The Adventures of Champollion: Revealing the secrets of the Pharaohs in the heart of Paris

If you live in Paris, you are already concealing secrets that no one else knows: it is the city of secret keepers, dreamers, writers, and exiled individuals.

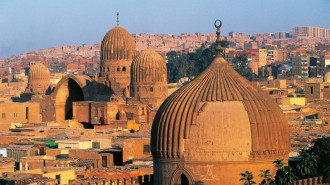

For centuries and particularly during the 19th century there was a fascination with the Pharaohs of Egypt. This period was called Egyptomania because Napoleon’s interest and his domination of Egypt provoked and enticed the spirits of Europeans and orientalists toward Egypt or its capital Cairo which used to be called Anb-Haj or Kemet in ancient Egypt.

At the same time, British scholar Thomas Young was circling the graves in the pyramid area, searching for the meaning of life, French philologist and orientalist Jean-François Champollion arrived hoping to comprehend the almost forgotten language of the future: the hieroglyphs.

"The exhibition is not only composed of 350 volumes of manuscripts, sculptors, personal belongings of Champollion, archives of his travels, research, analysis, photographs and unpublished autograph papers to highlight Champollion's scientific approach, but also his character, his intuition and his encyclopaedic work"

Under the patronage of the Minister of Culture Roselyn Bachelot-Narquin, a sponsorship agreement was made to restore the Luxor Obelisk which is located in Place de la Concorde in Paris. This sponsorship was made with Käracher in an attempt to save and protect the oldest monument in Paris.

This event coincided with the official exhibition entitled The Adventures of Champollion at The National Library of France (known as BNF) which is celebrating the 200th anniversary of the discovery of Champollion’s work.

The exhibition is not only composed of 350 volumes of manuscripts, sculptors, personal belongings of Champollion, archives of his travels, research, analysis, photographs and unpublished autograph papers to highlight Champollion's scientific approach, but also his character, his intuition and his encyclopaedic work.

There is a long history between Paris and Cairo. The Obelisk of Luxor has stood on the famous Place de la Concorde since 1836. This sculpted granite monolith was donated by Egypt as a sign of goodwill to France. It is 23 metres high and represents the right-hand stone. The left-hand stone obelisk remains in its location in Egypt.

It was Napoleon’s idea to bring a part of Egypt to Paris. On 8 October 1899 Jean Marie Joseph Courtelle, who was a French engineer, presented before Egypt’s institute in Cairo the first technical design of the monument’s location.

Later in 1830 Muhammad Ali Pasha, ruler of Ottoman Egypt officially gave the Luxor obelisks to France. In 1981 President François Mitterrand of France renounced the possession of the second obelisk and it was returned to Egypt.

Jean François Champollion never saw the hieroglyphics as an ordinary language with an alphabet; with a beginning, a middle and an end. He described it as an ideographic language based on perspectives, ideas, feelings and visuals. It is not only the sound that makes us comprehensible when we speak but also the intention behind the spoken word.

"When one stands in the middle of the first part of the exhibition, your mind wanders; what is the history of hieroglyphs? How can you develop a system of writing without logic? Maybe the Pharaoh's logic was different than ours?"

So you might wonder during the Pharaoh’s times how do conversations occur and in what form? How did the Egyptian civilisation introduce the world to love, political life, hate, war, crimes, religion, friendship, beauty, and human relationships?

Champollion was fascinated with Egypt; he described the hieroglyphics "as a complex system that can transcend in its meaning phonetically and symbolically yet contains a textual meaning. It is a language that you feel first then hear after.”

The exhibition is designed to allow you to imagine that you are walking in the same footsteps as Champollion. It is a journey that begins in 1820 and ends with his death in Paris.

The exhibition is divided, into three parts with walls coloured in shades of orange and brown, and on these walls, you see symbols of Arabic words infused with Greek, French, English and Turkish characters.

As you walk, you witness the birth of Champollion's main project which is dissecting the hieroglyphic scripts, and that during his time, another polymath named Thomas Young arrived for the same purpose; to understand Egyptians in 1822.

Champollion published his first breakthrough in the decipherment of the Rosetta hierology’s showing that the Egyptian writing system was a combination of phonetic and ideographic signs.

In 1829, he travelled to Egypt where he was able to read many hieroglyphic texts that were never studied before.

The exhibition not only highlights Champollion as the father of Egyptology but also as a human being. His passion was contagious, he worked and had immense curiosity because he felt that to be able to understand the future one must understand history. He spoke multiple languages and was fascinated with Egypt and the Arabic language.

The exhibition shows the essence of the scholar's approach and its influence until today. It builds bridges with current research on forgotten languages as well as with contemporary works kept at the BNF library.

"Champollion believed that the deciphering of the hieroglyphs was the first step toward the global discovery of the Egyptian civilization and that Egypt was and remains the centre of it all"

When you are standing in the middle of the first part of the exhibition, your mind wanders; what is the history of hieroglyphs? how can you develop a system of writing without logic? Maybe the Pharaoh's logic was different from ours, as they preferred to speak through ideas and symbols.

Relying on multilingual documents, such as the famous Rosetta Stone, Champollion translated, compared, and copied hieroglyphic texts to establish a one-of-a-kind grammar and dictionary system. His goal was to interpret the meaning of the texts and to bring back to life the civilisation that once was forgotten.

The second part of the exposition highlights the process of examining Egyptian texts by focusing on the fieldwork, so his drawings explained his way of thinking.

By the end of this journey, you arrive at a path that led Champollion to his death, he struggled a lot to be accepted in the scientific community, and he was rejected and criticised for many reasons. He managed to salvage and create beautiful discoveries during difficult times when France was in political turmoil.

He achieved another level of excellence by creating a course dedicated to Egyptology and was taught for the first time at the college of France where he was appointed as the first professor for the Department of Archaeology in 1831.

After his death, Champollion succeeded in setting up the Egyptian division in the Louvre.

The commemorations of this brilliant discovery have multiplied, paying homage to a motivated and inspiring man, as shown by the manuscripts and copies of his work.

In 1983 the poet Gerard Mace wrote a book entitled The Last of the Egyptians narrating the life and death of Champollion.

Champollion believed that the deciphering of the hieroglyphs was the first step toward the global discovery of the Egyptian civilisation and that Egypt was and remains the centre of it all.

The exhibition will be open to the public until 24 July 2022 at the National Library of France (BNF/ Francois-Mitterrand, Galerie 2). Curators of this magnificent exhibition are Vanessa Desclaux BNF Department of Manuscripts, Helene Virenque from the Department of Literature and art and Guillemette Andreu-Lanoë, an honorary director of the Department of Egyptian studies and research at the Louvre Museum.

Farah AlHashem is an award-winning Kuwaiti-Lebanese filmmaker and journalist based in Paris.

Follow her on Twitter: @AlhashemFarah

![François-Charles Cecile and Charles louis Balzac at Karnak 1798-1812. [Courtesy of BNF]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2022-04/Screenshot%202022-04-28%20120825_0.png?h=41fdedcd&itok=PJg_BXfT)

![Some of Champollion's work on decoding hieroglyphics [courtesy of BNF]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2022-04/Screenshot%202022-04-28%20120658_0.png?h=e0f37a88&itok=AItnKel5)

![Palestinians mourned the victims of an Israeli strike on Deir al-Balah [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2024-11/GettyImages-2182362043.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=xSHZFbmc)

![The law could be enforced against teachers without prior notice [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2178740715.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=hnqrCS4x)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News