The Lebanese board game fighting corruption with humour

After weeks of sitting at home, depression started to creep in. That's when Elie Kesrouany knew it was time to do something.

Covid-19 had brought normality to a halt: his board game shop was closed, and his financial situation was getting more and more precarious.

Projects to facilitate online games, or selling his board games on Instagram, were crushed by the worsening economic situation in Lebanon. "The inflation of the dollar forced me to think different," he told The New Arab.

So, he decided to develop a game in order to survive, and to bring some lightness to people's homes. "I wanted to make people laugh but think about really important things at the same time," he tells The New Arab. Calling it "Wasta", he knew he was going to hit a nerve.

"Our country is full of Wasta - it's full of corrupt people who are in the wrong positions because of it," says the 37-year-old. He is a big man with a kind voice, wearing shorts and crocs for comfort in the unbearable late summer heat.

Kesrouany just finished reorganising the 150 games in his store "on Board", just outside of Beirut, to get ready it for the post-Covid-19 reopening. Sitting on one of the outside tables, he is sipping fresh pomegranate juice, his favourite.

|

Our country is full of Wasta - it's full of corrupt people who are in the wrong positions because of it |  |

Loosely translating into "nepotism", Wasta is a heavily loaded term in Lebanon and the Arab world, expressing the use of connections in order to get somewhere.

|

|

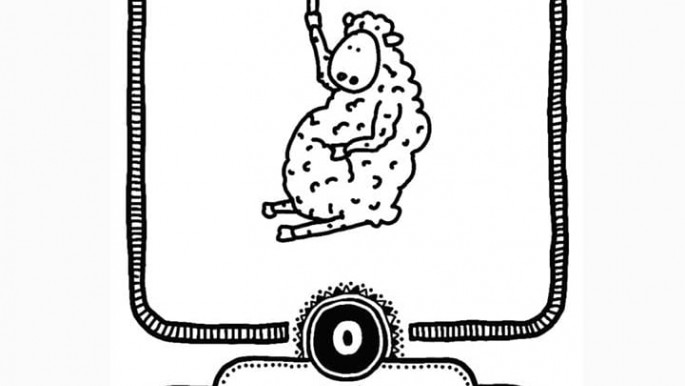

| The Sheep: Players choose someone and they become your warlord - represents those who follow blindly |

"People use their family or social contacts to skip the line and gain quicker and better access to schools, universities, hospitals or jobs," noted Transparency International in a comment titled: "Wasta: How personal connections are denying citizens opportunities and basic services", last year. According to the organisation, "65 per cent of citizens (in Lebanon) used Wasta when dealing with the courts."

The word has become synonymous with widespread corruption in Lebanon, which is going through the worst economic crisis since the end of the civil war in 1990. The Pound has lost 80 percent of its value; the garbage, sewage, water and electricity systems are strained. Restrictions imposed due to Covid-19 put even more pressure on the already fragile country.

"Wasta is a sarcastic way to criticise the Lebanese society and all the wrong things that are happening," says Kesrouany. He chuckles: "I don't know how to say it in a more polite way". His vision was to create community among young people, who find themselves angry and lost.

For illustrations, Kesrouany approached Bernard Hage aka "the Art of Boo", a well-known political caricaturist in Lebanon. The idea of Wasta immediately resonated with Hage, who, at the time, also found himself "in the middle of a lockdown downness".

"Humour is more powerful than other outlets, because people just want to laugh," he says. His satirical cartoons appear in the French Lebanese Daily newspaper L'Orient du Jour.

|

Humour is more powerful than other outlets, because people just want to laugh |  |

Not everyone was happy when 'Wasta' was released, as it alludes to almost every player in the country's political landscape caricaturing the many ailments of a broken political system. "There were calls," says Kesrouany. They ignored them.

|

|

|

The Thug: Players drop their card and draw a new |

Anticipating unfavourable reactions, the duo outplayed critics by working with symbols rather than naming specific parties or personas. "I really know where I am living, my feet are on the ground, so I know how to deliver my message within the lines," says Hage.

He too, is tired. "I wish I could practice full freedom of speech and just say: F**k you Mr. President."

Carmen Geha, Associate Professor for Political Studies at AUB works with young people every day and has been observing their struggle. "It is sad that this generation has to think about things they shouldn't be thinking about," she says, "they google how ammonium nitrate can be detected in the air, and instead of building board games to save the planet they make board games on Wasta."

In October 2019, the month a tax on WhatsApp was imposed and the economy started to implode, young people went to the streets and declared the "thawra" - the revolution.

"Since October 17 we have a public opinion protesting against the ruling class, this is a cornerstone," says political scientist Jamil Mouawad. The challenge is that "we need to transform this action into political opposition which will take time. For now, Lebanese civil society expresses itself in non-organised opposition, like aid, arts, music, films, and games.

Kesrouany opened his board game shop in December 2019, in the height of the revolution. "It went well, you wouldn't believe", he recalls, still startled by the success despite the economic crisis. A possible reason is that the shop is more than a place where people can buy games. He wanted to "get people together, have fun aspect and give people an alternative to always talking about politics", at least not directly.

|

It hit me this year after the revolution started: I never had one day of normal life |  |

2020 was rough. The ongoing economic crisis, Covid-19, the power cuts - "things were bad", he says. And then came 7 August. When a massive explosion rocked Beirut's port and destroyed large parts of the city, leaving more than 200 dead, 6,000 injured and hundreds of thousands without homes, something has shifted in the psyche of the population. For many Lebanese, it was the tip of the iceberg.

|

|

|

The Neighbour: Players can look at someone else's |

"We are witnessing a total collapse", says Kesrouany. The youth is angry. "But anger is better than helplessness because it gives you agency." Having said that, he admits that since the explosion, he reached a point where he started to feel numb.

He is not alone. Says Hage: "It hit me this year after the revolution started: I never had one day of normal life", says Hage. "There is always protesting, there is a lack of water, a lack of electricity, lack of public spaces".

Now, like many Lebanese both Hage and Kesrouany are getting ready to leave the country. Kesrouany wants to pursue his dream of spreading the concept of his board game shop, and Hage just wants to remember what a quiet Sunday afternoon feels like. But they are torn. Hope and the love for their country are difficult to ignore.

The most important card of Wasta is the Lebanese flag. "If you throw it, you play your most valuable asset: you leave the country and you lose the game," says Kesrouany. The flag symbolises the incorruptible sense of pride and hope among Lebanese people.

In the end, the love for Lebanon outweighs all the evil forces, including Wasta, the card which, when played, can take the shape of any other card. The flag beats Wasta, at least in the game.

Victoria Schneider is a freelance writer reporting from the Middle East and Subsaharan Africa. She was a fellow of the Tow Knight Center for Entrepreneurial Journalism in New York and has published with Al Jazeera, Guardian, and many others.

Follow her on Twitter: @vic_schneider

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News