Norway and Germany have banned weapons sales to countries fighting in Yemen. Will others follow?

In the past month, three European governments have suspended the export of munitions and arms to Gulf countries involved in the war in Yemen.

In January, Norway suspended exports to the United Arab Emirates as a "precautionary line", based on its assessment of the situation in Yemen, where a Saudi-led coalition including the UAE has been fighting Shia Houthi rebels for nearly three years now.

Days later, Germany followed, also stopping arms exports to countries involved in the Yemen war, where more than 10,000 people have been killed and another three million displaced, while a cholera epidemic is sweeping over the Arab world's poorest country.

The paper written by Chancellor Angela Merkel's CDU/CSU grouping and the Social Democrats states "the federal government, with immediate effect, will no longer export arms to countries as long as they are involved in the Yemeni war".

Besides Norway and Germany, the Walloon regional authority in Belgium announced it would no longer authorise any licenses to the Ministry of Defence of Saudi Arabia for military equipment that could be used in the Yemen conflict.

The autonomous region has also suspended export licenses to the UAE. Walloon is one of three regional authorities in Belgium that can make independent arms transfer decisions. So is the tide turning - and will other European states follow these examples?

Anti-war coalition is growing

Even before the recent decisions of Norway and Germany, EU member states have been pulling the plug on exporting weapons to Saudi Arabia - either completely or at least those weapons that might be used in the Yemen conflict.

In 2015, Sweden did not extend a controversial military cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia for reasons concerning human rights violations. In January 2016, the Flemish parliament rejected a request for military equipment supplies to Saudi Arabia, while Germany decided not to sell Leopard tanks to the kingdom and was carefully reviewing all future arms exports to Saudi Arabia because of human rights concerns.

In March 2016, The Netherlands voted to ban weapons exports to Saudi Arabia and in November last year, the Greek parliament's Military Procurements Committee and leading leftist party Syriza mentioned a possibility of halting the arms deal with Saudis worth over €66 million ($80m), saying that Greece would wait for the decisions of the European Parliament and then act accordingly.

|

In all these cases, governments have been facing strong criticism from civil society |  |

The same might be expected in Finland, where all presidential candidates vowed to halt arms sales to the UAE if elected, after images appeared showing the UAE using Finnish-made weapons in Yemen's civil war.

Interestingly, such a possibility has not been mentioned with regards Saudi Arabia - which is also a buyer of Finnish-made weapons.

Giorgio Beretta, an author and arms trade analyst at Italy's Controll Armi, noted that in all these cases, governments have been facing strong criticism from civil society over selling arms to Saudi Arabia and the Emirates. Criticism over arms exports has been loud in other EU countries as well, but with evidently less success.

There have been diverging trends across the EU member states. While some countries, like those mentioned above, have strongly reduced their arms sales to the Gulf, others have profited strongly from the increasing arms demand in the region. Arms exports from the UK and France have risen considerably in the past couple of years.

Can Germany influence other EU states?

Before Germany's recent decision, Angela Merkel's administration had been heavily criticised for massively increasing arms sales to Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

In November 2017, Germany's Economy Ministry was forced to disclose information about the country's arms sales to the two countries, after a request made by several members of the parliament from the Left party. Deutsche Welle reported that the German government approved arms sales of almost €450 million ($526 million) in the third quarter of 2017 alone, almost five times more than in the same quarter a year before.

But after Germany's and Norway's decision to ban arms sales, many are wondering whether some other European states will follow their example - especially the largest European arms dealers in London and Paris.

Although Germany's decision is very relevant, it might not influence other countries, Beretta noted. Marcus Bickel, a veteran reporter at Weltreporter.net and a former Middle East correspondent for Spiegel Online, Die Zeit, and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, says France has been on a selling spree in the Gulf and Egypt - ever since the final years of Hollande.

"[The] French arms industry is much more state-influenced and will not follow the German example," he told The New Arab. "Because it's not in the government's agenda in Paris to stop spreading French arms around the globe."

