Iran elections 2017: A new direction for foreign policy?

Two spots of bother

Since the beginning of the Arab Spring in 2011, tensions and conflicts in the Middle East have reached multiple boiling points. And as one of the region's key players, Iran's relationship with its Arab neighbours, and most importantly Saudi Arabia, is crucial to understanding these tensions.

As leaked Saudi diplomatic cables revealed, Iranian-Saudi relations have been extremely tense. Last year, these tensions led to the expulsion of Iranian diplomats from Saudi Arabia, and the severing of diplomatic ties following an attack on the Saudi embassy in Tehran.

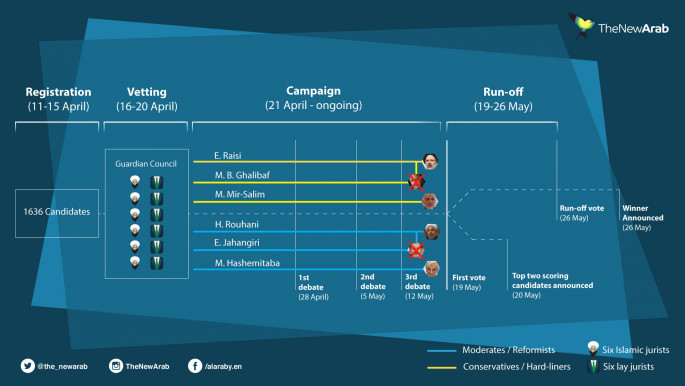

| Read more: A step by step guide to Iran's presidential elections | |

Both countries are now immersed in a cold war, with proxy wars being fought between these two powers in Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Bahrain. These are conflicts that feed on the long-lasting Sunni-Shia divide (far from ideologically driven, this cold war is a geopolitical battle for regional domination between Iran and Saudi Arabia), which now seems more irreconcilable than ever.

Another important development is the signing of the Iran nuclear deal (known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA). Taken together, the JCPOA and the Saudi-Iranian conflict are the prime movers of Iran's future foreign policy. Some observers see these developments as a path leading to hell, whereas others spot a window of opportunity.

Scenario 1: The path to hell

The most serious risk of escalation is posed by the simmering tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Last week's comments by Saudi Defence Minister Mohammed Bin Salman, that there is no space for dialogue between Saudi Arabia and Iran, prompted an aggressive response by Iran's Defense Minister, General Hossein Dehghan. In a war with Saudi Arabia, he said, only Mecca and Medina would be spared from destruction.

Although the long-standing Saudi-Iranian conflict has been largely limited to a series of proxy wars, the Iran nuclear deal has prompted aggressive rhetoric. Israel, the United States and Saudi Arabia have all considered military intervention against Iran to either change the regime or stop the country's nuclear program.

In a famous Wikileaks cable, Saudi Arabia asked the US to "cut the head off the snake" before Iran develops nuclear weapons. Further escalation of the ongoing proxy wars might go in tandem with direct military confrontations between the two countries.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

So what would a full-scale Saudi-Iranian conflict mean for the Middle East? To understand the main areas of conflict one must look at the ethnic-religious map of the region. Conflicts are likely to concentrate either in Sunni countries with a significant Shia minority, or in Shia countries with a significant Sunni minority, which is most countries in the region.

In Iraq, Syria and Yemen, Sunni-Shia conflicts are currently raging, although it is a geopolitical competition between two aspiring regional powers, rather than a religious divide that is at their root. An escalation of the conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran would therefore risk spreading across the entire region.

|

With regards to the JCPOA, a worst-case scenario for Iran's rivals would be a nuclear-armed Iran |  |

The consequences for the Middle East would be dire. Saudi Arabia has the oil money and influence with world powers to cause a lot of damage to Iran. Iran, with a (loose) working alliance with Russia and China, along with an extensive network of proxies throughout the Middle East, can also deal significant damage. For example, Iran has threatened to cut off oil passing through the Strait of Hormuz. This would cause global oil prices to skyrocket and severely damage the global economy.

With regards to the JCPOA, a worst-case scenario for Iran's rivals would be a nuclear-armed Iran. The possibility of this happening isn't entirely unlikely if the region becomes unstable and Iran feels vulnerable. Various important actors in the US, Israel and Saudi Arabia, have claimed the JCPOA could make a nuclear Iran more rather than less likely.

Also, an overt conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia may prompt Iran to withdraw from the JCPOA and even the Non-Proliferation Treaty. This would essentially push Iran's nuclear programme back into the shadows.

| Read more: A who's who of Iran's presidential candidates | |

Generally speaking, support among Iranians for the economic outcomes of the JCPOA has declined. The most recent poll, found that the majority of Iranians haven't experienced the expected improvement in living conditions.

None of the presidential candidates are calling for an open war against Saudi Arabia, or for scrapping the nuclear deal. However, politicians in both the conservative and reformist sides have made clear their willingness to defend Iran to the end.

This is not just a political issue. A portion of the Iranian population (34 percent) supports the development of nuclear power for military use (though this does not necessarily mean becoming a fully fledged nuclear power).

A combination of a hardliner president such as Mir-Salim, paired with an aggressive Saudi-Israeli-USA entente would be an explosive mix, with wide-reaching consequences for the region. One can only hope that the massive economic, human and strategical costs of such a war will serve as a deterrent.

