Lebanon's impoverished Tripoli a launching pad for Europe-bound migrants

Feature: A ferry line between Tripoli and Turkey has become part of the route to Europe used by Syrian and Palestinian refugees, as well as Lebanese youths and families.

4 min read

Migrants and refugees are now travelling to Turkey by ferry from Tripoli, northern Lebanon [Getty]

In the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli, it is as if one problem ends only for another to begin.

Nearly 17 months ago, the Lebanese government deployed the army in a security plan designed to end recurrent rounds of sectarian fighting between the slums of Jabal Mohsen and Bab al-Tabbaneh.

Rival politicians in the city and beyond were accused of arming local militants, fuelling those clashes.

However, the end of the violence was not the end of Tripoli's many woes, and today, immigration to Europe from Tripoli via Turkey is fast becoming a major issue.

A poor city

Tripoli suffers from chronic underdevelopment and neglect by the central government in Beirut. This has left the city with some of the highest unemployment and poverty rates in the country.

In truth, this is one reason why dozens of youths from north Lebanon and Tripoli have joined the likes of the Islamic State group and the Nusra Front in Syria. Several have gone on to carry out suicide attacks.

A study by UN-ESCWA in January concluded that Tripoli was in general an impoverished city, with some pockets of luxury while 57 per cent were deprived, and of these, 26 percent "extremely deprived".

Promises of political leaders regarding development plans to mitigate poverty are yet to be delivered, in a country continuously plagued by crises.

Ferry to Europe

It was therefore no surprise that a ferry line between Tripoli and the Turkish shore, launched three years ago, became part of the migration route for refugees and asylum-seekers bound for Europe. In recent months, the ferry line carried nearly 30,000 passengers each month.

An official at the port of Tripoli, who asked not to be named, told al-Araby al-Jadeed's Arabic service that this year, more than 90,000 passengers - 90 percent of whom are Syrian nationals - have used the ferry service. The official said that only five percent have returned.

But although the majority are Syrians or Palestinians, many of whom fed up with their conditions in Lebanon, there are still a significant number of Lebanese using the route to emigrate to Europe.

And it's not just youngsters, but entire Lebanese families.

There are hundreds of Lebanese nationals, some say as many as 1,700, who have emigrated from Tripoli and surrounding areas using the ferry service.

Another route from Lebanon is the international airport in Beirut, with up to ten flights a day flying to Turkey. The ferry ticket costs $150, an airfare sells at around $300.

It is not poor Tripolitans and Lebanese alone who are taking the journey. Some are students who believe they have no prospects in the country. Some are even salaried employees, according to sources in the city, fed up with the political situation in the country.

Another segment of Tripolitans fleeing to Turkey are hundreds of disillusioned jihadists who had been fighting in Syria.

According to Islamist sources, many of them are unwilling to return full-time to Lebanon, where they could be prosecuted, and thus make their way to Europe among other refugees and migrants.

Frozen solutions

There have been many ideas on how to tackle the underlying problems behind both rising emigration and extremism.

These include development plans for the city and the rest of north Lebanon; plans to tackle religious radicalisation in cooperation with Dar al-Fatwa, the supreme Sunni religious authorities; and a political and legal plan to deal with the harsh sentences given to Sunni Islamist youths, compared with the leniency shown to Hizballah youths fighting in Syria.

Yet it is hard to expect the authorities to implement any of these plans, at least in the near future, given the total collapse of political institutions and public services in the country.

The situation in Tripoli is so dismal that a political official in the city told al-Araby al-Jadeed the biggest mistake Tripoli and the North Governorate made was to join the State of Greater Lebanon carved out of Syria by the French in 1920.

Since then, Tripoli has been cut off from what some believe to be its natural extension in the Syrian hinterland and Iraq beyond it, and has quickly been eclipsed by Beirut, despite being called Lebanon's second capital.

Mistrustful of the central government, some Tripolitans even still dream of secession from Lebanon.

This is an edited translation from our Arabic edition.

Nearly 17 months ago, the Lebanese government deployed the army in a security plan designed to end recurrent rounds of sectarian fighting between the slums of Jabal Mohsen and Bab al-Tabbaneh.

Rival politicians in the city and beyond were accused of arming local militants, fuelling those clashes.

However, the end of the violence was not the end of Tripoli's many woes, and today, immigration to Europe from Tripoli via Turkey is fast becoming a major issue.

A poor city

Tripoli suffers from chronic underdevelopment and neglect by the central government in Beirut. This has left the city with some of the highest unemployment and poverty rates in the country.

In truth, this is one reason why dozens of youths from north Lebanon and Tripoli have joined the likes of the Islamic State group and the Nusra Front in Syria. Several have gone on to carry out suicide attacks.

