Poisoned minds and a poisoned sky: The IS legacy

Qayyara, northern Iraq. A group of children play football, some of their friends sit on long concrete pipes. They laugh and throw bolts, competing to see who lobs further.

It sounds like a scene of calm daily life in a city that was regained by the Iraqi army three months ago from the ravages of the Islamic State group.

But looking at them closely, the children have their hands and feet blackened, their faces smeared with soot.

They are breathing smoke and sulphur.

They are free to play football, but play downwind of oil wells set alight by IS miltants three months ago.

The oil wells are still burning.

In the early summer, IS, in an attempt to slow the Iraqi army's advance, set fire to at least a dozen of the city's oil wells, according to the United Nations, In September and October, they launched at least three chemical attacks, setting fires at the chemical plant in Mishraq, south of Mosul.

They left in their wake the results of two years of terror and violence - and an environmental disaster that is damaging the health of the whole population here.

Zyad works at shutting down the oil wells.

"Today in Qayyara everything is lacking," he says. "In the hospital, even oxygen to treat those who have respiratory difficulties is lacking.

"The air here is thickly contaminated. Elders and children arrive at the hospital with wet sheets over their faces; they cannot breathe and we have not enough medicine.

"Not only that, people continue to eat vegetables grown in this area - the few vegetables which survived the fire, the smoke, the sulphur - this means that those who do not get sick now will get sick in the coming months."

| Feature continues below photo |

|

| The plumes of smoke from the oil well fires cover a vast area, poisoning everything in their path [Getty] |

In a report published on November 11, Human Rights Watch speaks of at least seven people with wounds found in at least seven persons consistent with exposure to low levels of a chemical "blister" agent.

"[IS] attacks using toxic chemicals show a brutal disregard for human life and the laws of war," said

Lama Fakih, HRW Deputy Director for the Middle East. "As [IS] fighters flee, they have been repeatedly attacking and endangering the civilians they left behind, increasing concerns for residents of Mosul and other contested areas."

Memories of two years of terror hide behind the eyes of the children here, as they now fill their slow, empty days watching the tall flames not fair from their homes.

Mahmoud worked for the Iraqi army before the 2014 assault by IS. He is about 30 years old. He shakes his head and asks the children: "How long since you went to school?"

"Two years," the children reply.

Mahmoud turns to us. "Two years without school," he says. "This is the most significant damage left by IS. More than the flames - that sooner or later we will extinguish - more than respiratory problems, because we will all have to die sometime.

"The lack of education is the most dangerous damage. Around here they organised training camps. Young boys arrived from Syria and from Turkey.

"They also wanted to drag our children to training camps to teach them to kill. With some they succeeded. Those children are lost, forever."

Makhmoud holds a cigarette in his left hand, he rotates it nervously between two fingers, then he shows it proudly.

"The first time I was surprised while smoking, they made me pay a fine of 300,000 dinars. They told me it was just a warning, and the next time they would cut off my head. The same people who forbade us to smoke cigarettes set fire to our main wealth, oil."

|

The same people who forbade us to smoke cigarettes set fire to our main wealth, oil |  |

Mahmoud remembers public executions, officials hanged on a bridge for three days: a warning to the town's population.

He remembers people flogged in the marketplace; the shops forced to pay taxes to IS and those simply forced to close down.

He remembers all his acquaintances who supported IS "because they thought it would guarantee them a decent life, but a decent life has not ever arrived - and now we risk to lose a generation of children if we don't free them, patiently, from the corrupt information they received in the IS school, about life, about death and about religion".

Now in Qayyara the schools are closed, the houses are covered with grime and residue from the smog.

From a distance, Qayyara looks like the apocalypse itself - like towns in Kuwait during the first Gulf War, like a pirouette of history.

At that time, Saddam Hussein used the same strategy before retreating: set fire to the oil wells to set back the advance of the allied forces.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

More than 700 oil wells were set ablaze in 1991; extinguishing them took more than a year.

Qayyara, a predominantly Sunni city, rich in wells, is now experiencing a similar fate.

And under the sky blackened by oil, its destruction is all the more evident.

The two main oil fields in the region, Qayyara and Najma, produced up to 30,000 barrels of oil per day before IS took over, and, according to experts, IS would likely have continued to extract oil, sending up to 50 tanker trucks a day to Syria.

"As long as they were sure of controlling the city," concludes Mahmoud, "they exploited all our oil."

He continues: "They sold it on the black market. Today we have nothing, no house, no job, nor the wealth of the country: oil."

Teenagers gather around the wreckage of a car, proudly watching a video on a mobile phone. There is the corpse of an IS fighter on the screen.

A man gives a knife to a boy and orders him to behead him.

The body is naked and then tied to a car, dragged through the streets of Qayyara among the jubilant cries of the people. Among the jubilant shouts of children.

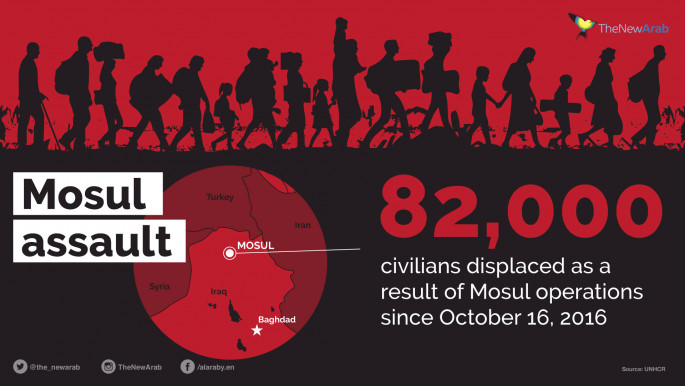

The liberation of Mosul and its surrounding villages poses risks beyond the expected military dangers, as the enemy becomes ever more brutalised, dehumanised.

The same children playing football in front of the flames, trying to regain their denied innocence, the same children who desperately need the purity of their childhood, are being encouraged by the adults of their community to lash out ferociously at the dead bodies of the enemy.

For adults, this liberation means revenge.

The defeat of IS in Mosul is already written, but the group's resistance will be hard, drawn-out and bloody. Meanwhile, the victors - now allies - are sowing the ground with hatred, prolonging the torment of the next generation and preparing the wars of tomorrow.

Francesca Mannocchi is a journalist who has been covering the front lines in the battle for Mosul. Follow her on Twitter: @mannocchia

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News