, the idea that in each cassette reel and crackled vinyl lies not only forgotten Palestinian melodies but the fractured lives of its listeners seemed somewhat appropriate.

A rightful revolution

In an article essentially about the merits of old and new, it was fitting that The New Arab interviewed a 1980s folk band over Zoom.

Now in their 50s, the long-disbanded group were once the darlings of the Palestinian diaspora in Kuwait, with their regional success branching out to festival-packed performances across Europe and the Middle East. “Not bad for a bunch of amateurs,” laughed Jamil Sarraj, the group’s oud player.

Ironically, Al Fajer’s rejection of the then ‘trend’ contributed to their initial success.

At the time of the band’s peak, the late 1980s and early 1990s saw a surge of accessible electronic instruments enter the Arab market.

For Al Fajer – Arabic for The Dawn – such sounds were to be avoided. Each band member cherished the soul of the oud and shebbabeh too much to be enticed by the digital wave, with Al Fajer member Dr Bashar Shammout commenting that “amid such chaotic circumstances, we wanted… and felt people needed… a calming classical influence.”

The circumstances that Bashar alludes to were of course the First Intifada. Sparked by the Israel Army’s murder of four Palestinians in Gaza's Jabaliya refugee camp, the Intifada shook off the shackles that bound Palestinians and sparked a revolutionary mobilisation that would last six years, the ripples of which continue to be felt.

And much like the nida’ – or appeals – of political pamphlets distributed among the streets, musicians and artists alike would galvanise the public in their own way, as Edward Said wrote in Intifada and Independence, to create “a focused will”.

Whether Sliman Mansour’s artistic interpretation of sumud, Naji Al-Ali’s stirring caricatures or Al Fajer’s calming call to endure, each had to role to play.

“When we established the band during the First Intifada there were two streams of music in Palestine and the Palestinian diaspora,” Bashar explained to The New Arab.

“On the one hand, you had the stuff authorised by the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) which was ultra-nationalistic and in your face about revolution and resistance.

“On the other hand, you had bands like us and Sabreen who adopted a different mindset. Our thinking was ‘how can we get our message of a confident Palestinian identity across in a subtle, implicit way?’ You don’t need to be loud to distribute your message, you can avoid the Israeli authorities and stir the audience in your own way.”

One look at Palestinian music today and Al Fajer’s vision seems somewhat prophetic. With time, Palestinian music has evolved from sounding hyper-political to more mundane reflections of daily life. With it, more organic notions of nationhood have emerged.

The legacy then of Al Fajer lies not only in their talent but in the message they carry. Sima Kanaan, Al Fajer's lead singer agreed: “That’s why I think re-issuing our album on MaJazz is so timely. We realised early on that the Palestinian struggle for liberation was also about a global struggle for human rights.

“Our struggle will always be about the land, but the Palestinian narrative today has increasingly shifted towards rights. It’s satisfying to know that our thirty-year-old message continues to resonate.”

A series of unfortunate events

Al Fajer’s perennial messaging and music would take them all over the world, playing to festival goers in their thousands. In particular, their involvement in East Berlin’s 1989 Festival of Political Songs drew special acclaim and is remembered fondly.

“You need to remember; we weren’t professional musicians. Our success was spontaneous. Yet here we were performing in Berlin…it was remarkable really,” said Jamil. “After we performed our song Halalalaya, the 5,000-strong audience shouted ‘Zugabe’ which we figured meant encore.”

Al Fajer’s folk frees us from a modern Palestinian history tainted by Israeli aggression whilst acting as an antidote for Palestinians living under day-to-day occupation"

Bashar also chimed in with an anecdote from the East German festival: “Backstage after our performance, the popular German musician Esther Béjarano came to greet us. She was known as one of the last survivors of Auschwitz and for her involvement in the Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz.

“She loved our performance so much she wanted us to sing together. We agreed but only if she sang in Arabic, so we sat there teaching her a transliteration of our lyrics. That festival and that performance was a special moment for us.”

However, as Palestinians are all too aware, moments of euphoria are often followed by periods of strife. “The fall of the Berlin wall changed everything. One day we were accepted as heroes, the next we were pariahs,” lamented Bashar, who now lectures on cultural heritage in Germany. “East Germany was sympathetic to our struggle and supported us [the Palestinians] with cultural and political funding. Since reunification, the policies of the German Government toward the Palestinians have become very antagonistic.”

Jamil continues. “Then Iraq invaded Kuwait. So in one year, we’d gone from playing festivals to being without a place we could call home.” The two events dealt a hammer blow to Al Fajer and the group disbanded soon after, with the band members now scattered around the world.

In reissuing Al Fajer’s work, MaJazz Project has not only given a new life to their music – dormant now for over 30 years, but to past conditions where Al Fajer’s music had been publicly celebrated.

As Bashar alluded to, Germany today treats Palestinians quite differently. Palestinian memorials and Nakba demonstrations are pre-emptively banned under the pretext of anti-Semitism, and visible symbols of Palestinian identity are routinely targeted. This has led to a consistently hostile environment for Palestinians and their allies.

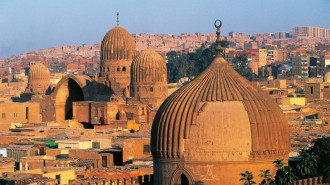

Conversely, Al Fajer’s music gives us an insight into what Kuwait meant for Palestinians during the late 1980s. “It’s very important to mention that Kuwait was an oasis for the Palestinian resistance,” remarked Sima. “The heads of the PLO – including Arafat – used to live in Kuwait, and there were around 400,000 of us living there at the time. It’s important to link our music to this community, people were attached to our music because they were attached to the resistance. In other countries, Jordan for example, this wouldn’t have happened.”

Reissued and reunited

Listening to the album pre-release, it’s no surprise that Al Fajer continues to be flooded with messages. Jamil’s chords have a nostalgic feel that suspends the listener in his grasp, whilst Sima’s vocals both soothe and compel.

What Reynolds’s Retromania, therefore, failed to consider was the possibility that rather than being enslaved by the past, there are certain realities in which it sets you free. The tragedy of Palestine is one of them.

Al Fajer’s folk frees us from a modern Palestinian history tainted by Israeli aggression whilst acting as an antidote for Palestinians living under day-to-day occupation. And it is precisely this message of confident compassion that will scare the Israeli authorities the most. An amateur Palestinian group: a Professor, an HR expert, and a World Bank official has had a lasting positive impact on the national psyche.

Whilst Al Fajer indeed became a victim of their times, MaJazz has breathed new life, and optimism, into the group. “Palestinian music should be given another life,” said Mo’min. “But this time we release it on our terms. We no longer need to explain ourselves; our story is our story.”

Together, they are proof that music is an artform not primarily about social and political authority but a means by which a community can engage itself in a generous, non-coercive and attainable way. And as we’ve learnt from Al Fajer and MaJazz, it is then possible to turn victimhood into celebration.

Benjamin Ashraf is The New Arab's Deputy Features Editor. He is also a Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Jordan's Center for Strategic Studies.

Follow him on Twitter: @ashrafzeneca

![Al-Fajr's spontaneous success is set to be revived once more with MaJazz Project's latest reissue [photo credit: Jamil Saraj]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2022-08/7e0e53f9-fdea-4e15-b3e3-6eb4bc510d0d.jpg?h=f5c6c4a1&itok=GpEBK90t)

![Palestinians mourned the victims of an Israeli strike on Deir al-Balah [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2024-11/GettyImages-2182362043.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=xSHZFbmc)

![The law could be enforced against teachers without prior notice [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2178740715.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=hnqrCS4x)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News