Where do Islamic State and al-Qaeda get their explosives?

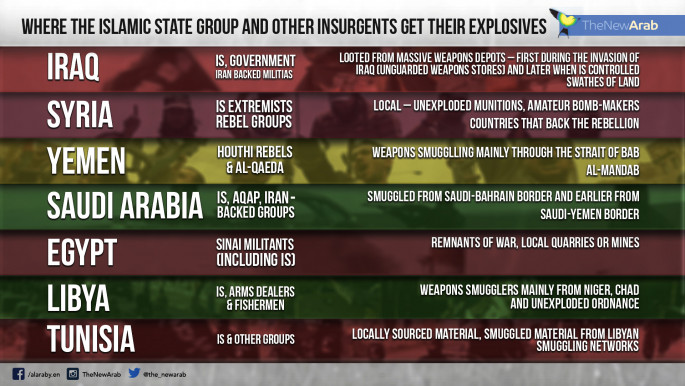

Where do the explosives used by terrorist groups and insurgents that have killed many thousands in the Arab world come from? The New Arab studies seven countries to find out.

14 min read

Rebels have been producing homemade bombs [Anadolu]

Islamic State group militants, al-Qaeda, Houthi rebels and other insurgents seem to have nearly unfettered access to a huge amount of explosives and bomb-making material.

Bombs such as improvised explosive devices (IEDs), car bombs and landmines have killed or injured hundreds of thousands of people in many Arab countries. Most devices are homemade with locally sourced material, or smuggled through increasingly porous borders.

But from where do they get them, how do they make them, how can they afford them, and who manufactures them?

In an exclusive investigation, The New Arab has studied militant groups in seven Arab countries.

The 'terrorist goldmine' in Iraq

Asaad al-Jubouri, a retired general in the Iraqi army, insists on calling the country's military weapons and ammunition depots "the terrorist goldmine".

Jubouri told The New Arab that dozens of military sites around Iraq, containing huge amounts of raw material used for making explosives, were looted in two phases. The deadly contents are now used both by the Islamic State group and government-backed Shia armed groups, such as the Hashd al-Shaabi Popular Mobilisation militia.

Hundreds of tons of powerful explosives and bomb-making material were looted from unguarded weapons sites following the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. They were later used in successive waves of attacks against Iraqi civilians and US soldiers.

Years later, IS militants looted what had become one of the world's largest military arsenals not subject to governmental authority or any other regular military force when the group took control of Mosul, Ramadi and other areas in northern Iraq.

Weapons stockpiles in Rashid, Taji, Habbaniyah, Abu Ghraib, Balad and Ghazlani military camps had contained tons of ammunition for tanks, as well as anti-aircraft guns, mortars, shoulder-launched missiles, Katyusha rockets and mines.

Those depots were left empty by the Islamic State group as it swept through its lightning offensive in June 2014.

Factories and bomb-making facilities containing research and information about manufacturing bombs and huge amounts of highly explosive material were also looted.

Jubouri said that the stolen military arsenal is used by militias and armed groups in two ways:

Direct use: This applies to mines, shoulder-launched missiles, mortars and guns.

Indirect use: Using ammunition from tanks and mortars, for example, to make car bombs, suicide belts and IEDs, adding other material to them, or changing the way they work.

Major Naim Maksousi, an explosives expert in the Iraqi ministry of defence, told The New Arab most explosives used in Iraq were locally manufactured using material from ammunition looted from army depots.

Most common is the use of anti-aircraft, tank, or mortar shells, due to their large explosives capacity and charge. They are either detonated using cables or a mobile phone.

Oxygen bottles filled with TNT tend to be used against heavy targets such as tanks, armoured vehicles, and mine sweepers.

Militant groups also use pesticides and fertilisers that they mix with TNT or C4 and nails or ball-bearings. These are mainly used in car bombs to produce highly damaging shrapnel explosions that maim and seriously injure as many as they kill.

The favourite bombs of Syria's insurgents

As the Syrian rebellion against the regime of Bashar al-Assad became increasingly militarised, Syria's rebels - as well as jihadists who later entered the fray - needed a lot of firepower to cope with the war machine of the Syrian government and its allied militias.

