A return to authoritarianism in Tunisia: A revolution resurfaces (Part II)

Cooperation between the two formations allowed Tunisia to set up the foundations of a consensual legitimacy. But the agreement between the two men quickly turned to a bipolarisation of political life, discrediting other political parties and putting an end to the vitality and pluralism that appeared in the aftermath of the revolution.

Tunisians had to question the consensus: What exactly did the two men agree to do with their shared project? The question was a legitimate one.

During the elections of 2014, besides the questions of security and economic stimulus, two distinct visions for society had emerged through the new polarisation.

Furthermore, when Ennahdha withdrew from the government, an imbalance was created which allowed Rached Ghannouchi, who had remained on the sidelines of his own party, to position himself as the arbiter and wise man of Tunisian political life.

At the apex of the crisis in the summer of 2013, when Ennahdha was accused of mismanagement, clientelism and salafist affinities, he was able to turn the situation around and emerge as a winner.

When his party was rejected by part of the population and forced to leave the government, its leader was able to claim he had withdrawn from the government - not from politics altogether - in the name of general interest and in the service of democracy.

He then announced that Ennahdha would not have any candidate running for the presidential elections and praised the qualities of a national union government which he said represented the country accurately.

|

Essebsi was never a believer in the gains of the revolution, which he regards as a moment of disorder that might have thrown the country into chaos |  |

The vacuum thus created allowed Essebsi to enter the scene even without a real project or political vision. He simply aimed to gather those around him who defended Bourguiba's modernist legacy, which he believed had been threatened by Ennahdha.

All these manoeuvres failed to conceal a pact made between Essebsi, an old man anxious to sit in the Carthage Palace while there was still time, and Rached Ghannouchi, who never stopped claiming time was working in the Islamists' favour.

Other parties and lists which defined themselves as democratic and progressive did not manage to capture Tunisians' attention, and they failed to really stand as viable alternatives.

These were the biggest losers of the electoral consultation. Only the Popular Front which brought together a dozen left-wing formations, nationalists and independent personalities tried to break the polarity.

A possible to return to the old regime

This game of political positioning failed to give the successive ruling classes the means to fight against social inequality, or decrease unemployment which has been on the rise since 2011.

However, what seems to doom the system to lethargy is not so much numbers and figures, but the uncertain economic environment.

|

|

| Civil society, which was on its guard in 2013, might yet be reemerging to remind the politicians of everything they have failed to achieve since 2011 [Getty] |

Nidaa Tounes allowed the old business and influence networks to come back and spread across the administrations like the plague, posing a real threat to the fight against corruption.

The law of "administrative reconciliation" of 17 September 2017 goes even further, giving protection to the political figures of the old regime and suspending all legal actions against them. Essebsi pushed for the law to be adopted.

In reality, Essebsi was never a believer in the gains of the revolution, which he regards as a moment of disorder that might have thrown the country into chaos.

His desire to look to the past is in line with his initial project. Emulating the political practices of the old regime, he aims to fully control executive power.

|

What seems to doom the system to lethargy is not so much numbers and figures, but the uncertain economic environment |  |

The semi-parliamentary regime put in place in 2014 that places most of the executive power in the hands of the prime minster, does not sit well with him.

He chose Youssef Chaed to replace Habib Essid at the head of the government in the summer of 2016 without realising that this young man was going to use his own individual initiative to fight against corruption.

Popular opinion strongly supports this anti-corruption initiative but it risks unsettling both Essebsi and Ghannouchi, who are afraid the results of the investigations could tarnish them and those close to them.

It took Essebssi some cunning to achieve his plans, imposing many ministers from the old regime and officials from the Democratic Constitutional Rally (DRC) inside the government.

Twitter Post

|

He also returned to Habib Bourguiba's policies: Modernist in regard to social welfare, but against all and any political opening or democracy.

On 13 August 2017, to celebrate Women's Day, he cancelled a decree dating from 1973, which forbid marriages between a Tunisian Muslim woman and a non-Muslim man. He also hoped to draw in even closer, the modernist swath of opinion which had overwhelmingly voted for him in 2014, but had subsequently been disappointed by his policies.

Three weeks later on 7 September 2017, he railed against the parliamentary regime in an interview, blaming it for the government's inefficiency.

After placing his own son at the head of Nidaa Tounes, he plans to bring back Ben Ali's political staff in order to rebuild a strong presidential regime. No counter-power is truly opposing his thwarting of the fight against corruption, his stalling of transitional justice or his postponing of municipal elections.

Essebsi's governance oddly recalls those of previous presidents of the republic. But he acts in an environment that has completely changed.

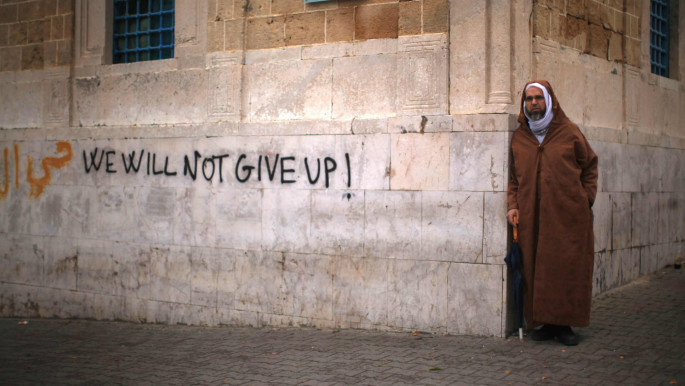

The civil society which was on its guard in 2013 might yet be reemerging from its torpor, to remind the politicians of everything they have failed to achieve since 2011.

The call for a break with the political past might come into fashion again. And the recent protests are a warning shot in his direction.

This is part two, to read part one of the article, click here.

Khadija Mohsen-Finan holds a doctorate in political science (Sciences-Po, Paris) and is a history graduate, teacher and researcher in international relations at the University of Paris I (Pantheon Sorbonne).

This is an edited translation of an article from our partners at Orient XXI.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News