Egypt's jailed children

Egypt's jailed children

Feature: Despite official denials, eyewitnesses and parents say children are being held in Egyptian prisons with adults, and in atrocious conditions.

5 min read

Children alleged to have taken part in protests have been rounded up in Egypt [AFP]

Early one morning in October 2014, an Egyptian family woke up to violent knocking on their front door.

Panicked and alert, the mother was reminded of the days of Hosni Mubarak, when the police visited their home late one night to arrest her husband.

He was later killed when police fired on demonstrators at Rabaa Square in August 2014.

She was left with her only son, Osama Rida, to take care of the family.

Political prisoners

This time around, the police were here for her 16-year-old son.

"Your son's a terrorist and we are going to arrest him because he is waging war against the state," the police shouted through the closed door, threatening to kick it in.

An officer stormed into the boy's room, where he was sitting with his sisters. Rida was handcuffed and thrown him into the back of an unmarked car.

"He was held in an undisclosed location for two weeks," said his mother. "We looked for him in all the police stations but we only found out where he was when he was brought before a court."

Signs of torture were evident, including marks from electric shocks.

The court announced that Rida would be given a three-year prison sentence.

Recently out of prison, 19-year-old Mohammed - not his real name - was held with Rida in a Nasr city police station.

Sixty-five prisoners were held in a tiny, dark cell with an open toilet, he said.

"Forty five of us would sleep on the ground side-by-side, while the rest would stand waiting for their turn to sleep," said Mohammed.

"We had to pay 20 Egyptian pounds ($2.6) a day to the head warden as protection money, to stop us from being beaten up by the police men and other criminals."

The cell was so crowded, Rida did not have enough space to prostrate when praying, so had to perform his supplications standing.

They both paid the head warden and a police officer 350 pounds ($46) to move into cell number one - a luxury cell holding just 20 people. It was brightly lit, had two fans, two air vents - and a toilet with a curtain.

They were forced to pay the head warden 100 pounds ($13) a day to stay there, said the inmates.

Ibrahim Rida Ahmad was a 17-year-old student at a technical college in the village of al-Shawami, in Dakhliya province. He and his mother travelled to the provincial capital, Mansoura, to visit the city's university and ask about the courses on offer.

Their visit coincided with student demonstrations and Ibrahim was arrested as he stood outside the university's main gate.

He was charged with setting fire to the university's gate, attacking university security and disturbing the peace.

Ibrahim's health records show that as a child he suffered from cerebral atrophy and partial paralysis.

It left him deaf in his left ear, visually impaired and unable to handle loud noises or high temperatures - conditions which would make it difficult for him to carry out the crimes he was alleged to have committed.

These medical documents were presented to court but did not prevent the judge from sentencing him to five years in prison - later reduced to two years.

Minor infractions

Ibrahim's mother, Nabiyat Hakim, said he was tortured at Dikirnis police station:

"My mentally disabled son and the other detainees said they were beaten and electrocuted for no reason. After they moved him to al-Marg juvenile detention centre I found out he was tortured."

Mohammad al-Baqir, a human rights lawyer with the Adala Centre in Egypt, was held in Nasr City police station during the 2014 anniversary of the January 25 revolution.

Held in a cell with the adults were three children, aged 14, 16 and 17.

The 17-year-old was from Kafr El-Sheikh and was a student at al-Azhar University. He was charged with breaking a police officer's arm, stealing an armoured vehicle and using an automatic weapon.

Most of the minors arrested for "political crimes" are held either at Shubra al-Kheima police station or Wadi al-Natrun prison, a central security base in Banha - the state security building in 6th October City.

Baqir said that one boy was being held because police wanted to exchange him for his father - a wanted man.

Courts demanded that the boy should be released, but he is still being held.

Al-Dour al-Rabia detention centre in Alexandria is another popular destination for convicted minors - and is commonly charmingly referred to as "the slaughterhouse".

Human rights groups are trying to document the abuses and torture alleged to be taking place in these detention centres.

Article 112 of the Egyptian child law says children cannot be detained in the same places as adults.

Minors must be separated according to age, gender, and the nature of their crimes.

The law also states that children can be sentenced to jail for no less than three months and not more than two years, which contradicts evidence al-Araby al-Jadeed has seen from witnesses and relatives.

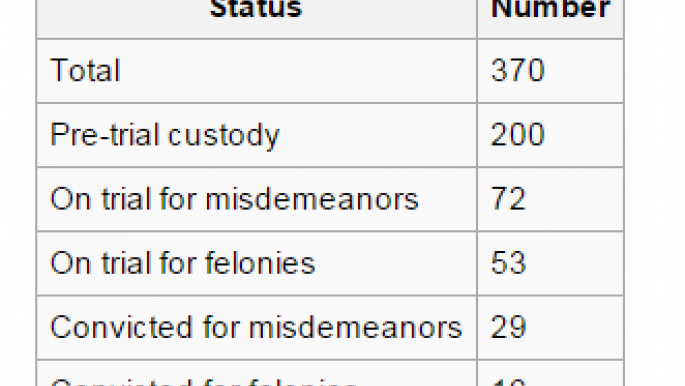

Campaign group Free the Children reported that, between the end of June 2013 and November 2014, 370 people under the age of 18 were detained by Egyptian authorities.

Baqr believes that the Egyptian regime is worried that these children will become the opposition activists of the future.

