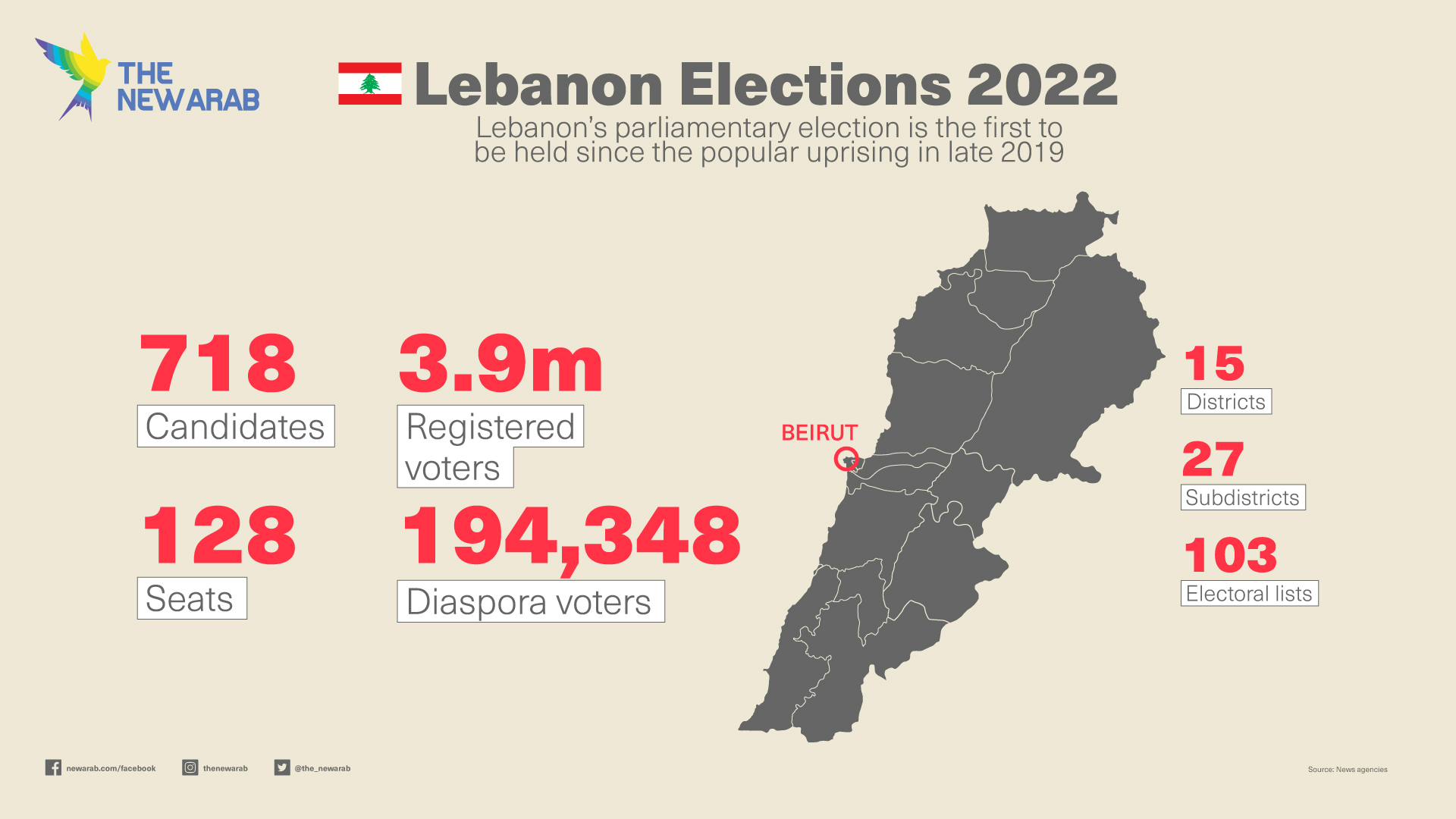

Welcome to The New Arab’s coverage of Lebanon’s General Election 2022 held on May 15, 2022. Follow live updates, results, analyses, and opinion in our special hub here.

Abdulrahman Kaskass’s shop is empty as he speaks. The watches, accessories and jewellery he imports for his customers have stayed put on his shelf for far longer than he would have liked.

“People don’t buy watches when they are barely able to afford food,” the 30-year old shopkeeper tells The New Arab.

His business, like the rest of Lebanon, has suffered deeply as the country has plunged deeper into crisis. The economic crisis has thrust over two-thirds of the population into poverty, produced dire shortages in medicine and deprived much of the population of basic services, such as electricity.