Initially, the Syrian opposition used primitive bombs and munitions made from fertiliser and other raw material easily available in Syria. The know-how of the opposition began to evolve and the rebels soon began producing more sophisticated mines, shells, rockets and explosive devices.

Syria's amateur bomb-makers had to learn on the job, but slowly became a force to be reckoned with.

One was a young Syrian we identify here by his initials MNO.

MNO, initially an amateur weapons and explosives enthusiast, is credited with the invention of the most formidable improvised weapon in the hands of the Syrian opposition, the so called Jahannam ["hell"] cannon, which fires household gas bottles repurposed as rockets - though the weapon is indiscriminate and has reportedly often resulted in civilian casualties.

MNO told The New Arab he does not belong to any one faction, but offers his services to Syrian opposition groups that need them.

He said one problem he faced during the battle for Taftanaz airport in Idlib was how to deliver explosive devices into the airbase from a distance.

This is where the idea of the flying gas bottles came to him.

The gas bottles are modified using fins and heads that explode on impact.

His first experiments saw him load the heads with fertiliser-based explosives, before later adapting to TNT. They are fired using the Jahannam cannon.

MNO lost parts of his right hand while experimenting with explosives, which he said do not cost much (a bag of fertiliser costs $50 and is enough to make 10 explosive devices, while the cannon itself is made from scrap using simple lathe machines).

The rebels in Aleppo have also worked with pharmacists to make crude mines used to detonate Syrian army armour, using basic raw materials, according to Free Syrian Army explosives expert Ali Hassoun.

Electrical engineers, meanwhile, help make the circuits needed to control the launch of crude rockets, detonators, and remote detonators.

The Syrian rebels say that things changed after 2013, with the entry of TNT to Syria from countries that back the rebellion. Ali Hassoun said the rebels also scavenge explosive material from unexploded rockets and bombs fired by the regime.

This allowed the rebels to attack heavily armoured tanks - such as the Russian-made T72 - using improvised mines, after mixing TNT with motor oil.

The Syrian rebels have the ability to detonate these devices remotely, using detonators with a range of more than a kilometre, said Hassoun.

But perhaps the most dangerous type of explosive in use by insurgents in Syria is C4, according to FSA officer Abu al-Alaa.

C4 has much greater destructive power than even TNT.

C4, he continued, is mostly used in assassinations and in the making of suicide vests worn by Islamic State group militants.

Abu al-Alaa stressed the FSA had never used C4, which he said had not been supplied to rebel factions by their international backers.

By contrast, IS has used C4 to target rebel commanders, including FSA leaders.

Nevertheless, some factions were able to obtain C4 from smugglers. They have used it in car bombs targeting regime installations as well as suicide belts, and "sticky bombs", which can be affixed to targets using magnets and then detonated remotely.

"C4 has a bad reputation, and we do not have precise information regarding the quantity of C4 in circulation in Syria," Abu al-Alaa told The New Arab.

Ammonium nitrate: The deadly ingredient killing Tunisians

Badra Gaaloul, the director of the International Centre for Strategic and Security Studies in Tunisia, believes her country is no longer safe from terrorist attacks after a vast cache of weapons and explosives was discovered by Tunisian officials.

"Authorities have announced the discovery of 15 caches so far, however there is no telling the real number of weapons and explosives in Tunisia," said Gaaloul.

"Terrorists have not used all their weapons and explosives stockpiles and they are working on smuggling more from Libya."

A November 2013 International Crisis Group report warned of the increased smuggling activities taking place on Tunisia's borders - especially the frontier shared with Libya, through which arms, oil and explosives are flowing into the country.

Tunisian authorities recently uncovered smuggling networks providing material and logistical support to armed groups, transferring weapons and explosives into Tunisia through its 500km border with Libya.

Most recent attacks in Tunisia have been carried out by IS, but Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has also carried out several deadly attacks on security forces over the past four years - particularly in the mountainous Jebel ech-Chaambi region near the Algerian border.

Another group, Ansar al-Sharia, has been accused of attacking the US embassy in Tunis in September 2012.

