Lebanon's Anti-Racism Movement is a lifeline for vulnerable migrant workers during coronavirus

The coronavirus pandemic is the latest in a string of calamities to hit migrant workers in Lebanon, where a protest movement started last year against corruption and a financial crisis.

As of April, nation-wide protests have erupted again, defying a state-mandated ban on large public gatherings as Lebanon grapples with its worst economic crisis since the 1975 civil war ended three decades ago, in tandem with a coronavirus outbreak.

According to the Health Ministry's live toll, Lebanon has recorded 725 coronavirus cases and 24 deaths resulting from infection since the first case was confirmed in February.

The spread of the virus to Lebanon and the preceding economic crisis – now characterised by an all-time-high currency depreciation and a shortage of hard currency – has hit some 250,000 migrant workers employed in Lebanon especially hard.

The Anti-Racism Movement (ARM), a Lebanese NGO, has become a lifeline for cash-strapped migrant workers otherwise left to fend for themselves after losing their livelihoods while stranded in Lebanon.

Migrants bearing the brunt

Excluded from national labour laws and granted little to no protection under Lebanon's infamous 'Kafala' employment system for foreign workers, migrant workers – most working in different domestic housekeeping jobs – are left particularly vulnerable in the face of crises like the coronavirus pandemic.

With the emergence of the economic crisis in 2019, employers already started slashing monthly salaries of domestic workers or paying them in devalued Lebanese pounds despite initial payment agreements in USD, citing the economic falloff and banking crisis. Some employers have stopped paying wages entirely, according to workers.

|

|

Artwork by Sandy Lyen [Anti-Racism Movement]

|

With the Lebanese government sitting idly, the ARM – now active for a decade – has become the last line of defence for thousands of migrant workers.

The ARM has swept in as a first responder, delivering aid boxes to workers who have run out of cash for food and necessities, and advocating to protect migrant tenants, after conducting its own rapid needs assessment in mid-April.

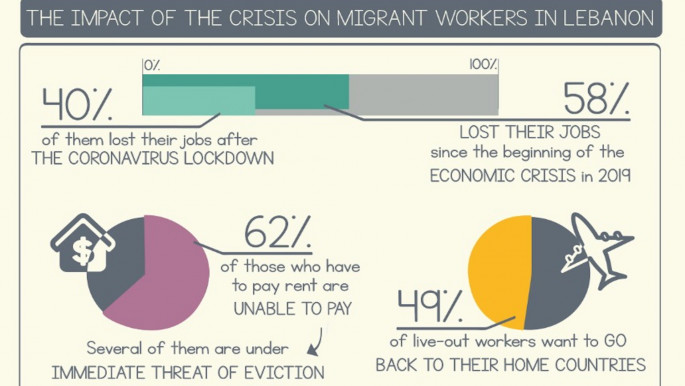

In its survey, ARM found 40 percent of migrant workers had lost their jobs after the coronavirus outbreak, while another 18 percent were laid off since the start of the financial crisis.

However, the survey could not include in-house domestic workers not allowed access to phones or internet by their employers, in addition to workers who could not afford the services.

Another half of migrant workers in living arrangements separate from their employers said they had limited to no access to food, according to the data compiled by ARM.

An unprecedented need

"The needs [of migrants] have increased and changed dramatically since the beginning of the crisis and now with the coronavirus lockdown. We're seeing a lot of people request food or water," Zeina Ammar, ARM Advocacy and Communications Manager, told The New Arab.

The non-partisan movement, which mainly combats racist discrimination and abuse in Lebanon against migrant workers – mainly domestic workers – their children, as well as Sudanese refugees, has had to focus its efforts on a new front to meet the needs for rapid food and housing assistance.

"Our priorities and interventions have shifted considerably since the beginning of the crisis in 2019. The classes given at the Migrant Community Centers have moved online. We are also faced with very high demand for basic necessities among migrant communities so we had to step in to respond to those emerging needs."

|

|

Excerpt of infographic [Anti-Racism Movement / Sandy Lyen]

|

On a legal front, the movement is pressing officials for emergency legislation that would grant a grace period for rent to protect migrant tenants.

"Together with the Housing Monitor and 10 other groups and organisations, We sent a letter to the Ministries of Interior, Justice and Social Affairs, as well as the Prime Minister's office urging them to prohibit evictions at this time," Ammar said.

For food needs, the ARM is also cooperating with the local non-profit People's Solidarity to document needs and collect donations.

