Oil turning to tears: Climate-induced droughts are drying up MENA's olive oil production

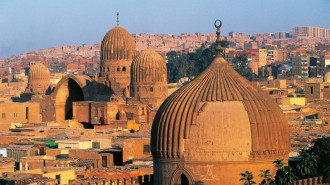

To tackle the spectre of global warming, the United Nations has convened the 2022 UN Climate Change Conference in the Red Sea resort town of Sharm El Sheikh.

As activists, scientists, and diplomats across the globe gather in Egypt for a meeting better known as “COP27,” another international organisation is debating an environmental issue with implications for North Africa’s economies as well as breakfasts, lunches, and dinners the world over: how will global warming affect the production of olive oil?

The International Olive Council (IOC), which defines itself as the “only international intergovernmental organisation in the field of olive oil and table olives,” represents the world’s largest producers of olive oil. IOC member states include most of North Africa – Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia.

Climate change portends devastation for agriculture in all five countries, threatening the future of a favoured ingredient in Mediterranean kitchens.

"Increased temperature has contributed to a 34% reduction in agricultural productivity growth in Africa since 1961"

A recent report on climate change by the World Meteorological Organization found that “the warming has been more rapid in Africa than the global average,” adding that “increased temperature has contributed to a 34% reduction in agricultural productivity growth in Africa since 1961,” a greater drop “than any other region in the world.”

In an ominous note, the report also observed that “the warming trend for North Africa, around 0.41 °C/decade between 1991 and 2021, was higher than the warming trend for all the other African sub-regions.”

Heat waves pose a serious risk to the production of olive oil in North Africa, which accounts for much of the world’s supply. According to provisional data from the IOC, Morocco produced 160,000 metric tons of olive oil between October 1, 2020, and September 30, 2021, making that country the world’s fifth-biggest producer.

Tunisia, the world’s sixth-largest producer during that period, recorded 140,000 metric tons. Algeria and Egypt together had 100,000 metric tons.

It appears that climate change has already begun to impact the productive capacity of IOC member states. While the IOC estimated last November that Morocco’s yield of olive oil would reach 200 metric tons in the 2021-2022 season – a jump of 25 percent from the previous period – a severe drought led the Moroccan trade association Interprolive in September to predict “quite low” harvests.

The Tunisian National Olive Oil Board, meanwhile, anticipates a 15 percent dip in Tunisia’s production in the 2022-2023 season, due to the country’s own drought.

With climate change becoming a more persistent aspect of everyday life, the consequences for olive oil look set to grow worse.

The Tunisian National Observatory for Agriculture predicts that Tunisia’s production of olive oil may drop 35 percent from its 1981-2010 average by 2050 and 70 percent from that average by the turn of the century. Production in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, and Morocco seems unlikely to fare much better in the face of global warming.

The IOC’s mission statement describes the international organisation as “a decisive player in contributing to the sustainable and responsible development of olive growing” that “serves as a world forum for discussing policymaking issues and tackling present and future challenges.”

Given that few issues represent a greater challenge for producers of olive oil than global warming, the IOC appears well-positioned to support an approach to climate change mitigation that promotes sustainable agriculture and emphasises measures to protect North Africa’s olives.

This year, the IOC has taken a few steps in the direction of encouraging climate change mitigation. In May, the IOC held a meeting with officials from the University of Jaén in Spain to discuss what an IOC press release called “the fight against climate change in the olive sector.”

In September, the IOC then hosted an “international workshop” on “olive resilience to climate change” in Portugal and an online “advanced course” on “olive growing and climate change.”

The IOC’s initiatives can help North Africa’s farmers develop techniques for climate change mitigation. However, a long-term solution to global warming’s impact on olive oil will likely require a combination of climate finance and greater involvement from the international community.

As the host of COP27, Egypt might highlight to a global audience how climate change has affected its and other countries’ production of olive oil, a commodity whose economic and agricultural significance stretches beyond North Africa.

Several Arab countries in the Middle East have their own stake in the market for olive oil. Jordan and Lebanon, both IOC member states, together produced about 50,000 metric tons of olive oil in the 2020-2021 season.

Despite a decade-long civil war, Syria recorded production of 115,000 metric tons during that period. Even Saudi Arabia, a country better known for deserts than farms, managed to eke out 3,000 metric tons of olive oil in the 2020-2021 season.

The ability of budding producers like Saudi Arabia to grow their exports of olive oil will depend on the international community’s willingness to confront climate change.

A sharp dip in the production of Morocco, Tunisia, or another leading exporter could likewise reverberate through the industry, clouding the future of one of the world’s most important food staples. Whether the IOC, the U.N., or another international organisation decides to act in the name of olive oil, climate change means that North African farmers hardly have time on their side.

Austin Bodetti is a writer specialising in the Arab world. His work has appeared in The Daily Beast, USA Today, Vox, and Wired

![A Palestinian street vendor sells olive oil in front of campaign posters showing Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu [Getty Images]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2022-11/GettyImages-465764616.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=c-Z1oeXm)

![Palestinians mourned the victims of an Israeli strike on Deir al-Balah [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2024-11/GettyImages-2182362043.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=xSHZFbmc)

![The law could be enforced against teachers without prior notice [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2178740715.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=hnqrCS4x)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News