Retired Colonel Mohammad Saleh al-Hadri told The New Arab that armed groups used the chaos that followed the Tunisian revolution to smuggle vast amounts of explosives and bomb-making material into the country.

"Most of the terrorist attacks that took place in the Jebel ech-Chaambi region during the revolution used homemade explosives. The explosives were made with ammonium nitrate which is used as a fertiliser," said Hadri.

Hadri added that ammonium nitrate from Tunisia had also likely been smuggled to jihadist groups in Senegal and Mali.

Armed groups also use locally available material such as potassium nitrate and other fertilisers to produce bombs using instruction manuals posted on jihadist internet forums that teach bomb-making.

Yemen's woes

In December 2015, an Islamic State group car bomb targeted the motorcade of the governor of Aden, killing him and a number of his guards.

A few weeks earlier, multiple car bombs targeted the temporary headquarters of the Yemeni government in Aden and the Saudi-led coalition's command centre.

Car bombs, IEDs and explosive belts are the "deadliest weapons in the arsenal of terrorists in Yemen", according to Anwar Mahmoud, a Yemeni security officer.

Another officer, Abdel Salam Khaled [not his real name], said these explosives are mostly made from fireworks, fertilisers and pesticides, which were heavily smuggled into the country between 2013 and 2014.

They are used by groups such as Al-Qaeda and Houthi rebels, he said.

The New Arab obtained data that shows 80 percent of the smuggled materials seized by Yemeni security forces between 2013 and 2014 were fertilisers and pesticides used to make explosives.

However, Sultan Mohammad, an officer who served in Bab al-Mandab, the most important point of entry for smuggled goods into Yemen, believes that the true scale of smuggling is far greater than government figures suggest.

Mohammad's assessment is supported by a 2013 ministry of agriculture report that stated smuggled fertilisers and pesticides were estimated to amount to dozens of tons each year.

A 2014 report by the ministry said that only a quarter of Yemen's 2,500 to 3,000-ton pesticide needs were being imported through legitimate means, which means the rest was coming into the country through illicit smuggling routes.

Mohammad al-Salwi, chief chemist at the University of Sanaa laboratories, told The New Arab that while bomb-making materials remain easy to come by, they require experienced people to manufacture them, in addition to local knowledge.

Meanwhile, groups such as the Houthi rebels have not only used homemade explosives with locally sourced material but have also been able to obtain ready-made military grade explosives through their alliance with army troops loyal to deposed president Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Saudi Arabia's sources

On the bridge connecting Saudi Arabia with Bahrain, Abdullah al-Assairi, a Saudi customs officer, pulls over a car that arouses his suspicions.

Helped by trained police dogs, almost an hour passes as he thoroughly searches the car. Soon after, Assairi is reporting the car to one of his senior officers, forwarding a report about the two men inside.

There may be nothing to worry about, but Assairi would rather deal with angry travellers for a few hours than allow the import of prohibited articles into his country.

"We are not talking about drugs, but what is more dangerous," Assairi told us. "I mean explosives, which terrorists are trying to smuggle across the borders into the country."

Assairi's suspicions may be justified. The smuggling of explosives across Saudi Arabia's land and maritime borders seems on the increase.

Latest reports from Saudi customs confirm that the total amount of explosives confiscated in 2014 saw a 67 percent increase from the previous year. Security experts expect a 250 percent rise for 2015 following major seizures on the Saudi-Bahraini border.

Last year on 6 May, Saudi security forces along with their Bahraini counterparts foiled an attempt to smuggle more than 30kg of the highly explosive 'RDX' material, according to a statement from the Saudi Interior Ministry.

Five smugglers were arrested and bomb-making manuals were found in their possession, along with documents relating to military patrols, Iranian SIM cards, and currency from Saudi Arabia, Iran and Jordan.

The following month, on June 16, Bahraini police announced the recovery of explosives intended for use in attacks on Saudi Arabia and Bahrain.

Former brigadier-general Ali Hassan al-Rashed told The New Arab that RDX - an abbreviation of Research Department Explosive - is a highly explosive substance that is impossible to manufacture locally as it is both very expensive and delicate.

