As Lebanon grapples with economic collapse and a coronavirus outbreak, refugees appeal for international help

With economic circumstances becoming increasingly difficult in Lebanon now also hit by a coronavirus outbreak, and with little hope of resettlement abroad, an increasing number of Syrian refugees have loaded their belongings onto buses and returned to their country and to an uncertain fate.

Meanwhile, those who see no option of returning to their war-torn country have been mounting protests in front of the offices of the UN refugee agency, calling for more attention to their cases.

According to UN statistics, a total of about 38,500 registered refugees have returned from Lebanon to Syria since 2016, including about 21,000 who have returned in organised 'voluntary return' trips that Lebanon’s General Security agency has been coordinating with the Syrian regime since April 2018.

"People are being pressured to return in the 'voluntary returns'," Sawsan Kalash, one of a group of Syrians who began staging a daily sit-in in front of UNHCR's Tripoli office since December, told The New Arab.

"But no one returns voluntarily. People are returning because of the injustice and oppression and poverty and sickness."

'Perfect storm'

The numbers of Syrians returning in the General Security-organised trips appear to have increased since Lebanon has been hit by a 'perfect storm' of financial crisis and mass protests that hit in the last quarter of 2019, while the current outbreak of the novel coronavirus Covid-19 in the small country risks hitting them disproportionately in light of their tough living conditions.

|

In late August, 787 Syrians returned in that month’s 'voluntary return' trip. During the most recent of those trips, on Feb. 13, buses carried 1,093 Syrians back across the border from Lebanon.

On the same day, several dozen other Syrians were protesting in front of UNHCR's office in Tripoli, as they have been nearly every day since December.

"If the Syrian is forbidden to work, and aid is not arriving from the UN and he’s not able to go back to his country, what’s the solution?” Kalash asked.

"We decided to do a sit-in in front of the UN building to get our voices heard and... put pressure on the UN to consider our situation."

No resettlement hope

UN officials said their hands are tied by the lack of available resettlement places and funding.

|

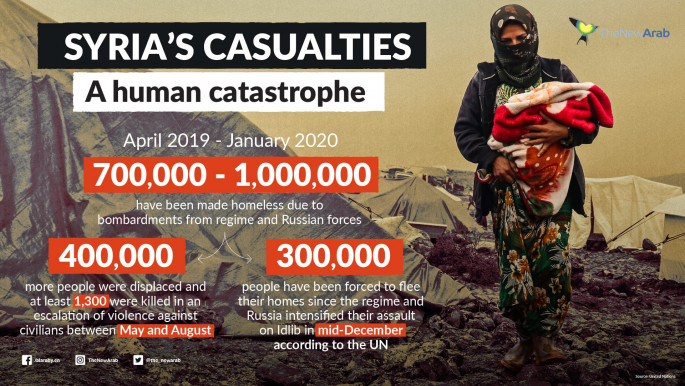

| [Click on the graphic for a larger version] |

In a statement issued in response to the refugee protests, Mireille Girard, UNHCR's Representative in Lebanon said: “While we are working hard to further expand assistance, we remain severely constrained by funding limitations. This is forcing us and other humanitarian agencies to prioritise the most vulnerable refugees."

"Many refugees hope to be resettled to a third country, as they do not see how to cope with the current situation. While we understand their hope for a solution, it is important to stress that the number of resettlement places remains extremely limited worldwide,", she added.

Less than one percent of the world’s refugees find resettlement places each year.

UN representatives confirmed that economic pressures seemed to be contributing to the increasing number of returns, with many refugees citing increased food prices and inability to afford essential items as reasons for returning.

|

It is not up to UNHCR or anyone else to make the decision to return on behalf of refugees --UNHCR spokesperson |

|

Penury in Lebanon, mortal danger at home

Most of the Syrians who spoke to The New Arab said they were months behind on their rent and facing eviction – or had already been evicted. Some had family members with medical conditions not covered by UNHCR aid, including cancer. Several of them said they had pulled children out of school because of the increasing economic pressure.

Khadija al Omar said in nine years as refugees in Lebanon, her family had only received one month of cash assistance from UNHCR, to help with the costs of heating.

“My son goes and sells tissues on the street,” she said. “Is this what I wished for my son, to go and sell tissues when he’s eight years old?... If I could return to my country I would have – I wouldn’t have stayed until now.”

Like Omar, Ramez Mohammed Halabi said his family is not receiving aid and his four children – aged six to 12 – had to drop out of school this year because he could not afford the cost of transportation and other expenses.

The last time he went to the UNHCR office to appeal for assistance, Halabi said, “The employee told me, ‘Go with the voluntary return, register and go.’ I’m from Idlib – Idlib is under fire.”

|

|

UNHCR spokeswoman Lisa Abou Khaled said there might have been a “misunderstanding” in the case.

“It is not up to UNHCR or anyone else to make the decision to return on behalf of refugees,” she said. “Our staff are very clear on that. Return is fundamentally a human decision; each family has a different situation. It is not up to us to tell them or decide on their behalf.”

The fate of those who have returned, in some cases, is unclear. In theory, General Security runs the list of potential returnees by Syrian authorities to ensure that none of them are wanted for arrest should they return and turns away those whose names are on “wanted” lists.

But there has been no comprehensive tracking of what has happened to the returnees, with some UN officials complaining about lack of access to returnees in Syria.

“Today they’re registering people for the ‘voluntary return’ to Syria,” said Hiba Shinno, a Syrian from Hama living in Tripoli. Nine months ago, she said, “My uncle’s household registered and went back on one of the trips and then they went missing. We can’t find out anything about them….My husband’s brother, the same thing happened. He also got to the Syrian border and went missing.”

So, Shinno said, she and her husband are not considering going back, although their situation in Lebanon is difficult. They have two special-needs children who are not going to school – the public schools, which generally teach Syrian children in “second shift” afternoon classes, would not accept them, and the family can’t afford to put them in private school.

“If (schools for them) aren’t available here, give us documents to allow us to travel,” she said. “We can’t go to Syria. If I went to Syria, I don’t know if the regime would take me or not -- me and my husband and children.”

Abby Sewell is a freelance journalist based in Beirut

Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News