Scenario 2: Same ol’, same ol’

A second, quite plausible scenario, is that things will continue pretty much as they are now: The JCPOA will stay in place; Iran and Saudi Arabia's proxy war in Yemen will continue to be fought mostly within Yemen's borders, and the Iranian and Russian military forces will continue bolstering Bashar Al-Assad in Syria.

In Iraq, IS will eventually be defeated (a goal the US shares), and Iran's economy will continue to improve, albeit at a modest pace if the past is a good indicator; Iran's relationship with Israel and the West will remain fraught but stable.

This continuation doesn't depend only on what Iran wants. If the United States and Israel take a more active role in Syria or Yemen, or if Russia somehow decides to reduce its involvement in the conflict, things could change dramatically.

|

While all candidates have expressed their formal support for the JCPOA, Raisi has said it might require some renegotiation |  |

The Trump administration's foreign policy has been unpredictable, including with regards to Iran. Trump, marred by political conflicts and internal investigations, could be searching for a way to gain the upper hand. The US Senate is currently considering labelling the Iranian Revolutionary Guard a terrorist group, which would further exacerbate US-Iranian tensions.

Barring a radical change, we can expect the Saudi-Iranian proxy conflict to continue more or less as is. At the same time, Iran itself is likely to stay stable. It will continue to gradually increase its influence in Iraq, as General Qasem Soleimani and his Quds Force continue their work. On the whole, diplomacy and a slow rapprochement with the West and Russia will remain on the table.

| Read more: Trump vs the Iran nuclear deal | |

The above scenario is most likely, if incumbent Rouhani is re-elected by a narrow margin, in which case reformists and conservatives would be compelled to compromise. Rouhani isn't likely to unilaterally escalate the current lingering conflicts (for Iran at least) into full-scale war. However, if Mir-Salim, or to a lesser extent Raisi wins, Iran may favour a more hawkish approach.

A narrow victory of incumbent Rouhani seems now the most likely outcome of the election, with the combined conservative candidates polling between 24 percent and 53 percent, and the combined reformist candidates polling between 31 percent and 54 percent.

While all candidates have expressed their formal support for the JCPOA, Raisi has said it might require some renegotiation.

At the same time, domestic tensions in Iran are rising, and a conservative win could reinvigorate the Green Movement. A Raisi victory would be unlikely to cause any immediate, radical shifts in Iranian foreign policy, but over a four year term, the differences could be significant.

Scenario 3: De-escalation

Despite aggressive rhetoric aimed at Iran by both Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu, Trump has stopped short of cancelling the JCPOA, which seemed a sure goner after his electoral victory. In parallel, President Rouhani has adopted a new approach to Iran's international policy that seeks to move away from regionalism to instead exploit the shifting global balance of power.

In this de-escalation scenario, both Iran and Saudi Arabia have their hands partially tied due to their entanglements with shared western commercial partners and allies, resulting in a reduction of tensions.

|

A western-Iranian rapprochement in the region would open the possibility of peaceful resolution of some conflicts |  |

In terms of the JCPOA, Iran is hoping to set the foundations for a much more ambitious goal - ditching its "pariah state" label. The same wish can be seen in Saudi Arabia's tacit alliance with Israel and the United States, which has achieved an extended period of stability and economic growth despite Saudi Arabia's numerous human rights violations.

Iran's goal of following a similar path appears acceptable to the Supreme Leader and some important conservative leaders (despite harsh rhetoric suggesting otherwise).

A western-Iranian rapprochement in the region would open the possibility of peaceful resolution of some conflicts, especially if at least one of the sides sees compromise as a reasonable exit. This could happen, although any such detente will face considerable opposition from Israel and its powerful lobby in the United States.

|

The most important things to most Iranian citizens are an improvement of the economy and security, not foreign entanglements |  |

Although supportive of the nuclear deal, conservative hardliners disagree with abandoning a regionalist view of international politics, and are very uncomfortable with compromising with Saudi Arabia or Israel.

The de-escalation scenario is then most likely in the case of a comfortable victory for the incumbent Rouhani, who in his campaign has already shifted his rhetoric to the Left, and is determined to move Iran away from isolationism and fundamentalism.

While polling data is difficult to come by, it appears that the most important things to most Iranian citizens are an improvement of the economy and security, not foreign entanglements. The vast majority of Iranians, though not necessarily supportive of the theocratic nature of the Iranian regime, oppose a foreign invasion into the country.

Secular Iranians too are wary of foreign intervention. Despite people's differences in religious, moral and social views, America and many other western countries are often unpopular.

Behnam (Ben) Gharagozli received his BA with Highest Distinction in Political Science from UC Berkeley and his JD cum laude from UC Hastings College of the Law. While at UC Hastings, he served as Development Editor of the Hastings International and Comparative Law Review.

Follow him on Twitter: @BenGharagozli

Jon Roozenbeek is a PhD candidate at the Department of Slavonic Studies at the University of Cambridge. He studies Ukraine's media after 2014. Before coming to Cambridge, he worked as a freelance writer, editor and journalist.

Adrià Salvador Palau Is a PhD candidate in the Distributed Information and Automation Laboratory at the University of Cambridge. He has written several journalistic articles about politics and international relations. He is interested in how data science can be used to better understand political dynamics.

Follow him on Twitter: @adriasalvador

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News