Syrian refugees stuck between war and inefficient aid

A group of children run towards the person holding a camera. Jumping enthusiastically up and down, they ask for “Sura, sura, moallem, sura” (Photo, photo, mister, photo). With their shinning eyes, looking at their own photographs on the camera's small LCD screen, they resume their excited shouting: "Sura, sura, sura."

Isolated and bored Syrian refugee kids, get exultant with a modest cheer. But it is not easy to see a slight sign of happiness on their parents' faces: parents who have been struggling through the cold winter, heavy snows, and poor living conditions in makeshift huts in informal settlements in the Lebanon's Bekaa Valley.

Over 1.17 million registered Syrian refugees are in Lebanon, which now ranks first in the world in refugees per capita, according to a report published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on March 8.

It is claimed that the actual number of Syrian refugees in Lebanon is much higher than those officially registered. Official Lebanese estimates put the number at about 1.7 million.

One of the main challenges of delivering aid to Syrian refugees is funding. Assistance to Syrian refugees still falls short of their needs. UNHCR data from 9 March revealed that only eight per cent of the money needed for Syrian refugees humanitarian assistance in 2015, has been funded so far.

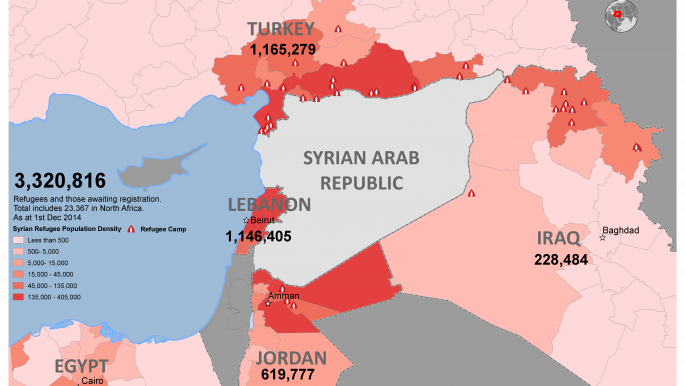

|

| A total of 3.8 million Syrians have fled to neighbouring countries [UNHCR] |

Although financial backing is the main issue facing the current refugee crisis across Syria and neighbouring countries, more concealed problems exist on the ground. A numbers of aid workers in Lebanon believe that the main international aid organisations have wasted money and available resources due to cumbersome bureaucracy, a lack of coordination and the duplication of services.

Firas, a young Syrian who works for a local NGO in Lebanon, argued that a large percentage of international organisations’ funds are allocated to "non-operational activities". In his opinion time-consuming assessments and too much bureaucracy prevents international organisations having a timely humanitarian response.

"All the big international NGOs carry-out individual assessments that are often repeated in the same area, among the same group and are about the same needs," Firas told Al-Araby al-Jadeed.

He said until international aid agencies begin coordinating their activities, they will "either deliver assistance to the same place twice or assess humanitarian needs twice."

International organisations have their own rules and regulations. Aid workers working for the International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC) do not agree with Firas. They emphasise that long-term assessment is the cornerstone of aid delivery in regions that descend in humanitarian crisis.

ICRC Head of Communication in Lebanon Soaade Messoudi, who has also worked in Libya, the Philippines and Darfur, stressed: "We don't drop aid on people, we organise, we carry out serious assessments, and deliver aid to people in a dignified way."

The ICRC, besides providing healthcare and treatment for Syrian refugees in Lebanon wounded in the fighting, has distributed relief goods, cash assistance and food parcels among refugees in Bekaa valley during the winter.

In November, under its winterization plan, the ICRC signed an agreement to coordinate with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). It was the first agreement of its kind since the beginning of the civil war in Syria, and it covered 11,100 refugees, who have sought shelter in the Bekaa valley.

However, all the Syrian refugees in Lebanon are not as lucky as those 11,100. Many on the outskirts of the northern city of Ersal were totally disconnected from local and international relief providers after the January heavy storm in the region.

|

| There's been a steady increase in the massses of refugees leaving Syria [UNHCR] |

A member of staff for an international aid organisation operating in Ersal since 2012, who asked not to be named as he was not authorised to speak on the issue, told al-Araby al-Jadeed: "This is the fourth winter that refugees have lived in makeshift settlements in Lebanon. But aid organisations have not prepared an effective response plans. When refugee kids die frozen, then aid providers plan for emergency help."

In January and February he captured videos of Jarrod Ersal area near the Lebanese-Syrian borderline that show refugees makeshift huts were totally covered with heavy snow and aid workers' vehicles could hardly reach the settlements. He said that, "No one dares to go there, because these camps are located after the army's last checkpoint and IS militants control the area," using an acronym for the Islamic State group (formerly known as Isis).

A total of 3.8 million Syrian refugees have fled to neighbouring countries and North Africa since 2011. According to the UN data, 36 percent of those who sought refuge in Lebanon are within the "severely and moderately economically vulnerable categories".

Let's interpret the previous sentence in a more understandable way. It means at least 407,000 Syrian refugees in Lebanon are too poor to have sufficient food to eat, warm their makeshift huts in the winter or provide medicine for their sick children or elderly family members.

The refugees' vulnerability increases as the funding crisis of international and local organisations worsened. In February, the World Food Organization (WFO) reduced the number of assisted Syrian refugees in Turkey from 220,000 to 154,000 due to a shortage of funding.

Possibly even coordination of all local and international organizations and NGOs would not cover the Syrian refugees' needs. But it could be a unique way to deliver efficient assistance to people escaping their war-torn country and leaving behind all their belongings.

"The problem in this part of the world is to make people understand we are not here to respond to every need. We cannot. We don't have the budget for it," said Messoudi.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News