Radi Abd al-Ati, head of the community outreach and human rights programme at the interior ministry, rejected claims of abuse.

"There are no secret places for detaining children in state security military camps or secret police prisons, and all prisoners are taken care of appropriately," he said.

"The numbers that you have documented are untrue. This organisation [Free the Children] is trying to ruin Egypt's reputation abroad through its lies and accusations.

"All prisoners are subject to the treatment laid out in international human rights conventions and there are continuous inspections of police stations and prisons."

This article is an edited translation from our Arabic edition.

Panicked and alert, the mother was reminded of the days of Hosni Mubarak, when the police visited their home late one night to arrest her husband.

He was later killed when police fired on demonstrators at Rabaa Square in August 2014.

She was left with her only son, Osama Rida, to take care of the family.

Political prisoners

This time around, the police were here for her 16-year-old son.

"Your son's a terrorist and we are going to arrest him because he is waging war against the state," the police shouted through the closed door, threatening to kick it in.

An officer stormed into the boy's room, where he was sitting with his sisters. Rida was handcuffed and thrown him into the back of an unmarked car.

"He was held in an undisclosed location for two weeks," said his mother. "We looked for him in all the police stations but we only found out where he was when he was brought before a court."

|

|

Signs of torture were evident, including marks from electric shocks.

The court announced that Rida would be given a three-year prison sentence.

Recently out of prison, 19-year-old Mohammed - not his real name - was held with Rida in a Nasr city police station.

Sixty-five prisoners were held in a tiny, dark cell with an open toilet, he said.

"Forty five of us would sleep on the ground side-by-side, while the rest would stand waiting for their turn to sleep," said Mohammed.

"We had to pay 20 Egyptian pounds ($2.6) a day to the head warden as protection money, to stop us from being beaten up by the police men and other criminals."

The cell was so crowded, Rida did not have enough space to prostrate when praying, so had to perform his supplications standing.

They both paid the head warden and a police officer 350 pounds ($46) to move into cell number one - a luxury cell holding just 20 people. It was brightly lit, had two fans, two air vents - and a toilet with a curtain.

They were forced to pay the head warden 100 pounds ($13) a day to stay there, said the inmates.

Ibrahim Rida Ahmad was a 17-year-old student at a technical college in the village of al-Shawami, in Dakhliya province. He and his mother travelled to the provincial capital, Mansoura, to visit the city's university and ask about the courses on offer.

Their visit coincided with student demonstrations and Ibrahim was arrested as he stood outside the university's main gate.

|

|

He was charged with setting fire to the university's gate, attacking university security and disturbing the peace.

Ibrahim's health records show that as a child he suffered from cerebral atrophy and partial paralysis.

It left him deaf in his left ear, visually impaired and unable to handle loud noises or high temperatures - conditions which would make it difficult for him to carry out the crimes he was alleged to have committed.

These medical documents were presented to court but did not prevent the judge from sentencing him to five years in prison - later reduced to two years.

Minor infractions

Ibrahim's mother, Nabiyat Hakim, said he was tortured at Dikirnis police station:

"My mentally disabled son and the other detainees said they were beaten and electrocuted for no reason. After they moved him to al-Marg juvenile detention centre I found out he was tortured."

Mohammad al-Baqir, a human rights lawyer with the Adala Centre in Egypt, was held in Nasr City police station during the 2014 anniversary of the January 25 revolution.

Held in a cell with the adults were three children, aged 14, 16 and 17.

The 17-year-old was from Kafr El-Sheikh and was a student at al-Azhar University. He was charged with breaking a police officer's arm, stealing an armoured vehicle and using an automatic weapon.

Most of the minors arrested for "political crimes" are held either at Shubra al-Kheima police station or Wadi al-Natrun prison, a central security base in Banha - the state security building in 6th October City.

Baqir said that one boy was being held because police wanted to exchange him for his father - a wanted man.

Courts demanded that the boy should be released, but he is still being held.

|

|

Al-Dour al-Rabia detention centre in Alexandria is another popular destination for convicted minors - and is commonly charmingly referred to as "the slaughterhouse".

Human rights groups are trying to document the abuses and torture alleged to be taking place in these detention centres.

Article 112 of the Egyptian child law says children cannot be detained in the same places as adults.

Minors must be separated according to age, gender, and the nature of their crimes.

The law also states that children can be sentenced to jail for no less than three months and not more than two years, which contradicts evidence al-Araby al-Jadeed has seen from witnesses and relatives.

Campaign group Free the Children reported that, between the end of June 2013 and November 2014, 370 people under the age of 18 were detained by Egyptian authorities.

Baqr believes that the Egyptian regime is worried that these children will become the opposition activists of the future.

Radi Abd al-Ati, head of the community outreach and human rights programme at the interior ministry, rejected claims of abuse.

"There are no secret places for detaining children in state security military camps or secret police prisons, and all prisoners are taken care of appropriately," he said.

"The numbers that you have documented are untrue. This organisation [Free the Children] is trying to ruin Egypt's reputation abroad through its lies and accusations.

"All prisoners are subject to the treatment laid out in international human rights conventions and there are continuous inspections of police stations and prisons."

This article is an edited translation from our Arabic edition.

![Palestinians mourned the victims of an Israeli strike on Deir al-Balah [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2024-11/GettyImages-2182362043.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=xSHZFbmc)

![The law could be enforced against teachers without prior notice [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2178740715.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=hnqrCS4x)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News