"Terrorists prefer using C4 and RDX because they are highly explosive and very powerful," said Saudi terrorism expert Munif al-Safouki. "They are easily transported and can be used in small quantities, unlike conventional explosives."

Ahmad Mowakili, a specialist in the analysis of terrorist organisations, told The New Arab that groups were now working to increase the explosive force of RDX by combining it with metals.

Youssef Rumaih, a professor of crime control in Saudi Arabia, blamed groups reportedly affiliated with Iran for allegedly trying to bring RDX into Saudi Arabia.

"We do not say that in vain," Rumaih told The New Arab. "A number of foiled smuggling attempts took place in May and June last year, and all had come from Iran, carrying the same type of RDX explosive."

Munif al-Safouki agreed that Saudi fears of smuggled explosives from Iran were not exaggerated.

"A number of attempts by Iran-backed groups to smuggle RDX explosives were foiled in Iraq and Bahrain," Safouki told The New Arab.

Security expert Sultan al-Ubthani also said that the production and smuggling of explosives into Saudi Arabia was not restricted merely to the past two years.

"Smugglers would have previously used the Yemen-Saudi border," Ubthani told The New Arab.

"The first terrorist operation in Saudi Arabia took place in 1997, using explosives that were smuggled through the Yemen-Saudi border, according to Saudi security services."

In recent months, smuggling through the Yemeni border decreased because of the war in Yemen that led to the border coming under tighter control, Ubthani claimed.

It seems, as a consequence, smugglers have instead resorted to maritime channels to bring in prohibited articles into Saudi Arabia, as the Gulf coast is harder to control than the country's land borders.

Saudi security sources further claimed that most attempts to smuggle explosives across the border had been foiled.

Explosive Egypt

"The people of Sinai recite the declaration of faith with every step they take in case it will be the last one," said Salim Abu Fraij, a Sinai resident who lost his right leg when his car drove over an improvised explosive device (IED) planted by militants in north-east Sinai.

IEDs have become the weapon of choice for militant groups operating in Sinai, where they are primarily used to target Egyptian security forces.

ANFO - an industrial explosive mixture - along with TNT, C4, nitroglycerin and potassium nitrate are among the components used by Sinai militants to make IEDs.

Militant groups procure these materials in a number of ways, including the collection of remnants of war and through the various quarries that exist in the Sinai mountains that produce materials such as iron oxide and potassium nitrate.

Colonel Ahmed Abdel Salam, the head of the explosives unit at the northern Sinai security force, told The New Arab that most IEDs there had used rudimentary materials such as agricultural fertilisers.

Abdel Salam said militants had developed methods to make the explosives more powerful and incendiary by adding wood shavings to the explosive mixtures, making the IEDs cheap to produce and very deadly.

Such explosives have so far killed 352 police officers and 487 soldiers, in addition to injuring 1,389 people since 30 June 2013, according to a report by the Egyptian foreign minister published in September 2015.

Major-General Mustafa al-Razzazz of the north Sinai security force said that security forces had begun taking precautionary measures such as uprooting trees that line roads, increasing checkpoints and reinforcing security vehicles to protect against IEDs.

Libya killer

Bombs such as improvised explosive devices (IEDs), car bombs and landmines have killed or injured hundreds of thousands of people in many Arab countries. Most devices are homemade with locally sourced material, or smuggled through increasingly porous borders.

But from where do they get them, how do they make them, how can they afford them, and who manufactures them?

In an exclusive investigation, The New Arab has studied militant groups in seven Arab countries.

The 'terrorist goldmine' in Iraq

Asaad al-Jubouri, a retired general in the Iraqi army, insists on calling the country's military weapons and ammunition depots "the terrorist goldmine".

Jubouri told The New Arab that dozens of military sites around Iraq, containing huge amounts of raw material used for making explosives, were looted in two phases. The deadly contents are now used both by the Islamic State group and government-backed Shia armed groups, such as the Hashd al-Shaabi Popular Mobilisation militia.

