Battling Kuwait's outdated gender roles in Layla AlAmmar's debut novel

Layla AlAmmar's debut novel is set in Kuwait, where the author grew up, and follows Dahlia.

While Dahlia has a job, freely hangs out with her friends at local hotspots and pursues a love of art in her spare time, she is also about to turn 30 and is unmarried – something her mother and society cannot abide. The "veneer of modernity and progressiveness" in Kuwait was something that AlAmmar was keen to explore.

"We have these impressive skyscrapers and all the latest technology and high levels of education, and yet, at the same time, much of the population continues to cling to outdated notions of social interaction and gender relations," says AlAmmar.

"For example, women can vote and run for parliament and be ministers or CEOs of global companies, but they can't move out of the family home unless and until they marry," the author adds.

"A woman can attain the highest level of education, but her signature is not sufficient to authorise surgery for her own child – a male relative must be tracked down to sign off on it. This dichotomised life can create a kind of cognitive dissonance, in some case an almost schizophrenic break, that can have profound effects on a woman's mental health."

|

We have these impressive skyscrapers and all the latest technology and high levels of education, and yet, at the same time, much of the population continues to cling to outdated notions of social interaction and gender relations |  |

This cognitive dissonance is something that comes through in AlAmmar's prose and the way The Pact We Made is structured as well as being explored through the protagonist.

|

|

We learn in fragments about the trauma Dahlia suffered as a teenager, partially because she herself cannot face it and partially because others would prefer her to suppress the trauma for appearances' sake. At times, it seems Dahlia is almost outside of herself or a different person when she is thinking about her trauma.

"I'm fascinated by this notion of 'other selves', and it dovetails well with the 'double consciousness' that exists due to the clash between modernity and tradition," says AlAmmar, "where what people think is often more important than what 'is'."

On top of trying to come to terms with trauma, Dahlia is also trying to work out what it is she really wants compared to what could have been had she made different decisions at earlier points in her life, something she often reflects on.

"A recurrent question in the book is the concept of choices and paths not taken – the idea that we arrive at certain points over and over in our lives where we have to make decisions, and these decisions set us down a path with other decision points," says AlAmmar.

"And so, I'm interested in the exploration of this idea, the 'What ifs?' of other paths, these forks in time, who we might have been – keeping in mind that not choosing is a choice in itself.

"Trauma functions in a similar way. There is a 'before,' an 'after' and the long pause of the traumatic 'present'. There is always the question of what 'before' might have prevented the trauma, what 'after' might have been possible had it not happened, and what choices can be made in the 'present' that could lead to new 'afters'.

"Additionally, when trauma occurs at a young age, it can lead to a wholesale fragmenting of the self, so that the person you might have been is no longer possible."

Dahlia is certainly not the adult she expected to be when she was a teenager, and defining who she is a central preoccupation of the novel, with the subtext often returning again and again to women's roles in Kuwaiti society.

|

A woman is always defined in relation to a man... She's a daughter, a sister, a wife. She's never her own independent person |  |

"A woman is always defined in relation to a man," says AlAmmar. "She's a daughter, a sister, a wife. She's never her own independent person. This is codified in the way she lives at home, under her father's roof and guardianship, before marrying and moving to the home and guardianship of her husband. She's never truly under her own guardianship or seen as a full adult. This can have consequences if and when she marries.

"There is also the notion that a woman is incomplete in some way if she doesn't marry. There is a pervasive idea that this is the primary goal in a young woman's life, and that she is somehow deficient if she reaches a certain age without marrying."

|

|

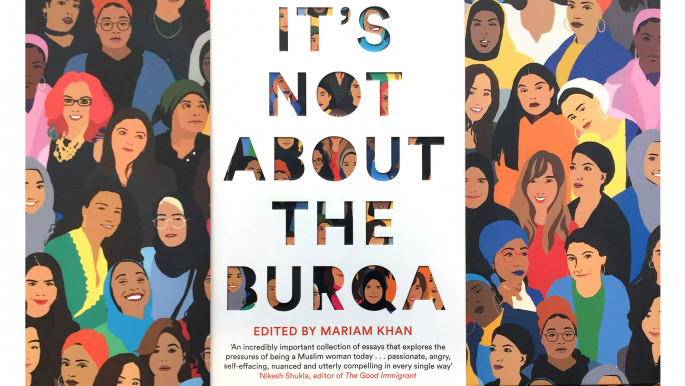

| Read more from The New Arab's Book Club: It's Not About the Burqa: It's about letting Muslim women speak |

AlAmmar talks of the high divorce rate – around 60 percent – in Kuwait, which has come through a loss of stigma around divorce. While it is positive that couples no longer feel the need to stay in unhappy marriages, AlAmmar points out that the loss of stigma has "brought to light fundamental problems with the way in which marriage happens" in Kuwait.

In the novel, Dahlia's two best friends, Mona and Zaina, are both married; Mona found a love match in Rashid, while Zaina, and Dahlia's sister Nadia, opted for an arranged marriage. These marriages, along with others in the book, look one way to Dahlia, but there is more going on beneath the surface.

Indeed, AlAmmar says that Mona and Zaina's marriages "function as examples of… how resistant to easy judgment marriages are".

Also resistant to easy judgement is Dahlia, who is a complex character, unsure of how to navigate a life and roles that have been thrust upon her. But it's no coincidence that she is named after a flower, something that is so easily damaged but that, with some care and attention, the right kind of light and tenderness, can be restored to something newer and stronger.

In Dahlia and The Pact We Made, AlAmmar has created something strong and lasting, a book about a woman battling to exist on her own terms in a world which wants women to stay quiet. Dahlia and AlAmmar are making their voices heard, and that's a great thing.

Order your copy of The Pact We Made here.

Sarah Shaffi is a freelance literary journalist and editor. She writes about books for Stylist Magazine online and is books editor at Phoenix Magazine. She is a judge for the Jhalak Prize 2019. Sarah is editor-at-large at independent children's publisher Little Tiger Group. She regularly chairs author events, and is co-founder of BAME in Publishing, a networking group for people of colour in publishing.

Follow her on Twitter: @sarahshaffi

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News