Anamorphosis: Praneet Soi responds to the conflicts in Palestine and Kashmir through art

The conflicts in both Palestine and Kashmir are regularly covered by the international media, often projecting news and visuals of violent clashes between Israelis and Palestinians, and Kashmiris with Indian forces.

However, what is lost in these representations? What are the daily lives like for the people living in such conflicts? And what cultures and traditions are overlooked by the international world?

These are some of the questions asked by Praneet Soi in his new exhibition, Anamorphosis: Notes from Palestine, Winter in the Kashmir Valley now open at The Mosaic Rooms in London.

The exhibition tracks the artist’s time in both Palestine and Kashmir, combining digital footage with diary extracts, drawing and painting, to offer the audience a glimpse of his experience in each location.

The first floor is centred around Soi’s time in Palestine, where he considers the landscape as a place of contention, livelihood, and control of movement.

The second floor then turns to Soi’s ongoing project in the Kashmir Valley where he worked with local artisans to explore Sufi culture in the region.

Soi explained during a press tour that his decision to include Kashmir in the exhibition occurred a short while ago when India revoked Article 370 of its constitution, ending Kashmir’s autonomous rule.

"A month and a half ago, the whole relationship between India and Kashmir turned upside down and India pulled Kashmir back into its grip," the artist said.

"When this happened, it became imperative to put the two together."

Yalla Yasmeen! is the first work seen by visitors as they enter the gallery. A short film made up of seven chapters, it documents Soi’s brief time in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Israel in 2019, with each chapter uncovering the different moments, spontaneous meetings, and chance encounters, that occurred during his journey.

From the historic lands of Sebastia, home to ancient olive trees up to 2,000-years-old, to the farmland of Salfeet that borders the contentious Israeli settlements, and the railway tracks of Bettir that once formed the border between Israel and Jordan, each snippet reveals the highly complex history of the land and the challenging circumstances that Palestinians are forced to deal with in daily life.

|

|

| Read also: On Arid Lands in Ethiopia: Aïda Muluneh's exhibition responds to the global water crisis |

One encounter demonstrates the complexity of the conflict for Palestinians who rely on the Israeli economy for their livelihood.

The scene takes place at a hardware shop just outside the city of Salfeet in the West Bank, close to the Israeli settlements Barkan and Ariel.

Set up by a Palestinian named Murad, the shop’s main customers are Israeli settlers, given the rapid construction occurring in the settlement.

Murad’s cousin, Hafez, describes the complexity of the situation: "You have to be in a mindset where you know this is not normal but if you don’t accept it you will not be able to make a living."

Soi explained that it was these moments of interaction that interested him most during his visit: "One thing that struck me is that there is a dialogue going on between the Israelis and the Palestinians, between the farmers or small-store owners and the settlers. There is an economy that exists between them, however tenuous, and it is one-sided… but I found that interesting and I try and address those issues."

Other parts of the film capture moments of relief for young Palestinians. On the final day of his travels, Soi stopped by the Palestinian city of Akka, located within the Israeli state.

Bordering the Mediterranean Sea, the scene shows young Palestinians jumping off a high wall into the sea. A young woman called Yasmeen, of who the work is titled after, is drawn into the fun but stands on the edge, too afraid to jump, as everyone around joins in beckoning her into the water.

"These moments for me really made my time in Palestine come alive," Soi explained. So moved by what he saw, the artist too plucked up the courage to jump.

In the next room, a large wooden installation holds sketches, diary exerts, and paintings that Soi created during and after his visit to Palestine. The structure itself is somewhat impenetrable, full of twists and turns that echo the boundaries and restriction of people’s movement within the conflict zone.

|

|

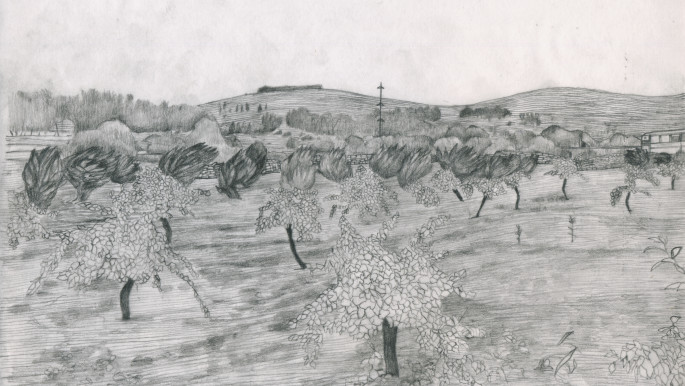

| Vineyard, Beit Ummar, Graphite on tracing paper, 2019. Courtesy of the artist |

|

|

| Falling Figure, Set of three tiles, 2019. Courtesy of the artist, Photographed by Ilya Rabinovich |

"I was always disorientated when I was in Palestine," Soi explained. "I think the structure tried to talk about it through peripheral views, barricades, the accessibility and inaccessibility of certain places. For me, the most amazing thing was to try and understand that we are looking down into a landscape across a city and it is absolutely impossible to move from one space into another."

This distortion is echoed in the work Bettir, in which the historic village of Bettir has been transformed into an anamorphic landscape, curled and stretched to appear almost surreal. This technique of altering a landscape was then taken as the title for the show.

"Anamorphosis is an image that has been distorted," Soi described to The New Arab. "It was used in medieval times to hide images. I think I was using it as a metaphor because anamorphosis stretches and creates distortions and abstraction, so you are never clear. I think that is what is happening in Palestine, you are never clear what your limits are – can you go here? Can you go there? Is this one landscape or three?"

Hanging on either side of the installation are two portraits of farmers featured in the film. Their wrinkled faces and haggard expressions represent the struggle that many Palestinian famers face. Placing the portraits on either side, Soi pays homage to them all.

"The farmers are the real heroes of the land," he said. "They are the people who really face the problems because the Palestinian Authority has no help for them. They are subject to the Israeli Defence Forces and the settlers, and whatever problems come their way have to be taken in strife by them."

The final section is dedicated to Soi’s engagement with artisans from the city of Srinagar in the Kashmir Valley. The room is painted black so that sharp bursts of light dramatically uncover the beautiful tiles that Soi crafted with the aid of Fayaz Jan, a master craftsman from the city. They draw on Sufi culture in Kashmir.

"What I am doing while I am there is to constantly go deeper into the Sufi culture of Kashmir which is largely forgotten," Soi explained.

In Kingfisher, three tiles join together to create a brightly pattered geometric form that echoes the Islamic motifs found in Sufi architecture. Made from papier-mâché with acrylic painted on top, the work references the introduction of papier-mâché to Kashmir which entered from Iran, much like Sufism.

Historically, Sufi saints from Kashmir would travel across Central Asia and Iran, spreading Islam and advocating the importance of craftsmanship.

Written in chalk on the walls are excerpts from Soi’s notes during his time in Kashmir, as well as extracts from the United Nations’ resolution number forty-seven from 1948, calling for a plebiscite in the region allowing Kashmiri residents to decide on their future with either India or Pakistan, something unfeasible today.

The exhibition leaves the viewer with a different, more human understanding of the conflicts in Palestine and Kashmir; the ways in which conflict affects the daily lives of the people and the traditions and cultures that are threatened because of it.

Anamorphosis will be on display at The Mosaic Rooms, London until December 7

Georgia Beeston is a freelance journalist based in London with a focus on arts and culture from the Middle East.

Follow her on Instagram: @theartcompass