Hundreds of tons of powerful explosives and bomb-making material were looted from unguarded weapons sites following the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. They were later used in successive waves of attacks against Iraqi civilians and US soldiers.

Years later, IS militants looted what had become one of the world's largest military arsenals not subject to governmental authority or any other regular military force when the group took control of Mosul, Ramadi and other areas in northern Iraq.

Weapons stockpiles in Rashid, Taji, Habbaniyah, Abu Ghraib, Balad and Ghazlani military camps had contained tons of ammunition for tanks, as well as anti-aircraft guns, mortars, shoulder-launched missiles, Katyusha rockets and mines.

Those depots were left empty by the Islamic State group as it swept through its lightning offensive in June 2014.

Factories and bomb-making facilities containing research and information about manufacturing bombs and huge amounts of highly explosive material were also looted.

|

|

|

Bombings have taken a huge toll on Iraq, both in the |

Jubouri said that the stolen military arsenal is used by militias and armed groups in two ways:

Direct use: This applies to mines, shoulder-launched missiles, mortars and guns.

Indirect use: Using ammunition from tanks and mortars, for example, to make car bombs, suicide belts and IEDs, adding other material to them, or changing the way they work.

|

Oxygen bottles filled with TNT explosives are usually used against heavy targets like tanks, armoured vehicles, and mine sweepers |  |

Major Naim Maksousi, an explosives expert in the Iraqi ministry of defence, told The New Arab most explosives used in Iraq were locally manufactured using material from ammunition looted from army depots.

Most common is the use of anti-aircraft, tank, or mortar shells, due to their large explosives capacity and charge. They are either detonated using cables or a mobile phone.

Oxygen bottles filled with TNT tend to be used against heavy targets such as tanks, armoured vehicles, and mine sweepers.

Militant groups also use pesticides and fertilisers that they mix with TNT or C4 and nails or ball-bearings. These are mainly used in car bombs to produce highly damaging shrapnel explosions that maim and seriously injure as many as they kill.

The favourite bombs of Syria's insurgents

As the Syrian rebellion against the regime of Bashar al-Assad became increasingly militarised, Syria's rebels - as well as jihadists who later entered the fray - needed a lot of firepower to cope with the war machine of the Syrian government and its allied militias.

Initially, the Syrian opposition used primitive bombs and munitions made from fertiliser and other raw material easily available in Syria. The know-how of the opposition began to evolve and the rebels soon began producing more sophisticated mines, shells, rockets and explosive devices.

Syria's amateur bomb-makers had to learn on the job, but slowly became a force to be reckoned with.

One was a young Syrian we identify here by his initials MNO.

MNO, initially an amateur weapons and explosives enthusiast, is credited with the invention of the most formidable improvised weapon in the hands of the Syrian opposition, the so called Jahannam ["hell"] cannon, which fires household gas bottles repurposed as rockets - though the weapon is indiscriminate and has reportedly often resulted in civilian casualties.

MNO told The New Arab he does not belong to any one faction, but offers his services to Syrian opposition groups that need them.

|

|

| MNO's Jahannam (hell) cannon being used in Aleppo, Syria, in December 2014 [Anadolu] |

He said one problem he faced during the battle for Taftanaz airport in Idlib was how to deliver explosive devices into the airbase from a distance.

This is where the idea of the flying gas bottles came to him.

The gas bottles are modified using fins and heads that explode on impact.

His first experiments saw him load the heads with fertiliser-based explosives, before later adapting to TNT. They are fired using the Jahannam cannon.

MNO lost parts of his right hand while experimenting with explosives, which he said do not cost much (a bag of fertiliser costs $50 and is enough to make 10 explosive devices, while the cannon itself is made from scrap using simple lathe machines).

|

|

| The Jahannam has been used extensively by rebel groups near Aleppo [Anadolu] |

The rebels in Aleppo have also worked with pharmacists to make crude mines used to detonate Syrian army armour, using basic raw materials, according to Free Syrian Army explosives expert Ali Hassoun.

Electrical engineers, meanwhile, help make the circuits needed to control the launch of crude rockets, detonators, and remote detonators.