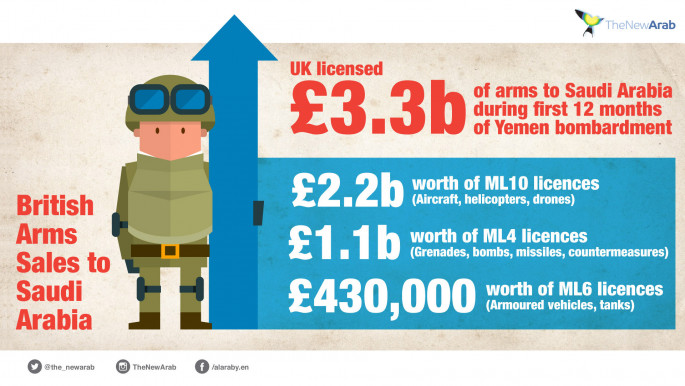

The same goes for the UK, which has never agreed to common European foreign policy goals - and surely never engaged in restrictions on arms sales. After all, in both countries, exports to Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states represent 50 percent or more of total arms exports.

|

Therefore, the perceived economic and political benefits of continuing the arms trade with the Gulf are clearly too significant to abandon over principles.

Nevertheless, Beretta thinks the new German government could decide to raise the question with some European countries or even at EU level. In so doing, Germany would have support not only from its own civil society but also from that of various European countries - making it more difficult for governments such as those of France, the UK and also Italy, to continue exporting all kinds of weapons to Saudi Arabia and UAE.

A decision like that would show that the new German government is serious and determined to set clear priorities in questions concerning international stability, peace and security.

But Bickel says that Germany's decision may not last long. The coalition talks between CDU and SPD, which pushed the move towards more arms export restrictions have just begun. "And not only from CDU, but also inside the Social Democrats, a generation-long conflict is arising: What is an export industry worth if workers in the arms industry in poor Eastern German elections districts lose the few jobs there are?"

Therefore, the powerful arms industry's next move should be closely monitored in terms of how it will navigate around the new decree by the government - if you can call it this at all, taking in account the secrecy of the Bundessicherheitsrat's (Federal Security Council) decisions.

|

Europe cannot tolerate grave violations of human rights and of humanitarian law |  |

Despite the argument that Western countries' arms sales have been key factors prolonging the Yemen war becoming ever louder, more than a dozen European Union states are selling arms or military equipment to Saudi Arabia, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

It is obvious that EU members have deep disagreements about where the international law comes down with respect to arms sales to Riyadh and Abu Dhabi amid the Yemen war.

The European Parliament has called for an EU arms embargo several times in the past two years. For the first time in 2016 when adopting the resolution (2016/2515(RSP)) on the situation in Yemen, which was approved by a large majority of parliament. Since then, the European Parliament has adopted three more documents on this matter: on 15 June 2017 in Strasbourg - Resolution on the Humanitarian situation in Yemen, (2017/2727(RSP)), on 13 September 2017 - Resolution on Arms export: implementation of Common Position 2008/944/CFSP and finally on 30 November 2017 - Resolution on Situation in Yemen (2017/2849(RSP)).

According to Beretta, particularly relevant is the one from September 13, because it is a resolution on the implementation of the Common Position on EU Arms Export (not only, then, on Yemen) but it uses the Yemen case to clearly specify that "[arms] exports to Saudi Arabia are non-compliant with at least Criterion 2 regarding the country's involvement in grave breaches of humanitarian law as established by competent UN authorities" and therefore "re-iterates its call from 26 February 2016 on the urgent need to impose an arms embargo on Saudi Arabia".

So far none of these calls, addressed to the EU Council, resulted in any action by the Council, and it is most unlikely that this time will be any different. Only the European Council (which represents the 28 EU member states) can adopt a European arms embargo, but this decision has to be made unanimously.

Dr Diederik Cops, a researcher at the Belgium-based Flemish Peace Institute and an expert on international conventional arms transfers, is quite sure that because of the different perspectives of EU member states towards Saudi-Arabia in their foreign policies, and with different economic implications of arms sales to that country, a binding EU arms embargo is highly unlikely.

The call for it therefore only has symbolic meaning. Moreover, Bickel notes that the anti-arms-lobby in Brussels is only in the making, whereas the wider European military-industry complex is well settled. The worldwide trend, unfortunately, points in a different direction: more arms sales to more violent and autocratic countries.

So one may argue that, in this moment, an arms embargo is not a realistic option. Yet, Berreta thinks that a strong message should be given: "Europe cannot tolerate grave violations of human rights and of humanitarian law. The European Council should then find a way to adopt, if not an arms embargo, at least a temporary suspension on arms export to all countries involved in the conflict in Yemen. Such a measure could help Europe to have a reliable - and stronger - voice in the peace process for Yemen."

But as always, it would be wrong to assume that EU speaks with a single voice.

Stasa Salacanin is a freelance journalist who has written extensively on Middle Eastern affairs, trade and political relations, Syria and Yemen, terrorism and defence.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News