Protecting Middle East heritage from Islamic State

The Islamic State [IS] group has been on a systematic campaign to destroy historic sites across the territory it controls in Iraq and Syria, ruthlessly destroying and looting artefacts that fall into its hands.

The group's advances mean antiquities in Syria and Iraq face the danger not just of damage but of intentional eradication.

The most recent example was the destruction of the famed temples in the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra. Satellite images showed that the two temples, which had survived for nearly 2,000 years, reduced to rubble.

| We have a story to tell there that we can't lose for our children and grandchildren... Our heritage is much more than our collective memory. It is our collective treasure - Ben Kacyra |

Earlier this month, the militants destroyed The Arch of Triumph, one of the most recognisable sites in Palmyra, the central city affectionately known by Syrians as the "Bride of the Desert".

Historical sites have been damaged constantly since the war in Syria began, struck by shelling and government airstrikes or exposed to rampant looting. Syrian government officials say they have moved some 300,000 artefacts from around the country to safe places over recent years, including from IS-controlled areas.

The rush has been on to find creative, and often high-tech ways, to protect Syria's millennia-long cultural heritage in the face of the threat that much of it could be erased by the country's war, now in its fifth year.

One of these include the Million Image Database project – a US-funded project which seeks to provide local conservators with resources to help safeguard relics.

Backed by UNESCO, it aims to "flood the region" with low-cost, easy-to-use 3-D cameras, delivered to activists to document antiquities in their area.

"I don't want to be having this conversation with somebody three years down the road, and they say, 'why didn't you start in 2015 when they [IS] only controlled three percent of the sites'," said Roger Michel, behind the Million Image Database, an Oxford Institute of Digital Archaeology project.

The point-and-shoot cameras, which cost about $50 each, take a stereoscopic image of the relics, with a granularity of detail measured in centimetres. The aim is to distribute 5,000 cameras region-wide by next year, at a total coast of $3 to $6 million.

"The idea is to have as many images made of as many objects and buildings as possible in advance of the destruction by the IS forces," Michel said.

|

|

| Palmyra sculptures [Getty] |

Nearly 1,000 cameras have already been deployed or are on their way, not only to Syria, but also Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, Turkey, Jordan and Egypt.

The camera user can then upload the pictures or videos to the project's website. The website is closed to the public to protect the activists' anonymity and to ensure the site remains a purely scholarly venture, not a social media platform for activists, said Alexy Karenowska, a physicist who developed the web interface and is the project's technology director.

As the project progresses, it will find a way to share storytelling from the material to the public, she said.

The project has also linked up with a leading Chinese 3-D concrete printing company to consider eventually reconstructing some of the architecture that has been destroyed.

A separate project would carry out far more detailed scans of antiquities in Syria and Iraq using laser scanners. The scanners bounce lasers off the surface of objects in the field, measuring millions of points a second to create a data set known as a point cloud.

The data can be used to create 3-D images accurate to two or three millimetres to create models or virtual tours of the sites or allow full-scale reconstructions.

But while the scanning brings the highest precision, it also requires experts, accompanied by security teams, to visit the sites to scan them over extended periods of time using precise equipment – a much more unwieldy footprint in potentially dangerous areas than the 3-D cameras.

The project, called Anqa, the Arabic word for the phoenix, the legendary bird that rises from the ashes, aims to laser-scan 200 objects in Syria, Iraq and other parts of the region.

It will work with the government antiquities departments in Syria and Iraq, as well as UNESCO, to deploy teams in northern and southern Iraq, Damascus and other areas, its director Ben Kacyra, of the California-based scanning non-profit CyArk, said. For security considerations, he would not specify what sites he plans to scan.

"We have a story to tell there that we can't lose for our children and grandchildren," Kacyra said. "Our heritage is much more than our collective memory. It is our collective treasure."

Kacyra, an engineer originally from the Iraqi city of Mosul, and his wife set up CyArk to digitally preserve heritage sites around the world after the 2001 destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan.

One site he scanned, the Kasubi royal tombs in Uganda, were torched in 2010, and now the government is using his imagery to reconstruct them. After Mosul fell to Islamic State group control in 2014 and the extremists began destroying antiquities there, Kacyra focused on documenting heritage in the Mideast.

|

|

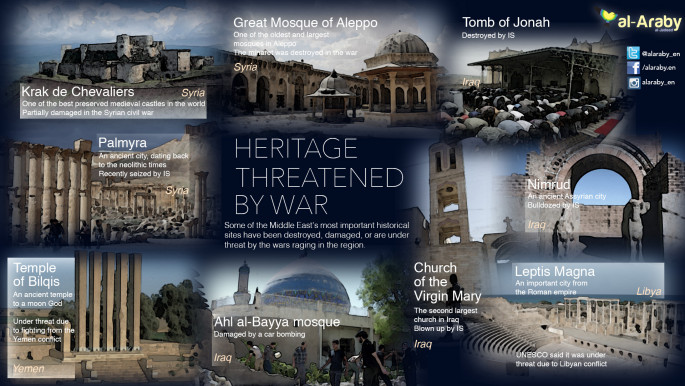

| Mid East heritage threatened by war: Click to enlarge |

Another campaign is taking a more low-tech approach aiming at directly protecting at least some sites.

The project, by the American Schools of Oriental Research, provides supplies and funding to local experts and volunteers for things like crates to store artefacts or sandbags to pack around unmovable structures to give some protection against shelling or bombs, said LeeAnn Gordon, project manager for Conservation and Heritage Preservation at ASOR, which receives US State Department funding.

"What we are really looking for is these kinds of small projects that can have big impact," Gordon said. "Syria has so much. In my opinion, there is still more intact than there is destroyed."

But, hemmed in by the US policy toward Syria, the initiative can't fund government efforts or governmental groups, leaving it fewer options in a country divided between government-controlled, rebel-held and IS-held areas.

ASOR is also using satellite images to track destruction of antiquities.

In one those rebel-held territories, little technology or resources are available to Suleiman al-Eissa, a history teacher who is now leading a self-created "revolutionary" antiquities department to protect the Roman-era ruins in his hometown of Busra Sham, one of the six UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Busra Sham, in the southern Daraa province, fell to the rebels from the Free Syrian Army in March, who formed a battalion to protect the city's ancient site from looting and further damage.

Al-Eissa is currently documenting what has been damaged in the city and what remains, to account for the looting that took place when the town was government-controlled.

"There is no IS or al-Qaida here," he said through a Whatsapp call. "But Busra Sham is one of the only ancient cities still left in Syria. We are trying to protect it."

With additional reporting Sarah el Deeb, Associated Press

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News