The Syrian rebels say that things changed after 2013, with the entry of TNT to Syria from countries that back the rebellion. Ali Hassoun said the rebels also scavenge explosive material from unexploded rockets and bombs fired by the regime.

This allowed the rebels to attack heavily armoured tanks - such as the Russian-made T72 - using improvised mines, after mixing TNT with motor oil.

The Syrian rebels have the ability to detonate these devices remotely, using detonators with a range of more than a kilometre, said Hassoun.

But perhaps the most dangerous type of explosive in use by insurgents in Syria is C4, according to FSA officer Abu al-Alaa.

C4 has much greater destructive power than even TNT.

|

|

| A rebel fighter places explosive packets into a suicide belt to be detonated using the orange fuses (R), in Raqqa, Syria, on 5 August, 2013 [AFP] |

C4, he continued, is mostly used in assassinations and in the making of suicide vests worn by Islamic State group militants.

Abu al-Alaa stressed the FSA had never used C4, which he said had not been supplied to rebel factions by their international backers.

By contrast, IS has used C4 to target rebel commanders, including FSA leaders.

Nevertheless, some factions were able to obtain C4 from smugglers. They have used it in car bombs targeting regime installations as well as suicide belts, and "sticky bombs", which can be affixed to targets using magnets and then detonated remotely.

"C4 has a bad reputation, and we do not have precise information regarding the quantity of C4 in circulation in Syria," Abu al-Alaa told The New Arab.

Ammonium nitrate: The deadly ingredient killing Tunisians

Badra Gaaloul, the director of the International Centre for Strategic and Security Studies in Tunisia, believes her country is no longer safe from terrorist attacks after a vast cache of weapons and explosives was discovered by Tunisian officials.

"Authorities have announced the discovery of 15 caches so far, however there is no telling the real number of weapons and explosives in Tunisia," said Gaaloul.

|

Terrorists have not used all their weapons and explosives stockpiles and they are working on smuggling more from Libya - Director of the International Centre for Strategic and Security Studies in Tunisia |

|

"Terrorists have not used all their weapons and explosives stockpiles and they are working on smuggling more from Libya."

A November 2013 International Crisis Group report warned of the increased smuggling activities taking place on Tunisia's borders - especially the frontier shared with Libya, through which arms, oil and explosives are flowing into the country.

Tunisian authorities recently uncovered smuggling networks providing material and logistical support to armed groups, transferring weapons and explosives into Tunisia through its 500km border with Libya.

Most recent attacks in Tunisia have been carried out by IS, but Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has also carried out several deadly attacks on security forces over the past four years - particularly in the mountainous Jebel ech-Chaambi region near the Algerian border.

Another group, Ansar al-Sharia, has been accused of attacking the US embassy in Tunis in September 2012.

Retired Colonel Mohammad Saleh al-Hadri told The New Arab that armed groups used the chaos that followed the Tunisian revolution to smuggle vast amounts of explosives and bomb-making material into the country.

"Most of the terrorist attacks that took place in the Jebel ech-Chaambi region during the revolution used homemade explosives. The explosives were made with ammonium nitrate which is used as a fertiliser," said Hadri.

Hadri added that ammonium nitrate from Tunisia had also likely been smuggled to jihadist groups in Senegal and Mali.

Armed groups also use locally available material such as potassium nitrate and other fertilisers to produce bombs using instruction manuals posted on jihadist internet forums that teach bomb-making.

Yemen's woes

In December 2015, an Islamic State group car bomb targeted the motorcade of the governor of Aden, killing him and a number of his guards.

A few weeks earlier, multiple car bombs targeted the temporary headquarters of the Yemeni government in Aden and the Saudi-led coalition's command centre.

|

80 percent of the smuggled materials seized by Yemeni security forces between 2013 and 2014 were fertilisers and pesticides |  |

Car bombs, IEDs and explosive belts are the "deadliest weapons in the arsenal of terrorists in Yemen", according to Anwar Mahmoud, a Yemeni security officer.

|

|

| The new governor of Aden survived a car bomb attack in January 2016 [Anadolu] |

Another officer, Abdel Salam Khaled [not his real name], said these explosives are mostly made from fireworks, fertilisers and pesticides, which were heavily smuggled into the country between 2013 and 2014.

