Little hope for change among Sudanese refugees fleeing violence in Darfur

"In the beginning there were planes bombing the area. In November 2003, the Janjaweed came. There were rapes, beatings. They killed my father and stole our cattle," he says, referring to the Arab militias recruited by Omar al-Bashir's government to crush an ethnic minority rebellion in Darfur.

Rebels accused Bashir's government of marginalising the region. The insurgency was suppressed with brutal force.

According to UN estimates, the Sudanese government's brutal counter-insurgency campaign in Darfur has left at least 300,000 people dead and 2.7 million displaced since 2003.

Human rights investigations have revealed how Darfuri civilians have been systematically targeted for murder and rape.

"I fled to Chad with my mother and my sisters. I spent 10 years living in a refugee camp called Iridimi," says Ahmed. In 2014, he left the refugee camp and sought asylum in Jordan.

When the uprising against Omar al-Bashir's government started in December last year, Ahmed had been living in Amman as a refugee for nearly five years.

Like most of the around 6,000 Sudanese refugees in Jordan, he followed the protests closely online.

Ahmed was appalled when he saw videos of the violence unleashed on protesters in the street s of Khartoum on June 3. But he was not exactly surprised.

The images and videos of men dressed in fatigues beating and intimidating unarmed protesters looked painfully familiar. Darfur had come to Khartoum.

On June 3, security forces broke up protests in Khartoum in an operation that, according to the Central Committee of Medical Doctors, left 128 people dead. A report prepared by state prosecutors only confirmed 87 deaths.

Bodies were thrown into the Nile and hospitals reported over 70 rapes. Protesters blamed the violence on the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), formed from the former Janjaweed militias accused of crimes against humanity in Darfur.

|

We have been experiencing this kind of violence for over 16 years |  |

"We have been experiencing this kind of violence for over 16 years," says Adam, a Darfuri refugee who fled Sudan in 2013 and also sought asylum in Jordan.

|

|

| Read also: 'Fighting for our stolen rights': Sudanese women call for social justice revolution |

The Janjaweed militias were sent to attack Darfuri villages as part of a brutal campaign that led Bashir to be indicted for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide by the International Criminal Court.

Like Adam and Ahmed, many Darfuri refugees saw the crackdown on protesters in Khartoum as a continuation of atrocities committed in Darfur.

Already too familiar with the brutality of the Janjaweed, refugees from Darfur argue that the violence used recently against protesters has been perpetrated by the same forces. Formed from the former Janjaweed militia, the RSF have been accused of widespread human rights abuses.

A week after the attack on protesters, Amnesty International said that Sudanese government forces, including the RSF and allied militias continue to commit war crimes and human rights violations in Darfur.

"In the past year these have included the complete or partial destruction of at least 45 villages, unlawful killings, and sexual violence," Amnesty International's report read.

But human rights activists say that unlike the violence on June 3 in Khartoum, which was filmed by protesters and widely shared online, ongoing violence in Darfur remains largely undocumented and brutality continues to be used against civilians with impunity.

"In our region nobody has the money to buy a smartphone. We don't have the same kind of access to the internet to post photos and videos," says Adam. "This type of things has been going on for a very long time. But no one is interested in reporting on it."

Adam fled his village in 2004 and spent four years in a refugee camp called Kalma in southern Darfur. With around 90,000 residents, Kalma was one of the largest camps for Darfur's displaced people.

Adam says his camp was attacked by paramilitary forces associated with the Janjaweed in August 2008.

"They came and surrounded the camp, 35 people were killed and over one hundred people were wounded," says Adam, adding that the incident was barely reported. He says that Radio Dabanga, an Amsterdam-based radio, is one of the few news outlets regularly reporting on human rights abuses in Darfur.

|

|

|

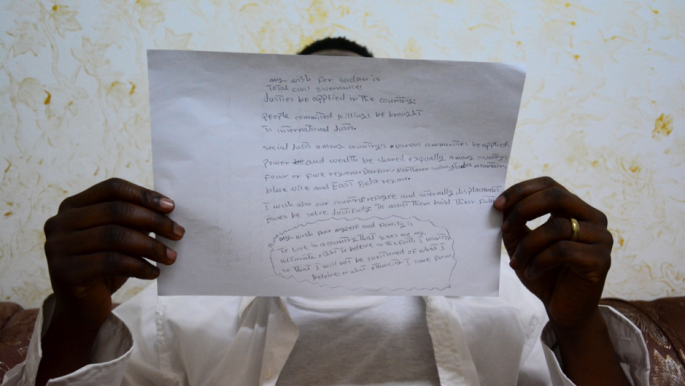

"My wish for Sudan is total civil governance," writes Adam on a white paper he holds in front of his face. He still fears for his safety so he chose not be identified [Marta Vidal] |

Adam fled conflict at home but he did not find peace in Amman. Sudanese refugees in Jordan often complain of discrimination and feel neglected by humanitarian organisations and local authorities. Despite being unable to work, they receive limited humanitarian assistance.

