Shapeshifting Sadr will not bring change to Iraq

In what some see as a major upset in the Iraqi political scene, Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr appears to have won the most seats following last week's elections, placing his Sairoun bloc in an advantageous position.

This has led some commentators to speculate that Sadr's election victory could begin to dent Iranian influence, and soothe the crippling and divisive sectarianism that has gripped Iraq since the Saddam Hussein dictatorship was toppled in 2003. However, such analysis underplays the effect that disenfranchisement had on the result, and is dangerously amnesiac when it comes to Sadr's own violent, sectarian past.

Sadr's shapeshifting loyalties

In recent years, Sadr has positioned himself as the voice of anti-sectarianism, anti-Iranian interference and anti-corruption in a political environment known to be rife with all three, and that Iraqis have grown to loathe.

Sadr - mockingly nicknamed "Sayyed Atari" for his alleged love of video games over religious study - capitalised on negativity toward the political class, and ran on an anti-sectarian and anti-graft ticket alongside the Iraqi Communist Party, calling for Iraqis to take charge of their own destiny, rather than cede it to foreign interlopers such as Iran.

But Sadr conveniently fails to mention that he has been one of the biggest beneficiaries of Iranian patronage, and even before the illegal US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Read more: Sadr's Iraq: A vote against sectarianism and corruption

Tehran hosted a young Muqtada - whose ancestry is Lebanese and Iranian - and the scion of the famous Sadr family of Shia clerics spent many years living in Iran. This relationship with the mullah regime allowed Sadr to be one of the first of Iran's proteges in setting up a militia following the collapse of Saddam's Baathist regime, the infamous Mahdi Army.

Under Sadr's spiritual leadership, the Mahdi Army began a campaign of violence against not only occupying American and British soldiers, but also against Iraqis themselves.

|

Sadr has been a net beneficiary of Iranian aid, assistance and support |  |

Having been trained by another Iranian proxy, the Lebanese Hizballah, Sadr's men began infiltrating local police forces in Iraq and targeting people for assassination, including former Baath Party officials, Sunni "undesirables", and operating racketeering rings. Not even western journalists were safe, the kidnap and murder of the New York Times' Steven Vincent after he reported on the Mahdi Army's activities a stark example.

The Mahdi Army operated death squads targeting Iraqi Sunnis and perpetrating some of the worst examples of sectarian cleansing in the modern Middle East. According to a 2006 Channel 4 documentary on the phenomenon of sectarian violence, Shia death squads - of which Sadr's Mahdi Army was a major contributor - may have led to the deaths of 655,000 in just three years since the US invasion. While Sadr was not the only sectarian warlord to run a death squad, there can be no doubt that his vicious reign was directly supported by Iran.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

Far from being anti-Iran, Sadr has been a net beneficiary of Iranian aid, assistance and support. It would be naive to think that a few tantrums thrown by Sadr against Iran over the years would destroy the kind of bond forged by Tehran providing refuge, arms, money, men, and even educating the wayward Sadr.

Iran has already stated that it will "not allow liberals and communists to govern in Iraq", so it remains to be seen what kind of pressure Tehran will bring to bear on its protege.

Iraqis' loss of faith in democracy helped Sadr win

While Sadr did not run as a candidate himself, he can still have a potentially decisive voice when selecting who will succeed outgoing prime minister Haider al-Abadi, whose Victory Alliance was shunted unceremoniously into third place. Indeed, if Sadr's Sairoun coalition cuts a deal with Abadi to remain in office with a Sadrist-dominated cabinet, the premier may find himself in Sadr's debt.

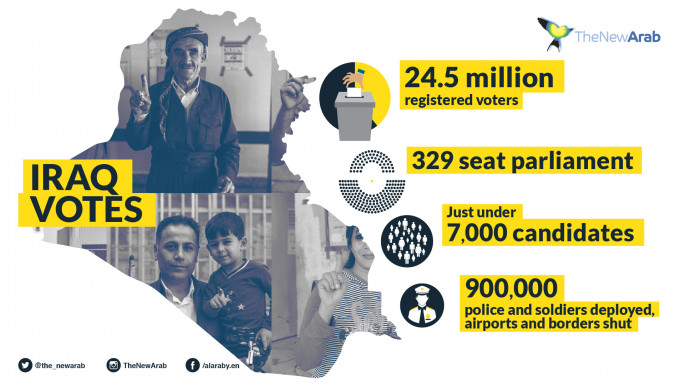

It's also important to note that Sadr's position of influence is not down to any particular influence he wields over a large cross-section of Iraq's multi-ethnic, multi-sect society. After all, his bloc achieved 54 out of 329 seats, hardly suggesting that he is a champion of the people. In reality, a number of factors contributed to his victory:

|

Had Iraq had a functioning democracy, however, Sadr's fortunes may not have been so lucky |  |

First, the voter turnout reached historically low figures of just 44 percent, perhaps indicative of Iraqi fatigue with the seemingly unchanging nature of their political system which has allowed Iraq to become one of the most corrupt countries on the planet. A grassroots campaign has also resonated with Iraqis, calling on them to boycott the elections as the same faces who have already been accused of corruption were again running for office.

Twitter Post

|

Second, and a major contributing factor to the all-time low turnout, is the fact that millions of Iraqis are still languishing in internally displaced persons camps or are in need of urgent humanitarian assistance. According to UN figures, the number of IDPs is anything between two to three million, while the number those in urgent need of aid is almost as high as nine million.

While some of these will not be eligible to vote because they are minors, others were not even considered as worthwhile targets for political campaigning, with one ally of Abadi describing them as "Daesh families", using an Arabic language acronym for the Islamic State militant group.

Such divisive rhetoric would have undoubtedly fed into the boycott campaign, with many Iraqis sick and tired of the sectarianism afflicting their day-to-day lives.

With so many people not exercising their democratic right to vote - either voluntarily or involuntarily - it is no wonder that more organised political actors such as Sadr were able to mobilise a better turnout and clinch victory.

Had Iraq had a functioning democracy, however, Sadr's fortunes may not have been so lucky.

Follow him on Twitter: @thewarjournal

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News