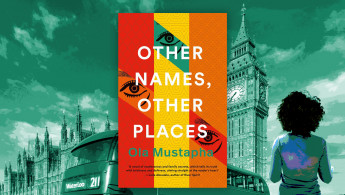

Other Names, Other Places: Codeswitching will take its toll

As the daughter of a North African Arab immigrant to London, I have multiple names. Officially I am known as Yousra, to my family I am known fondly as Susu, I am Yuss to friends and acquaintances who can’t quite pronounce my name, and in Starbucks – well in Starbucks I don’t even bother, I tell the barista that my name is Sarah.

This idea of using different monikers for different people – a type of name codeswitching - is shared by the protagonist in British Egyptian author and writer Ola Mustapha’s debut novel, Other Names, Other Places which was published in July.

Other Names, Other Places is told from the point-of-view of Nesrine, the daughter of Tunisian immigrants to London. Officially her name is Nesrine, while she is Susu to her family and Nessie to everyone else.

"Do people from majority cultures feel our pressure or do they just have a blank slate to write whatever they want"

Nesrine arrives to London in 1979 as a three-year-old with her older sister Sherine and her mother, to reunite with her father who immigrated some years prior to them.

Her father runs a business selling imported goods from the Middle East on Edgware Road, a location infamous for being the hub for London’s Arab community. Nesrine’s parents befriend an English woman, a librarian called Mrs Brown, who plays a pivotal role in their lives: on the face of things, she is a friend to her father, confidante to her mother and somewhat of a carer to Nesrine and her sister.

What unfolds is a story of family secrets – one day Mrs Brown disappears from their lives and Nesrine spends the rest of her life trying to figure out why. Her perception of her parents is shaped by two disturbing incidents she witnessed as a child and through the novel, we learn how the reality of things can be very different to what we perceived them to be as children. When Mrs Brown re-enters Nesrine’s life when the latter is an adult, she is on her death bed, asking Nesrine to recount childhood memories. Nesrine finally has the opportunity to dig deeper into those family secrets.

As a British Egyptian Muslim reader, coming across this friendship of Muslim Arab parents to a white, non-Muslim English woman is somewhat of a surprise. Why didn’t Mustapha write a book about immigrant family dynamics and family secrets without this English woman? But it is all for good reason.

“Mrs Brown is the link between Nesrine’s family and British culture, and because of that they all depend on her in different ways,” Mustapha explains to The New Arab. “For the two girls, she provides a gateway to normality. She takes them out and she gets them to do all these things that their parents probably wouldn't get them to do. To the mother, she's a support who helps her get out into the world. To the father, she provides status in a way — a link to this English society that he's never really going to be part of. But then there's a bigger question of what she was getting out of it. And I wanted that dynamic, this kind of mutual need, though it's not completely obvious why they all need each other.”

|

Growing up in ‘80s North London, Nesrine, Sherine and her parents are part of a small pocket of North African immigrants who haven’t quite “assimilated” into British society (I’m using the term assimilation as meant by those in the British government who are obsessed with the idea of integration - giving up your ethnic customs and heritage).

They are quite an isolated Tunisian family and as is the story of many second-generation immigration children in Britain, Nesrine and her sister Sherine spend years trying to determine their racial identity. Sherine tries to be as “English” as she can, while Nesrine is a bit of a floater, identifying as North African but not fitting in with the children of other African immigrants at school, nor fitting in with the white English children either.

Nesrine’s questions about her racial identity are something that resonates with author Ola Mustapha, who is the daughter of Egyptian immigrants to London. Mustapha grew up in ‘80s and ‘90s London and while that helped inform the socio-economic context of the novel, she wants to make it clear that this is not a semi-autobiography, which is also part of the reason why she decided Nesrine and her family would be Tunisian and not Egyptian.