Jordan hosts the world's second highest number of refugees per capita, and overburdened NGOs tend to focus on Syrian refugees who are the majority. So many Sudanese refugees in the country are left to fend for themselves.

|

Sudanese refugees in Jordan often complain of discrimination and feel neglected by humanitarian organisations and local authorities |  |

Sudanese refugees' hopes and fears

Triggered by economic collapse, protests started in the northeastern city of Atbara in December but quickly spread across Sudan. Protesters demanded an end to Bashir's three-decade authoritarian rule.

On April 6, protesters occupied the square in front of the military headquarters. Five days later the military arrested Bashir and announced the formation of a Transitional Military Council. But protests continued to call for the transfer of power to civilian rule.

|

|

| Read also: Sudan: This time it's different |

"Bashir's regime has survived under the new political landscapes in Sudan but without the big boss at the head of it. The system that he created turned against him," says Suliman Baldo, a senior policy adviser at US-based NGO the Enough Project.

"These generals want to retain their power and preserve the system that Bashir created."

The Transitional Military Council (TMC) is led by lieutenant general Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, but its most prominent member is general Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, widely known as Hemeti, the leader of the RSF.

Hemeti's forces have been deployed to crush insurgencies across Sudan, and its mercenaries are also fighting in Yemen as part of the Saudi-led coalition.

"There is no trust," says Abdel, who fled Darfur in 2010 and became a refugee in Jordan. "Hemeti is responsible for the killing of Darfuris for many years and now he is in the centre, dominating the TMC."

For Sudanese refugees in Jordan, Bashir might be gone but the old regime remains in power. They say the military that removed him after months of protests holds responsibility for the violence they witnessed in Darfur.

After Bashir was overthrown, persistent protests for civilian-rule forced the military to enter negotiations with pro-democracy movements represented by the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC). Talks between the TMC and the FCC were mediated by Ethiopia and the African Union and went on for months.

A deal signed on July 17 aimed to set up a joint civilian-military ruling body. On August 3, military rulers and protest leaders announced they had reached a final power-sharing deal. They agreed on a constitutional declaration which will pave the way for a promised transition to civilian rule.

The agreement will establish a joint civilian-military ruling body which will oversee the formation of a transitional government.

A formal signing ceremony will take place on August 17. In the following days, generals and protest leaders are expected to announce the composition of the new transitional ruling council.

But refugees are expressing their reservations about the agreement.

"They have signed an agreement with this military junta that has killed recently a big number of peaceful protesters. How do we trust the same bloody military generals?" asks Adam.

According to the agreement, the paramilitary RSF will be overseen by the Sudanese army. The transitional council will be headed by a general during the first 21 months and then followed by a civilian for the remaining 18 months. During the negotiations one of the most contentious issues was the military generals' demands for immunity from prosecution.

The deal established that immunity could be lifted with permission from the legislative council. But Darfuri refugees in Jordan are not convinced.

"If there is any justice, the first thing would be for the military to be brought to court, but that is not going to happen," adds Adam.

A Human Rights Watch dispatch said that the RSF, led by Hemeti and accused of serious human rights violations, is now "more powerful than ever before, with little reason to fear being held to account for violations and crimes against civilians."

Refugees will only feel safe to return to Sudan when all semblances of the previous regime are removed. But with generals holding on to power, they think significant change is unlikely in the near future.

Despite his distrust that the military will ever be willing relinquish power and the hardship he has endured living as a refugee for the past 16 years, Ahmed holds on to glimmers of hope and forgiveness.

"I could forgive the people who killed my father, burned my village and stole our cattle if there was a chance for reconciliation and real democracy," he says.

(*) Last names have been withheld to protect identities

Marta Vidal is a freelance journalist who writes about social justice and human rights

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News