They are used by groups such as Al-Qaeda and Houthi rebels, he said.

The New Arab obtained data that shows 80 percent of the smuggled materials seized by Yemeni security forces between 2013 and 2014 were fertilisers and pesticides used to make explosives.

However, Sultan Mohammad, an officer who served in Bab al-Mandab, the most important point of entry for smuggled goods into Yemen, believes that the true scale of smuggling is far greater than government figures suggest.

Mohammad's assessment is supported by a 2013 ministry of agriculture report that stated smuggled fertilisers and pesticides were estimated to amount to dozens of tons each year.

A 2014 report by the ministry said that only a quarter of Yemen's 2,500 to 3,000-ton pesticide needs were being imported through legitimate means, which means the rest was coming into the country through illicit smuggling routes.

Mohammad al-Salwi, chief chemist at the University of Sanaa laboratories, told The New Arab that while bomb-making materials remain easy to come by, they require experienced people to manufacture them, in addition to local knowledge.

Meanwhile, groups such as the Houthi rebels have not only used homemade explosives with locally sourced material but have also been able to obtain ready-made military grade explosives through their alliance with army troops loyal to deposed president Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Saudi Arabia's sources

On the bridge connecting Saudi Arabia with Bahrain, Abdullah al-Assairi, a Saudi customs officer, pulls over a car that arouses his suspicions.

Helped by trained police dogs, almost an hour passes as he thoroughly searches the car. Soon after, Assairi is reporting the car to one of his senior officers, forwarding a report about the two men inside.

There may be nothing to worry about, but Assairi would rather deal with angry travellers for a few hours than allow the import of prohibited articles into his country.

"We are not talking about drugs, but what is more dangerous," Assairi told us. "I mean explosives, which terrorists are trying to smuggle across the borders into the country."

Assairi's suspicions may be justified. The smuggling of explosives across Saudi Arabia's land and maritime borders seems on the increase.

|

Terrorists prefer using C4 and RDX because they are highly explosive and very powerful - Saudi terrorism expert |

|

Latest reports from Saudi customs confirm that the total amount of explosives confiscated in 2014 saw a 67 percent increase from the previous year. Security experts expect a 250 percent rise for 2015 following major seizures on the Saudi-Bahraini border.

Last year on 6 May, Saudi security forces along with their Bahraini counterparts foiled an attempt to smuggle more than 30kg of the highly explosive 'RDX' material, according to a statement from the Saudi Interior Ministry.

Five smugglers were arrested and bomb-making manuals were found in their possession, along with documents relating to military patrols, Iranian SIM cards, and currency from Saudi Arabia, Iran and Jordan.

The following month, on June 16, Bahraini police announced the recovery of explosives intended for use in attacks on Saudi Arabia and Bahrain.

Former brigadier-general Ali Hassan al-Rashed told The New Arab that RDX - an abbreviation of Research Department Explosive - is a highly explosive substance that is impossible to manufacture locally as it is both very expensive and delicate.

"Terrorists prefer using C4 and RDX because they are highly explosive and very powerful," said Saudi terrorism expert Munif al-Safouki. "They are easily transported and can be used in small quantities, unlike conventional explosives."

Ahmad Mowakili, a specialist in the analysis of terrorist organisations, told The New Arab that groups were now working to increase the explosive force of RDX by combining it with metals.

Youssef Rumaih, a professor of crime control in Saudi Arabia, blamed groups reportedly affiliated with Iran for allegedly trying to bring RDX into Saudi Arabia.

"We do not say that in vain," Rumaih told The New Arab. "A number of foiled smuggling attempts took place in May and June last year, and all had come from Iran, carrying the same type of RDX explosive."

Munif al-Safouki agreed that Saudi fears of smuggled explosives from Iran were not exaggerated.

"A number of attempts by Iran-backed groups to smuggle RDX explosives were foiled in Iraq and Bahrain," Safouki told The New Arab.

|

Smuggling through the Yemeni border decreased because of the war in Yemen |  |

Security expert Sultan al-Ubthani also said that the production and smuggling of explosives into Saudi Arabia was not restricted merely to the past two years.

