Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage: A beautifully illustrated book to better understand the solemn journey

The Hajj – the pilgrimage to Mecca and the procession of prayer and exertion – is central to a Muslim’s imagination of their faith. Yet, most Muslims will never perform the Hajj.

Unlike the other four Pillars of Islam, Hajj is conditional on one’s health and means. Thus, Muslims often experience Hajj indirectly via stories, photographs, images, and artefacts.

This performance and representation of Hajj are beautifully brought to life in Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage by Qaisra M. Khan, a lucid history told in narrative and art.

The artwork belongs to British-Iranian collector and professor Sir Nasser David Khalili.

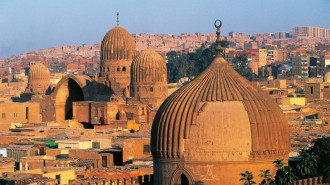

No other destination in the world serves a role comparable to Mecca – a city drawing millions every year from every concern of the world in a performance of faith.

And the Hajj – men and women of every creed and class adorned in white sheets – evokes the essence of faith: equality before God.

This global rotation around Mecca is made tangible in artefacts that pilgrimages carried along or brought back, such as 19th-century Chinese porcelain Zamzam water mugs or Egyptian embroidered cloth. And in the train and boat tickets that are also shared by Khan.

One ocean liner carried passengers from Singapore to Jeddah. In 1800, Joseph Conrad wrote about the real-life, Hajj-bound SS Jeddah.

"For Muslims who have not experienced Hajj and for non-Muslims, Khan’s Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage is a beautifully illustrated journey toward better understanding this solemn pilgrimage in many dimensions"

Khan features a 1901 image, originally published in a French magazine, of Turkish pilgrims praying on a steamship.

The Ottoman Empire attempted to reduce travel time via the Hijaz railway of Lawrence of Arabia fame. The train tracks were sabotaged during the First World War by Arab rebels seeking to overthrow Turkish rule.

The Hajj factored in colonial and post-colonial governance in Southeast Asia. British-ruled India considered the pilgrimage an indulgence and forced upon Muslim subjects the humiliation of seeking permission to perform an act of faith. Pakistan’s post-partition government printed a Hajj-exclusive bank note to be exchanged in Saudi Arabia.

The tradition of Muslim paintings of the Kaaba and ritual objects offered those Muslims unable to perform Hajj the opportunity to bear witness to the pilgrimage.

Alongside the Kaaba drapes, the artistry of the Hajj was most notably exemplified by a palanquin, known as mahmal. In a tradition inaugurated by the Egyptian Mamluks and continued by the Ottomans, this square-bottom, triangle-top structure was adorned in lavish and colourful cloth.

"Hajj is for Muslims, but Western fascination dates back centuries. Today, Saudi Arabia’s conservative interpretation of Islam means that non-Muslims cannot visit Mecca but entering the holy city was a lot easier centuries ago"

A mahmal represented the sultan’s sovereignty over the holy sites and carried gifts, coins, and textiles to Mecca.

Hajj is for Muslims, but Western fascination dates back centuries. Today, Saudi Arabia’s conservative interpretation of Islam means that non-Muslims cannot visit Mecca but entering the holy city was a lot easier centuries ago.

“In another part of the said temple [Mecca] is an enclosed space in which there are two live unicorns, and these are shown as very remarkable objects, which they certainly are,” wrote the Italian traveller Ludovico di Varthema, believed to be the first European to visit Mecca in 1503.

Ludovico’s unicorn tale illustrates how European travel diaries drifted into Orientalist fantasy and myth. In the 16-17th centuries, European visitors erroneously wrote that the Prophet Muhammed was buried in Mecca (and his tomb was suspended in mid-air via magnets) and related Islam to idolatry.

Western accounts took on a more factual approach starting in the 1800s. The British explorer Richard F. Burton’s The Guide Book: A Pictorial Guide to Mecca and Medina (1865) was an accurate account of his journey to Mecca that was also widely acclaimed in its time.

Even in sombre accounts, however, myths still proliferated until the 20th century. Europeans did not simply write about Mecca, they also drew and sketched the city’s mosque and environs – including the first known map of the Arabian Peninsula crafted in 1548 by Giacomo Gastaldi.

A fin de siècle Victorian miniature theatre set features The Kaaba and Kissing-Stone, Mecca alongside the Kremlin and the Statue of Liberty in a collection of world-famous monuments. Mecca plays a role in a learning game for children printed in London in 1816.

For Muslims who have not experienced Hajj and for non-Muslims, Khan’s Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage is a beautifully illustrated journey toward better understanding this solemn pilgrimage in many dimensions. His concise chapters paired with 300 illustrations are a triumph.

Khelil Bouarrouj is a Washington, DC-based writer and civil rights advocate. His work can be found in the Washington Blade, Palestine Square, and other publications

![Palestinians mourned the victims of an Israeli strike on Deir al-Balah [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2024-11/GettyImages-2182362043.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=xSHZFbmc)

![The law could be enforced against teachers without prior notice [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2178740715.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=hnqrCS4x)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News