What's really behind Saudi Arabia's inclusion of Chinese as a third language?

Saudi Arabia has officially implemented Standard Chinese as a third language in the country's schools. The first phase is currently underway and includes lessons taught in a total of eight secondary schools for boys only in three Saudi cities: Riyadh, Jeddah and Dammam.

Part of the comprehensive Saudi Vision 2030 programme, the government plans to eventually also teach female students Chinese as an optional third language and will extend lessons beyond secondary school to university education. After Arabic, English serves as the second language in Saudi Arabia.

While economists worldwide are preoccupied with the idea of learning Chinese as a means to navigate global markets, this addition to Saudi curriculums reveals a carefully planned strategic partnership that points beyond linguistic improvement and cross-culturalism.

The decision to instil Chinese in Saudi schools was initially made during Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's Beijing visit to China in February 2019, as one of the many agreements signed between the prince and Chinese president Xi Jinping.

The meetings led to a total of a total of 35 economic cooperation agreements and an arrangement for Saudi Arabia to hold a cut in Chinese tourism via joint investments.

Read also: 'China is a good friend to Saudi Arabia': MbS bags $10 billion Beijing oil deal

|

|

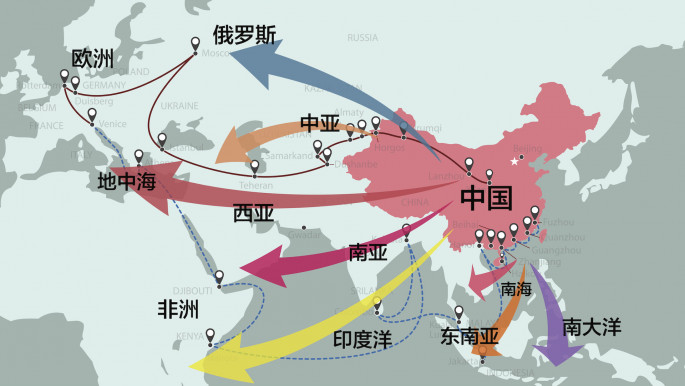

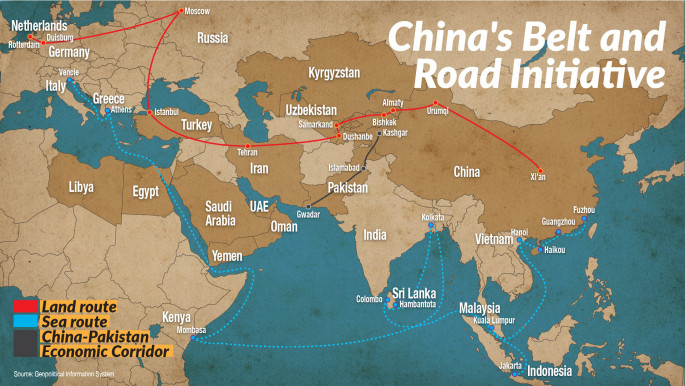

| Read also: Belt and Road Initiative: As America's power fades, China lures Arabs into its sphere |

US economic sanctions against China also led to a decrease in exports from Iran, Saudi Arabia's competitor in the region.

Within a one-year period, a 77 percent jump of 1.98 million barrels per day (bpd) were sent to China, where 400,000-barrel capacity refineries were implemented in 2019.

The rapid spike stems from the $10 billion mega-project between Saudi Aramco (the kingdom's official oil company) and the Chinese independent oil refinery complex, Zhejiang Petrochemical, of which Aramco now holds a 9-percent stake.

|

The decision to instil Chinese in Saudi schools was initially made during Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's Beijing visit to China in February 2019 |  |

That deal derives from an even greater $28 billion trade agreement between Riyadh and Beijing that would benefit both China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Saudi Vision 2030 programme.

Vision 2030 involves shifting the country's economic prospects beyond its oil dependency, finding additional sources of revenue, and expanding its private sector.

The plan also includes an implementation of social – not political – reforms, which mention everything from increasing public participation in athletic activities to a vague "Strategic Partnership Vision Realization Program;" presumably, China is the leading partner in mind here.

|

|

As with the integration of Chinese into Saudi curriculums, news of these loosely defined social programmes come from regurgitated press releases circulated by media outlets regulated and subsidised by the Chinese and Saudi governments.

These memos echo the two countries' sentiments, stating the deals will "foster stronger relationships" and "cultural cooperation," along with solidifying "bilateral" tourism, commerce, and technological goals, which all sounds lovely if it weren't for the subtext of the agreement.

In reality, they benefit countries already saturated in wealth, but for whom and at what cost? Can the measure truly promote "diversification" within the kingdom's economic prospects, when actual diversity within the lower echelons of the Saudi labour force is met with cruelty?

A staggering majority of the kingdom's labour workers are comprised of disenfranchised non-Saudis, in particular from significantly poorer countries in Africa and Asia.

|

As the world condemns China for the detainment of its own ethnic Uighur Muslim population, Saudi Arabia, as well as several other leaders of majority-Muslim nations, continue their support of China |  |

Migrants are often subjected to horrendous living and working conditions, with employers confiscating their passports and taking virtual ownership of their employee's lives. Beyond the physical and verbal abuse suffered at the hands of their employers, migrant workers have no set minimum wage, nor do they have any labour agencies to protect them.

As the Center for Democracy and Human Rights in Saudi Arabia documents, "Embassies of foreign workers often side with the Saudis for fear of losing Saudi loans, favourable trade deals, and access to cheap oil."

Part of the new language programme will fund bilateral job opportunities that will certainly not benefit labour workers but estimates an expansion of up to 50,000 jobs for Saudi citizens.

Read also: Can the tourism sector in Saudi Arabia prove to be sustainable?

In truth, the connection between Saudi Arabia and China does not rest in the two countries' mammoth global economic prestige or decades-long relationship, but the numerous human rights abuses held against them.

|

|

| Read also: China's Uighurs: A genocide in the making |

To note one of many examples, both countries hold troubling records of silencing their dissidents and members of the media. When journalist Jamal Khashoggi was killed at the hands of Saudi diplomats, China – no stranger to stifling its own media body – enacted the billion-dollar trade deal only a few months after Khashoggi's murder.

And as the world condemns China for the detainment of its own ethnic Uighur Muslim population, Saudi Arabia, as well as several other leaders of majority-Muslim nations, continue their support of China.

While some leaders chose complicity in silence, the Saudi Crown Prince verbally defended China's concentration camps, stating that the country "...has the right to take anti-terrorism and de-extremism measures to safeguard national security."

"Saudi Arabia respects and supports it and is willing to strengthen cooperation with China," he followed.

Saudi Arabia is not the only country in the Middle East rushing to generate economic agreements with China while compromising their stance on the country's treatment of Uighurs.

|

The Middle East and China both prioritise economic growth over political reform; the way they see it, their governing entities prefer investing in the trade of goods over the instability and threat of a political reform movement |  |

The Middle East and China both prioritise economic growth over political reform; the way they see it, their governing entities prefer investing in the trade of goods over the instability and threat of a political reform movement.

Middle Eastern leaders fear another Arab Spring – especially in monarchy-led countries – and thus focus on vague, buzzword-laden projects like Vision 2030 (or Kuwait's Vision 2035 or UAE Vision 2021).

For China and Middle Eastern countries like Saudi Arabia, it's easier to maintain a free-flowing economic partnership without either country claiming a moral high ground over the other – as, in their eyes, often is the case with the West.

Hind Berji is a freelance writer with experience in arts reviews and sociopolitical criticism.

Follow her on Twitter: @HindBerji

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News