All the single ladies: The Arab world's 'spinster revolution'

But women are fighting back, increasingly shunning marriage on society's terms and volunteering for celibacy without fear of that dreadful word heard at every Arab wedding: 'aabelik,' or may you be the next one to marry!

Less than two weeks before International Women's Day, this nuptial blackmail came to fresh light after tone deaf and outright sexist media in the region ran hyperbolic headlines claiming 'spinsterhood' levels among women across the Middle East and North Africa were at 'crisis' point.

The widely circulated claims seem to have originated in late February in the Arabic-version of Turkey's state run Anadolu Agency, which claimed in an article that up to 85 percent of people in Lebanon, and comparable numbers in the wider region, were 'spinsters', citing poorly sourced 'Western studies'

The articles used the term 'Anis/'Unussa, an Arabic word that means "a branch that withers and becomes useless" and roughly translates to 'spinster'. It is as equally derogatory and offensive as its English-language equivalent, yet remains in widespread use even in Arabic-language academia. And it seems its official definition is any woman (and not men) over 30 who is not yet married.

The Anadolu report called 'spinsterhood' a 'nightmare' and even urged governments to intervene. But even if we accept the dubious statistics is an increasing number of Arab women remaining single really such bad news?

|

The articles used the term 'Anis/'Unussa, an Arabic word that means 'a branch that withers and becomes useless' and roughly translates to 'spinster'. It is as equally derogatory and offensive as its English-language equivalent, yet remains in widespread use |  |

Picking off the data

The New Arab contacted a number of the leading Arab and Middle East academics studying marriage trends in the region, and they all agreed the 85 percent figure in Lebanon, and similar inflated 'spinsterhood' figures quoted for other Arab countries, were wrong.

A yet to be published paper shared with The New Arab by Dr Hoda Rashad, Director and Research Professor of the Social Research Center of the American University in Cairo and co-author of a seminal 2005 study on marriage in the Arab world published by the Population Reference Bureau, shows a number of interesting trends regarding Arab women. The paper relies on credible sources that include UN data drawn from the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division World Marriage Data 2015.

First, it is obvious we can't lump all Arab countries together in terms of demographic data. There seem to be three distinct blocs of Arab nations when it comes to marriage trends; those that still have high numbers of 'early marriage' among women with no significant delays, those that are 'transitional' intermediary countries, and those where women are marrying less at an early age and delaying their marriages.

|

In short, the data shows that in at least half of Arab countries, an increasing number of women are marrying later with a considerable number not marrying at all by the age of 40 |  |

The first group includes countries like Palestine, Syria, Yemen, Egypt, and Iraq. The second includes Morocco and Saudi Arabia. And the third, which has significant delays in marriage among women and high levels of 'spinsterhood' (the paper uses the term) include Lebanon, Bahrain, Kuwait, Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria.

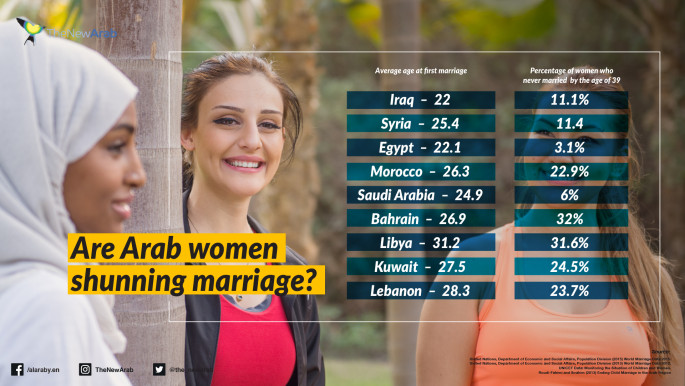

The paper defines 'spinsters' as women who were never married and are between the ages of 35 and 39. The figure of these never-married women in the Arab world seem to range from a low of 1.3 percent in Somalia to a high of 32 percent in Bahrain with Libya, Lebanon, Kuwait, Algeria being other countries with significant 'spinsterhood' (For a full data set, click here, reproduced with permission).

Another key marker that can be used to measure change in marriage patterns among women is the so-called singulate mean age at marriage (SMAM), which is the average number of years spent in single status before marriage and can for practical purposes measure the average age of first marriage.

In short, the data shows that in at least half of Arab countries, an increasing number of women – though no where near the hyperbolic amount cited in local media – are marrying later with a considerable number not marrying at all by the age of 40.

|

|

Across the Arab world, the paper says, "early marriage is no longer the standard it once was, the average age at marriage for both men and women is generally rising". The paper concludes that while these trends are part of a general global phenomenon, they are also introducing new issues into Arab societies, "issues that can confront deeply rooted cultural values and raise legal and policy challenges".

Why is Arab marriage that important?

While marriage in developed nations, where women enjoy comparably higher levels of equality and independence, is less today a condition for starting a family or a measure of a woman's achievement, the situation is the opposite in the Arab world. And anecdotal evidence suggests that this cultural marker is also valid for many women of Arab and MENA heritage living in the West, age of marriage trends among whom are likely to mirror those of their white counterparts.

According to Dr Somaya al-Saadani from the Cairo University Institute of Statistical Studies and Research, marriage in Arab societies remains "the only socially and religiously approved context for sexuality and parenting".

By no means is marriage something strictly between a man and a woman (there is no gay marriage in any Arab country). Rather, "it is an agreement... between the families of the couple... and is surrounded by great attention of their respective families and by many regulations, formal procedures," according to Saadani.

|

Marriage in Arab societies remains 'the only socially and religiously approved context for sexuality and parenting' |  |

That is because in Arab culture, marriage is a "turning point that bestows prestige, recognition, and societal approval on both partners, particularly the bride". While young men and women generally choose their own spouses, "marriage in Arab societies remains a social and economic contract between two families," according to the PRB paper by Dr Rashad et al.

