Saudi gives Salafism a PR makeover after 'extremist hijacking'

Events 300 years ago in a small, nondescript village outside Riyadh paved the way for seismic shifts in the Arabian Peninsula, the repercussions of which are still being felt today.

Addiriyah was home to a controversial, but then little-known, religious scholar named Mohammed ibn Abdel Wahhab, who formed an alliance with the local al-Saud family - which still rules Saudi Arabia today.

The location of this marriage of convenience is today set for a major overhaul, transforming the town's mudbrick district into a historical quarter and making Addriyah a cultural capital of Saudi Arabia.

The UNESCO site is where Abdel Wahhab first preached the virtues of a Lutheran-like austere way of life. By the end of this year Addriyah will include a foundation named after the cleric.

Saudi hopes the centre will be an "international hub for researchers in Islamic studies".

Three centuries' tradition

Abdel Wahhab espoused a completely inflexible variant of Islam that forbid iconography, music or lavish individualism.

It has become a state-sanctioned creed in Saudi Arabia, and now claims millions more adherents across the world, extending Riyadh's reach abroad.

"The new centre is an attempt by the Saudi Arabian authorities to reaffirm what they see as the legitimate interpretation of Abdul Wahhab's legacy, rather than to reclaim it, as that suggests they had already lost it," said Jane Kinninmont, deputy head of the Middle East and North Africa programme at Chatham House.

Salafism - or Wahhabism as it also became known - is once again being co-opted by the Saudi regime after suffering years of bad press after becoming associated with jihadi terrorism and beheadings.

"That's not just a pedantic point: it reflects the fact that this is a constant, dynamic effort," said Kinninmont.

"Saudi Arabia has been dealing with challenges from political Islamist groups since the 1970s, and has faced violent jihadi attacks within the country since 2003, so while the threat has flared up again recently, it is not something new."

The Middle East researcher believes that a "battle of ideas" has taken place in Saudi Arabia since the emergence of al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group as threats to the current world order.

After years of al-Qaeda attacks in Iraq and other places, sympathies for the group among Saudis shifted when the group targeted Riyadh's security forces.

Saudi Arabia has seen a more recent resurgence in nationalism, when suicide bombers targeted Shia mosques in Saudi Arabia and lost many supporters in the kingdom.

| Within Saudi Arabia's official and media discourse, al-Qaeda and IS are typically described as deviants. |

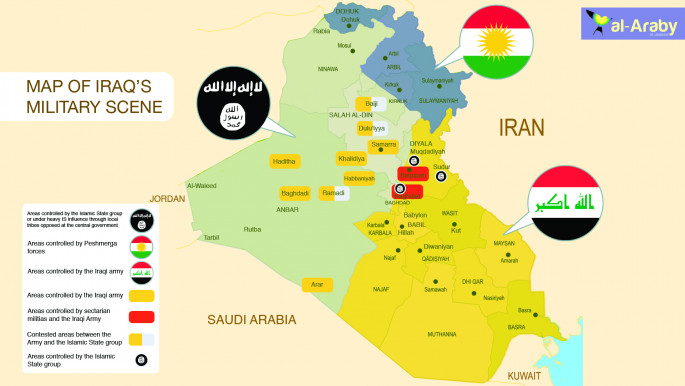

The Islamic State group is one of the greatest threats to the ruling Saudi royal family in many years.

Its self-proclaimed state in parts of Syria and Iraq - ruled by self-appointed "Caliph" Abu Bakr Baghdadi - gives its militants a base to target the kingdom, and the extremist group boasts thousands of Saudi members.

Now that Pandora's box has been opened on Saudi Arabia's border in Yemen, there is a very real possibility that the group could expand its presence in the country.

This brutal and extremist mutation of Wahhab's doctrine has seen slavery and public torture becoming commonplace in IS territories.

Abdel Wahhab books are also said to be widely distributed in Raqqa and Mosul.

Khajarites

In turn, Saudi Arabia - which has codified in law Wahhab's interpretations of Islam - has dismissed IS as being "Khajarites".

The Khajarites were a rebellious Muslim faction in early Islam that rejected all authority but their own.

Members - usually young men - promised death to rival rulers, particularly secular kings and sheikhs.

"There has been mounting criticism of 'Wahhabism' by analysts who think that this interpretation of Islam has helped inspire IS," said Kinninmont.

Most Saudis who claim to follow the mainstream, state-sanctioned interpretation of Abdel Wahhab's teachings believe that IS have deviated from this path

"The mainstream, state-sanctioned religious tradition in Saudi Arabia forbids political violence by non-state actors and emphasise the importance of order and obedience," the researcher added.

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

"Within Saudi Arabia's official and media discourse, al-Qaeda and IS are typically described as deviants to emphasise their theological heterodoxy."

Saudi Arabia's claim that Abdel Wahhab was a reformer, not a revolutionary, allows Riyadh to criticise IS for its claims that the Saudi royal family is illegitimate, despite both groups converging on many similar points of view.

Riyadh practices a version of Sharia not dissimilar to IS' own, which includes public beheading, flogging and amputations.

Dozens of historic sites associated with the Prophet Mohammed and his family in Mecca and Medina have been bulldozed to make way for five-star hotels and expansions of the Grand Mosque.

Saudi clerics claim that these measures are to prevent piles of rocks from being worshipped, "in the way Christians do".

Reformation

These measures largely follow IS' script. The group has dynamited ancient temples in Palmyra and Nineveh dedicated to gods forgotten long ago.

At the same time, Saudi Arabia hopes it can transform Abdel Wahhab's mudbrick home village into a secular piligrimage site for Saudis as well as a centre for Islamic learning.

These appear to be attempts to fit Abdel Wahhab into a more contemporary framework.

By emphasising the cultural impact of the scholar and the "reformist" legacy he left, he can be shaped into a pioneering religious figure and founding father of Saudi Arabia - two elements which are hard for the al-Saud family to separate.

Gulf countries have attempted to forge national identities based on more secular and militaristic impulses - and Saudi Arabia is no exception.

This is to ensure the loyalty of a growing, young population and to patch up religious, tribal and geographical differences.

At the same time, Saudi Arabia has introduced a number of conservative measures it hopes will appease potential IS recruits, including a 1,000 riyal fine ($263) for women who break Saudi Arabia's strict "Islamic" dress code in their workplaces.

These measures are undoubtedly an attempt to accomodate the many sympathisers for the militant group inside Saudi Arabia, said al-Araby al-Jadeed's Saudi Arabia correspondent.

Riyadh has largely won the support of the country's Salafi clerics by putting them on the state payroll and regulating mosques and sermons.

Kinninmont said that there was still a debate about how important the clerics are in modern-day Saudi Arabia.

Most Saudi subjects are more concerned with their own living standards than the religious legitimacy of the government.

A case in point is the relative ease with which King Abdullah managed to gradually reduce the influence the clerics held over the country's education system.

However, there are still very real threats of unrest in the kingdom.

Low oil prices and tensions with Shia-majority Iran, along with an expensive war against Zaydi-Shia Houthi rebels in Yemen all threaten the relative stability King Salman's predecessor achieved.

"[King Abdullah] had even begun to [reform] the justice system, relative to what had been the case before, without facing a significant [religious] backlash," said Kinninmont.

"But this may be the view of a limited elite in a country where many in the country remain deeply religious."

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News