"People don’t buy watches when they are barely able to afford food"

On Sunday, the country goes to vote in its first parliamentary elections since the economic crisis began in 2019. The depths of the crisis and the remnants of optimism from Lebanon’s October 2019 revolution, when millions took to the street in protest of corruption, have led to an explosion of independent candidates.

Whether these independent candidates will win seats depends on if Lebanese are willing to deviate from the traditional sectarian parties that have dominated the political scene for decades. And if people actually show up to vote.

Young voters like Kassas could play a large role in this election, as they have been among the loudest voices in support of independent candidates and reforms since the economic crisis started.

"While he does not yet know who he will vote for... he is determined not to vote for the same politicians who he says brought the country to its knees"

“We are not going to vote for the appropriate person. They have to make a change for us, get us food and water, and help us secure the basics of life. This is how we’ll vote,” Kaskass said from his shop in Corniche al-Mazraa, a busy commercial street in the heart of Beirut.

He adds that while he does not yet know who he will vote for – the election is in two days – he is determined not to vote for the same politicians who he says brought the country to its knees.

“The biggest mistake people make is being loyal to their Za3im [a local political patron]. The Za3im is the one who made me hungry. And then when he wants me to vote for him, he sends me a box of food. What do I want a box of food for when you’re the one who made me hungry in the first place?” Kaskass said.

This will be the second parliamentary election he will vote in – and the stakes are perhaps higher than ever.

A new generation of voters

Kassas, like many of Lebanon’s youth who are going to the polls for the first time, are in a unique position.

They do not have the political baggage of their parent's generation. The scars of the civil war and its sectarian bloodshed, while visible on the edifices of the buildings they live in, do not weigh as heavy on their minds.

The most formative experiences of their political lives are not the expulsion of Israeli and Syrian forces from Lebanon, but an internal battle against the corrupt cronies who have ruled their whole lives.

It was not an external enemy who blew up the Beirut port, but rather the negligence of their own government.

“The young generation is more willing to give independents a chance than the older generations who are more attached to nostalgia or the war. The new generation is more willing to actually change,” Charbel Chaaya, a 21-year-old activist with the Mada secular student youth network, told The New Arab.

Chaaya’s political priorities – quality education, healthcare and a way of stopping the accelerating emigration of his peers – are all forward-thinking. They also far outstrip the abilities of Lebanon, which has been described as a “failed state” and is unable of providing its citizens with more than two hours of electricity a day.

"I don’t think elections can lead to radical change. But they are essential because along the way you can push your agenda and speech"

He is also aware that even in the best-case scenario, Sunday’s vote will not lead to an immediate change.

“I don’t think elections can lead to radical change. But they are essential because along the way you can push your agenda and speech. This is the importance of elections, to get more involved and convince more people to further the project,” Chaaya said.

He continued that while he thinks young people are eager for a change, most have not educated themselves enough on how to do so. His inbox was filled with messages from his friends in the days coming up to the election; they were all asking him who they should vote for.

“Some people are going to vote just to punish the system. But they do not have much exposure to politics or have an idea of who the candidates or lists are,” Chayaa said.

Preventing youth apathy

Yasmina Farkh, a 24-year-old Lebanese graduate student at the London School of Economics and Political Science, was also afraid that her peers would be apathetic in the upcoming election.

She took to social media to express her thoughts, writing an article outlining her thoughts on the duties and responsibilities of Lebanon’s youth to vote in the upcoming election.

“It’s important for the youth to vote because this is one of the main ways we can secure a future worthy of our potential. We’d be betraying that potential should we decide to abstain from voting,” Farkh told The New Arab.

She added that she deemed it her “duty” to vote the current establishment out and vote for the alternative candidates.

"It’s important for the youth to vote because this is one of the main ways we can secure a future worthy of our potential. We’d be betraying that potential should we decide to abstain from voting"

If the over 60% voter participation rate from the Lebanese diaspora is any indication, this election will see many more come out to vote than in 2018. It remains to be seen if this will translate to youth participation.

For her part, Farkh is cautiously optimistic about Sunday’s election.

“A big percentage is thirsty for change and is luckily finally eligible to vote. So much has happened since the last election, and the youth is wary of it,” she said.

Should that change not come, however, it could be the last straw for many young people in Lebanon.

“If there’s no change in this country, I will go to any country that will take me. And when I get residency there, I will also vote. But from abroad,” Kaskass said.

William Christou is The New Arab's Levantine correspondent, covering the politics of the Levant and the Mediterranean. William is also a researcher with the Orient Policy Center. Previously, he worked as a journalist with Syria Direct in Amman, Jordan.

Follow him on Twitter: @will_christou

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News