"Smugglers would have previously used the Yemen-Saudi border," Ubthani told The New Arab.

"The first terrorist operation in Saudi Arabia took place in 1997, using explosives that were smuggled through the Yemen-Saudi border, according to Saudi security services."

|

|

| Riyadh's war in Yemen has cut down on weapons smuggling, officials claim [Getty] |

In recent months, smuggling through the Yemeni border decreased because of the war in Yemen that led to the border coming under tighter control, Ubthani claimed.

It seems, as a consequence, smugglers have instead resorted to maritime channels to bring in prohibited articles into Saudi Arabia, as the Gulf coast is harder to control than the country's land borders.

Saudi security sources further claimed that most attempts to smuggle explosives across the border had been foiled.

Explosive Egypt

"The people of Sinai recite the declaration of faith with every step they take in case it will be the last one," said Salim Abu Fraij, a Sinai resident who lost his right leg when his car drove over an improvised explosive device (IED) planted by militants in north-east Sinai.

IEDs have become the weapon of choice for militant groups operating in Sinai, where they are primarily used to target Egyptian security forces.

ANFO - an industrial explosive mixture - along with TNT, C4, nitroglycerin and potassium nitrate are among the components used by Sinai militants to make IEDs.

|

The people of Sinai recite the declaration of faith with every step they take - Sinai victim of an IED |

|

Militant groups procure these materials in a number of ways, including the collection of remnants of war and through the various quarries that exist in the Sinai mountains that produce materials such as iron oxide and potassium nitrate.

Colonel Ahmed Abdel Salam, the head of the explosives unit at the northern Sinai security force, told The New Arab that most IEDs there had used rudimentary materials such as agricultural fertilisers.

Abdel Salam said militants had developed methods to make the explosives more powerful and incendiary by adding wood shavings to the explosive mixtures, making the IEDs cheap to produce and very deadly.

Such explosives have so far killed 352 police officers and 487 soldiers, in addition to injuring 1,389 people since 30 June 2013, according to a report by the Egyptian foreign minister published in September 2015.

Major-General Mustafa al-Razzazz of the north Sinai security force said that security forces had begun taking precautionary measures such as uprooting trees that line roads, increasing checkpoints and reinforcing security vehicles to protect against IEDs.

Libya killer

Car bombs, improvised explosive devices and explosive belts have become the most common killers in Libya since the country's revolution against the Gaddafi regime in 2011.

In the absence of official reports on the number of victims, Libyan civil society groups estimate that explosive devices killed 2,800 Libyans in 2014.

Colonel Youssef Dowah, a former national security adviser to the Libyan government, believes that explosives are very easy to come by, at cheap prices, given Libya's open borders with Niger and Chad frequented by smugglers.

Additionally, the country has large amounts of unexploded ordnance used by criminal and extremist groups.

|

Even the country's fishermen are repurposing unexploded ordnance into homemade TNT |  |

Even the country's fishermen are repurposing these unexploded ordnance into homemade TNT, which has led to a depletion of local fish stocks due to the use of military grade explosives.

|

|

| Unexploded munitions are gathered and destroyed by the Military College of Engineering in Misrata before they can be adapted by armed groups [Anadolu] |

In the city of Misrata alone, Handicap International's clearance teams cleared 3,689 rockets, 8,523 mortar rounds, 75,369 explosive projectiles, 82 hand grenades, 7,521 detonators and 74 landmines - in 2014 alone.

Mistrata is considered to be one of the few Libyan cities that transparently collect and dispose of unexploded ordnance, according to Suhaib Salah, a local volunteer with DanChurchAid, an international charity that works on clearing mines and explosive remnants of war.

In other cities, it is common for the collected explosives and munitions to be sold to arms dealers and a variety of armed groups to be reused.

The widespread availability of explosive materials in Libya has made it an exporter of bomb-making materials to extremist groups in neighbouring countries.

Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt and Sudan have all announced the confscation of explosive materials at their borders with Libya.

Follow us on Twitter: @The_NewArab

|

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News