A study by UN-ESCWA in January concluded that Tripoli was in general an impoverished city, with some pockets of luxury while 57 per cent were deprived, and of these, 26 percent "extremely deprived".

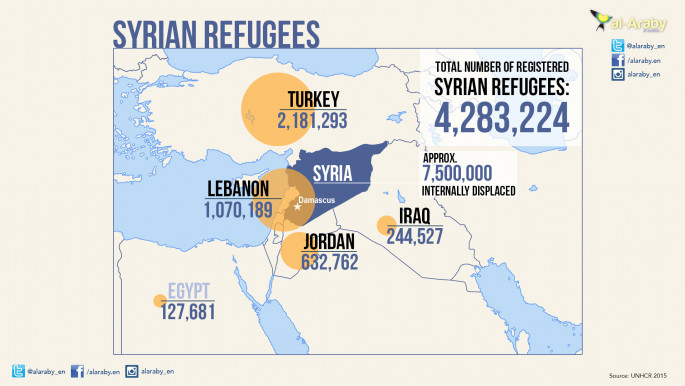

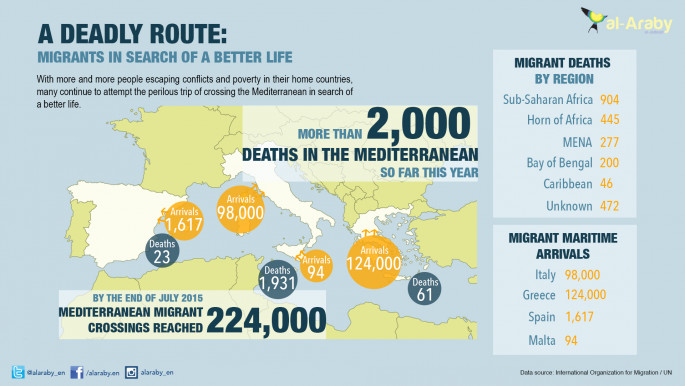

|

|

| Click to enlarge |

Promises of political leaders regarding development plans to mitigate poverty are yet to be delivered, in a country continuously plagued by crises.

Ferry to Europe

It was therefore no surprise that a ferry line between Tripoli and the Turkish shore, launched three years ago, became part of the migration route for refugees and asylum-seekers bound for Europe. In recent months, the ferry line carried nearly 30,000 passengers each month.

An official at the port of Tripoli, who asked not to be named, told al-Araby al-Jadeed's Arabic service that this year, more than 90,000 passengers - 90 percent of whom are Syrian nationals - have used the ferry service. The official said that only five percent have returned.

But although the majority are Syrians or Palestinians, many of whom fed up with their conditions in Lebanon, there are still a significant number of Lebanese using the route to emigrate to Europe.

And it's not just youngsters, but entire Lebanese families.

There are hundreds of Lebanese nationals, some say as many as 1,700, who have emigrated from Tripoli and surrounding areas using the ferry service.

Another route from Lebanon is the international airport in Beirut, with up to ten flights a day flying to Turkey. The ferry ticket costs $150, an airfare sells at around $300.

It is not poor Tripolitans and Lebanese alone who are taking the journey. Some are students who believe they have no prospects in the country. Some are even salaried employees, according to sources in the city, fed up with the political situation in the country.

Another segment of Tripolitans fleeing to Turkey are hundreds of disillusioned jihadists who had been fighting in Syria.

According to Islamist sources, many of them are unwilling to return full-time to Lebanon, where they could be prosecuted, and thus make their way to Europe among other refugees and migrants.

Frozen solutions

There have been many ideas on how to tackle the underlying problems behind both rising emigration and extremism.

These include development plans for the city and the rest of north Lebanon; plans to tackle religious radicalisation in cooperation with Dar al-Fatwa, the supreme Sunni religious authorities; and a political and legal plan to deal with the harsh sentences given to Sunni Islamist youths, compared with the leniency shown to Hizballah youths fighting in Syria.

Yet it is hard to expect the authorities to implement any of these plans, at least in the near future, given the total collapse of political institutions and public services in the country.

The situation in Tripoli is so dismal that a political official in the city told al-Araby al-Jadeed the biggest mistake Tripoli and the North Governorate made was to join the State of Greater Lebanon carved out of Syria by the French in 1920.

Since then, Tripoli has been cut off from what some believe to be its natural extension in the Syrian hinterland and Iraq beyond it, and has quickly been eclipsed by Beirut, despite being called Lebanon's second capital.

Mistrustful of the central government, some Tripolitans even still dream of secession from Lebanon.

|

This is an edited translation from our Arabic edition.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News