Divisive federalism in Syria: One outcome of Geneva's failure

Comment: The declaration of a federal state in northern Syria seeks to present federalism as a viable solution, when it seems it will only extend the war, argues Karim Barakat.

5 min read

Russian Deputy Foreign Minister suggested that federalism in Syria could be an option [Getty]

The declaration of self-administration by Kurdish groups in northern Syria as an outcome of a conference held in Rmeilan has provoked widespread condemnation from almost all sides in the Syrian conflict.

The opposition's High Negotiations Committee (HNC) was quick to reject the division of Syria into several regions, emphasising the need to maintain a unified state that included the Kurdish constituency.

This position was also adopted by the US, which attempted to ameliorate Turkish concerns of an autonomous Kurdish region in northern Syria by asserting that it opposed such a move.

Moreover, the Assad regime has also refused to endorse dividing Syrian territory into a federal state. Interestingly, however, the Russian side is yet to comment on this latest development. But whereas the prospect of sustaining a Kurdish enclave remains very slim, the announcement itself comes at a critical moment, questioning the possibility of a unified Syria.

Geneva's talks and Russia's withdrawal

The decision of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) to unite three major Kurdish regions in the north of Syria emerged while the Geneva peace talks were being held, having gained new impetus following the cessation of hostilities that has held - to some degree - over the past few weeks.

In addition, Moscow's decision to withdraw most of its forces from Syrian territory has also been regarded positively by the opposition.

The PYD's decision comes at a time when the Turkish government has escalated its attacks on PKK-affiliated groups in both Syria and Iraq following the multiple attacks in Ankara and Istanbul.

The Kurdish move is a timely response to the escalation in Erdogan's anti-PKK campaign on the one hand, and their exclusion from the Geneva peace talks on the other.

Both Assad and Erdogan have warned against the Kurdish manoeuvre under the pretext of retaining the unity of Syria. But while Erdogan has maintained US support, with the United States' refusal to endorse any decision for the formation of a federal system outside the Geneva peace talks, Moscow's position remains ambiguous.

Not long ago, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov had suggested that a federal solution to the Syrian civil war could be an option. The federal solution has also not been rejected by US Secretary of State John Kerry or the Assad regime.

But whereas they have set as a precondition agreement between the different Syrian factions in case the attempts at maintaining a unified Syria do not lead to fruition, Russia remains silent on the viability of the Kurdish proclamation.

Federalism and disunity

The harmful stalemate in the Syrian civil war has motivated international players to push for a settlement. While Russia does not appear to be enthusiastic over establishing an autonomous Kurdish region, Moscow's silence raises questions as to how amenable it really is to the developments instigated by the PYD.

In addition to Putin's obvious goal of spiting Turkey, Russia seems to be waiting for any developments that could follow from the Geneva negotiations.

The Geneva talks, however, appear to be barren so far, with little progress made on the key divisive issues. But while the negotiating sides continue their dispute over basic disagreements, the Syrian Kurds seek to take advantage of the deadlock in order to push for a federal alternative, and present it as a viable solution.

But the declaration of a Kurdish self-governing region has also been opposed by significant Kurdish parties. The Massoud Barzani-supported Kurdish National Council, which is taking part in the peace talks, has rejected such a decision in the absence of agreement with other Kurdish and Syrian factions.

Comparing the Syrian case with the development of an autonomous Kurdish region in Iraq is of significance.

In the Iraqi case, the move towards self-governance was initially the product of a bilateral agreement following a lengthy war between Kurdish militants and the old regime. On the other hand, such an agreement did not happen - and could not have happened - in Syria, in the absence of a legitimate side with which such a covenant could be established.

Given the widespread condemnation of the declaration of a Kurdish self-governed region, the successful implementation of such a solution remains extremely improbable.

Nevertheless, the Kurdish declaration also aims at thwarting any progress made in Geneva. The exclusion of the influential PYD from the peace talks has given the movement the opportunity to act independently of the other Syrian participants. In fact, for a while now, the Kurdish forces have been highly organised in terms of self-governance. This has been reflected in the political and military levels at which the People's Protection Units (YPG) has received support in the US.

What the Kurdish announcement accomplishes, therefore, is bringing to the forefront as a live option the idea of federalism if, as expected, the Geneva talks do not lead to results.

Whereas this could offer one way out of the current stalemate, it is doubtful such measures would or could lead to the reconciliation needed to move beyond the civil war.

While the Rmeilan conference reportedly included non-Kurdish populations, several insurgent groups have declared their intention to pursue armed resistance to prevent the realisation of their federal aspirations. The declaration of self-administration and the responses it has elicited can only serve to extend the crisis at hand rather than offering satisfactory means for political inclusion and transitioning from the state of war.

The opposition's High Negotiations Committee (HNC) was quick to reject the division of Syria into several regions, emphasising the need to maintain a unified state that included the Kurdish constituency.

This position was also adopted by the US, which attempted to ameliorate Turkish concerns of an autonomous Kurdish region in northern Syria by asserting that it opposed such a move.