“I did want to write about someone from a North African background, but I deliberately didn't make the family Egyptian because I had a feeling that if I made them Egyptian, intentionally or not, I would end up writing about myself and my own family,” says Mustapha. “So, I wanted a little distance. The other reason why I chose a Tunisian family was because the French language plays a role in the book, so I wanted the family to be from a culture where French is spoken by some people.”

“The other thing was it was a time when there were few young Tunisian people in England and I wanted the family to be isolated, even within the Arab community, because most Tunisian people would go to France rather than England.”

Nesrine’s father is never referred to as her father or Baba, but crudely as 'That Man'. What is portrayed is a dysfunctional family dynamic that some children of immigrants may be familiar with – a hardworking but overbearing, highly critical and controlling father and a somewhat passive and depressed mother who struggles to acclimatize to this new country which has been thrust upon her.

However, the character of Nesrine’s father is not without context. Towards the end of the novel Mustapha manages to get the reader to feel sympathetic towards him.

“I never wanted him to be a monster because he's not,” says Mustapha. “I wanted to make the point that he was suffering too, and more broadly, even though there is that archetype of the overbearing Arab father, they are also suffering. When you have these unequal power structures, we all become victims. I didn't want him to be an absolute caricature who had no redeeming features, and I wanted that to come through in the way that the two girls, as they grow older, begin to appreciate that a lot of his flaws just stem from his frailties and the obstacles that he himself faced and that he was a victim too. He wasn't just the perpetrator of all the stuff that hurt them.”

|

As adults, the moment they are able to, Sherine and Nesrine leave home.

When Nesrine emigrates to Japan it is on the premise that she is going out there for work; her father constantly asks her when she will return home.

While Sherine makes it clear she left home because of him, Nesrine appears to have more feelings towards her father and refuses to tell him the truth – the truth being, she hasn’t emigrated to Japan purely for a job but to put distance between herself and him. By this point, her mother has returned to Tunisia – on her own.

In many novels that examine the experience of Arab immigrant families in the West, there is inevitably always a child or two (in this case both Nesrine and Sherine) who long to be more like the dominant host culture – to be more English.

This is only natural in countries where the state and mainstream media make us feel unwelcome unless we “integrate” and demonize our parents for not doing so. But interestingly, towards the end of the novel, although Nesrine and Sherine don’t come entirely full circle, they definitely start appreciating their Tunisian roots.

“Nesrine definitely has a bit more appreciation than Sherine of what it's like to leave your country and move to another one. And I think having been a foreigner in a different place [Japan] made her appreciate her parents. She did come to appreciate her Tunisian-ness as some sort of grounding force. You can leave your family behind, you can go as far away as possible from them, but then you might start to feel like something's missing if you completely separate yourself. I think that was definitely part of her trajectory.”

As an adult, Nesrine evolves into a flawed character who struggles with monogamy and hurts others with her infidelities. She does other things that are considered taboo for an Arab and Muslim woman such as drinking alcohol and clubbing. With the ever-present question of representation lingering over female Muslim authors, I ask Mustapha whether she felt any pressure to write her Muslim and Arab female protagonist in a certain way.

“When you start writing the character you have a vague idea of what they're going to be like, but then they really do take on a life of their own. I found Nesrine becoming much more dislikeable than I originally intended,” reveals Mustapha. “As I went on with the writing process, I wanted her to be someone who does all the horrible stuff that maybe most people would restrain themselves from doing, but at the same time, she's not a complete psychopath. She's got a conscience. She just doesn't have the self-control to stop herself.”

“It's a really interesting question about the burden of responsibility that we might feel, and how it influences the kind of characters we write. Do people from majority cultures feel our pressure or do they just have a blank slate to write whatever they want? You could say Nessie’s really flawed, she's not typical. She's maybe deliberately outrageous, but even if she's one in a million, why shouldn't we write that? A one-in-a-million character.”

Yousra Samir Imran is a British Egyptian writer and author who is based in Yorkshire. She is the author of Hijab and Red Lipstick, published by Hashtag Press

Follow her on Twitter: @UNDERYOURABAYA

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News