Moreover, because families "are the main social security system for the elderly, sick, or disabled… (and) they provide economic refuge for children and youth, the unemployed, and other dependents," where "parents are responsible for children well into those children's adult lives, and children reciprocate by taking responsibility for the care of their aging parents... marriage for Arabs is both an individual and a family matter," according to the same source.

This means that families and society at large heavily interfere in marriage arrangements, especially when it comes to economics.

Since Arab women have been traditionally financially dependent – but increasingly less and less so – their families tend to demand male suitors offer a number of financial guarantees, which often include home ownership, an expensive dowry and agreed financial sums to be paid in the event of divorce, the Arab equivalent of a prenup.

As most Arab countries outside the oil-rich nations are struggling with low growth and high unemployment, especially among the youth, the cost of marriage has risen steadily over the past few decades, contributing to delayed marriages and increasing singlehood. However, economics do not explain alone these changing trends.

The paradigm shifts

This model where marriage stiflingly restricts interaction between the sexes, and which gives families too much power, especially over women's lives, is beginning to crack, not only because of the financial burdens of marriage but because of a conscious choice by women – as well as men, but men have always been more in control of when they choose to be married.

|

|

| International Women's Day: Special Coverage |

This conscious choice is resulting in both delays in marriage and an increase in divorce rates, according to Dr Rashad's paper shared with The New Arab. And it's not just about career or education, but also the short supply of men who have come to terms with increasingly independent, educated, successful and challenging women.

The result? Women are delaying marriage as "a calculated choice to address the incompatibility of the prevailing patriarchal marriage dynamics with increased female aspirations for autonomy and self-realisation," according to the paper.

"More women are choosing to be single and this is a very good sign, as a lot of women are putting their career as a priority," M.A., a Lebanese single woman in her 30s, told The New Arab.

"As a woman, the term spinster offends me… because it is a very negative and sexist word that limits women to their traditional role of getting married and having a family. This term totally neglects and ignores the free will of women who decide not to be married," she adds.

"Society puts a lot of emotional and social pressure on women who decide not to get married. They always try to convince us that, if we didn't get married and have children, we will end up lonely and sad. Over the past few years, I have worked hard to build a successful career... but some family members still think that this is something temporary until I find my prince charming."

|

More women are choosing to be single and this is a very good sign, as a lot of women are putting their career as a priority |  |

'Let her stay spinster'

Arab parents, men and patriarchal systems have not caught up with these choices that an increasing number of educated career-minded women are making.

Although countries like Morocco and Tunisia have made some progress, most Arab legal systems still discriminate against women in matters of marriage, divorce, nationality laws, and even taxation. In Lebanon, a woman cannot claim income tax deductions for her children unless she is the family's sole breadwinner or if the children's father is dead or has a disability.

Why? Because the system sees women as only wives or mothers, rather than independent agents.

It is no surprise then that single women – by choice or otherwise – are bullied and called 'spinsters' by everyone from the media to obnoxious men on YouTube, one of whom in the wake of the viral Anadolu article made a video urging women to lower their impossible standards and stop being so materialistic.

That sense of male entitlement reminiscent of the incel movement is so strong among Arab men that they are literally launching wars on single women, at least online. Last week, Egyptian men even created a hashtag (Let Her Stay Spinster) bullying women who are choosing careers over settling.

"We are threatened that we may end up 'spinsters' as soon as we have a minimum of expectations or standards concerning who we want to marry, or as soon as we are outside of the box (physically by being not feminine enough for example, or mentally)," H., a French single woman of Arab heritage in her 20s, told The New Arab.

"I see the term 'spinster' like a punishment for the women who refused to settle... We end up feeling alone not because we are single, but because our family is not supportive, and very judgmental."

|

In Lebanon, a woman cannot claim income tax deductions for her children unless she is the family's sole breadwinner or if the children's father is dead or has a disability |  |

Brave new (Arab) world

With more and more Arab women accessing education and the labour market, where many are outperforming their male counterparts, pressure will grow on Arab patriarchal systems in the region and the diaspora to adapt and let go of their obsession with 'spinsterhood'.

Rather than a 'spinster crisis', what seems to be happening is a 'spinster revolution', if we want to appropriate the offensive term.

Not only are Arab women taking charge of their destinies by delaying marriage or remaining single, they are fighting the system back.

As Rothna Begum wrote in The New Arab exactly one year ago, this is an exciting time for women in the Middle East, where important legal and policy changes in the region are being driven by women human rights defenders.

These women are not waiting for anyone to grant them their rights, but are bracing harassment, intimidation, and even imprisonment to force their oppressors to reverse systematic discrimination across the region, especially in laws relating to marriage, divorce, child custody and inheritance.

If there is a real societal problem arising from the collapse of the old marriage model, then this is part of the solution. If women feel laws and policies are fairer then they will be less intimidated by the currently oppressive marriage bond.

But perhaps the Arab world should reconsider its obsession with marriage as the be all and end all of a woman's life.

"To be married means I would no longer be able to do the work I love and enjoy, to be married means I would probably have to have children, which I can't picture myself doing it all," M., a Palestinian woman in her 30s, told The New Arab.

"Marriage is good for those who really want it, but it's not for me, so let them call me a spinster."

Karim Traboulsi is an editor at The New Arab.

Follow him on Twitter: @kareemios

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News