Moreover, the Assad regime has also refused to endorse dividing Syrian territory into a federal state. Interestingly, however, the Russian side is yet to comment on this latest development. But whereas the prospect of sustaining a Kurdish enclave remains very slim, the announcement itself comes at a critical moment, questioning the possibility of a unified Syria.

Geneva's talks and Russia's withdrawal

The decision of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) to unite three major Kurdish regions in the north of Syria emerged while the Geneva peace talks were being held, having gained new impetus following the cessation of hostilities that has held - to some degree - over the past few weeks.

In addition, Moscow's decision to withdraw most of its forces from Syrian territory has also been regarded positively by the opposition.

The PYD's decision comes at a time when the Turkish government has escalated its attacks on PKK-affiliated groups in both Syria and Iraq following the multiple attacks in Ankara and Istanbul.

The Kurdish move is a timely response to the escalation in Erdogan's anti-PKK campaign on the one hand, and their exclusion from the Geneva peace talks on the other.

|

Russia remains silent on the viability of the Kurdish proclamation |  |

Both Assad and Erdogan have warned against the Kurdish manoeuvre under the pretext of retaining the unity of Syria. But while Erdogan has maintained US support, with the United States' refusal to endorse any decision for the formation of a federal system outside the Geneva peace talks, Moscow's position remains ambiguous.

Not long ago, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov had suggested that a federal solution to the Syrian civil war could be an option. The federal solution has also not been rejected by US Secretary of State John Kerry or the Assad regime.

But whereas they have set as a precondition agreement between the different Syrian factions in case the attempts at maintaining a unified Syria do not lead to fruition, Russia remains silent on the viability of the Kurdish proclamation.

Federalism and disunity

The harmful stalemate in the Syrian civil war has motivated international players to push for a settlement. While Russia does not appear to be enthusiastic over establishing an autonomous Kurdish region, Moscow's silence raises questions as to how amenable it really is to the developments instigated by the PYD.

In addition to Putin's obvious goal of spiting Turkey, Russia seems to be waiting for any developments that could follow from the Geneva negotiations.

|

Comparing the Syrian case with the development of an autonomous Kurdish region in Iraq is of significance |  |

The Geneva talks, however, appear to be barren so far, with little progress made on the key divisive issues. But while the negotiating sides continue their dispute over basic disagreements, the Syrian Kurds seek to take advantage of the deadlock in order to push for a federal alternative, and present it as a viable solution.

But the declaration of a Kurdish self-governing region has also been opposed by significant Kurdish parties. The Massoud Barzani-supported Kurdish National Council, which is taking part in the peace talks, has rejected such a decision in the absence of agreement with other Kurdish and Syrian factions.

|

|

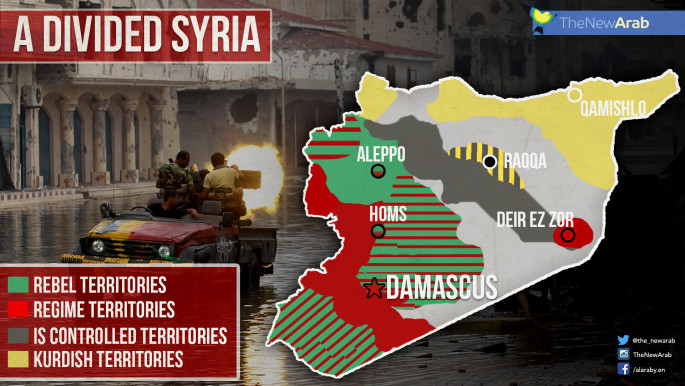

| [click to enlarge] |

Comparing the Syrian case with the development of an autonomous Kurdish region in Iraq is of significance.

In the Iraqi case, the move towards self-governance was initially the product of a bilateral agreement following a lengthy war between Kurdish militants and the old regime. On the other hand, such an agreement did not happen - and could not have happened - in Syria, in the absence of a legitimate side with which such a covenant could be established.

Given the widespread condemnation of the declaration of a Kurdish self-governed region, the successful implementation of such a solution remains extremely improbable.

Nevertheless, the Kurdish declaration also aims at thwarting any progress made in Geneva. The exclusion of the influential PYD from the peace talks has given the movement the opportunity to act independently of the other Syrian participants. In fact, for a while now, the Kurdish forces have been highly organised in terms of self-governance. This has been reflected in the political and military levels at which the People's Protection Units (YPG) has received support in the US.

What the Kurdish announcement accomplishes, therefore, is bringing to the forefront as a live option the idea of federalism if, as expected, the Geneva talks do not lead to results.

Whereas this could offer one way out of the current stalemate, it is doubtful such measures would or could lead to the reconciliation needed to move beyond the civil war.

While the Rmeilan conference reportedly included non-Kurdish populations, several insurgent groups have declared their intention to pursue armed resistance to prevent the realisation of their federal aspirations. The declaration of self-administration and the responses it has elicited can only serve to extend the crisis at hand rather than offering satisfactory means for political inclusion and transitioning from the state of war.

Karim Barakat is an instructor of philosophy in the American University of Beirut.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News