Donation boxes are planned to assist over 2,000 families for half a year, and potentially more if further donations are secured, Ammar said.

"We have a big team, and we're trying to divide and conquer because there is too much to do. We issued a call for volunteers and we hope to find the help we need to cover the needs on the ground," Ammar said figuratively, highlighting the overwhelming need.

|

Our priorities and interventions have shifted considerably since the beginning of the crisis in 2019 |  |

While the distribution of basic necessities tends to the more rapid need, the NGO is advocating in parallel for the inclusion of workers in the national Covid-19 response plan and long-term solutions for migrants, such as integration in the national Labour Law, Ammar said.

ARM, which directly consults and cooperates with local migrant workers is a long-standing critic of the Kafala system, calling for its abolition. The system has also been condemned by international rights groups, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, for putting workers at risk of exploitation and abuse.

In-depth: Trapped in Lebanon: Fears of abuse for migrant domestic workers amid Covid-19 lockdown

The Kafala – or sponsorship – system legally binds the worker's residence in the country to their employer. It also traps workers in contracts that can only be terminated with the consent of employers, who often require compensation as penalty, even in the case of abuse or non-payment of salary.

With Lebanon now seemingly slated for further economic deterioration due to the coronavirus pandemic, many migrant workers have expressed an urgent need to return to their countries over fears of starvation and further abuse.

A race against time

In the ARM survey, nearly half of 319 migrant workers who do not live with their employers said they wanted to return to their countries.

Claiming that the closure of the Beirut airport has blocked access to foreign currency, Lebanon's banks have suspended US dollar withdrawals, ensuing further evaporation of liquidity and a ban on foreign transfers – to the detriment of domestic workers who rely on foreign currency to support their families back home.

On top of the inability to support families back home, migrant workers in Lebanon are now scared of going hungry themselves.

|

We urge employers to compensate freelance domestic workers for the shifts that they are forced to miss due to the lockdown measures. For many families, this is their only source of income |  |

For freelance domestic workers, the flow of work has slowed exponentially with the spread.

"Families are self-isolating so they don't want anyone to come to their homes, which is understandable, but we urge employers to compensate freelance domestic workers for the shifts that they are forced to miss due to the lockdown measures. For many families, this is their only source of income," Ammar said.

The ARM has deployed its workers, as well as volunteers, in the field and on phone operations in a recent campaign, to reach what it said is an unprecedented need for full-force assistance on all fronts.

"It's really a solidarity campaign with migrant workers. We have a budget to assist 2,200 families for about 6 months. The numbers might decrease because the prices are increasing every day but we are trying to secure more funding," Ammar said.

With the currency in freefall and further inflation impending, the ARM is in a race against time to meet the needs of workers. Donations, especially those made in hard currency channelled from abroad, might be the key to reach the workers in time.

"The box we're packing now, the box that contains the basics, is getting more expensive because of inflation," Ammar added.

A milestone in migrant rights advocacy

The ARM was launched in 2010 as an initiative by a group of young Lebanese women's rights activists in collaboration with migrant workers – specifically domestic workers.

Two years later, ARM registered their NGO and hired staff after a video it released of a racist incident caught on tape by its activists went viral, highlighting Lebanon's alarming institutionalised and social racism.

|

ARM activists at the time summoned the police, and questioned, in the officer's presence, the admissions employee, who said workers were only allowed in if they were in the company of their employers – shedding light on the toxicity of the employer-employee relationship under Lebanon's Kafala system.

The video depicted a migrant worker being denied entry to a private beach resort in Beirut under the guise of 'membership only' access, while a Lebanese person was allowed to go in without a membership.

Since then, ARM has been advocating against the Kafala system and discrimination. The ARM's largest project, the Migrant Community Centers (MCCs), has expanded to two major cities from the Beirut centre opened in 2011, and an additional educational space was launched, operating on Sundays – the only day some migrant workers are allowed to leave their employer's homes.

"It's a community space that migrant workers can use by paying a symbolic membership fee on a yearly basis. The centres host events, birthdays, language classes and capacity building workshops," Ammar said. "It is closed now due to the coronavirus".

The centres, where members could also cook, do laundry and organise activism events, closed on 11 March as a coronavirus precautionary measure. But most migrant workers now are more worried about their immediate survival.

Gasia Ohanes is a journalist with The New Arab.

Follow her on Twitter: @GasiaOhanes

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News