Who is losing the Nile?

"Egypt is a gift of the Nile!"

Schoolchildren the world over who have studied the history of the pharaohs know that quote from the great Greek historian and traveler Herodotus, who lived in the 5th century BC.

In the century before the birth of Christ, the Latin poet Albius Tibullus paid tribute to the river, for "along thy bank not any prayer is made to Jove for fruitful showers. On thee they call!"

And yet, this thousand-year-old blessing is under threat, and in Cairo specialists and civil servants alike - on condition of anonymity - admit that Egypt's struggle to retain control over the waters of one of the world's longest river is off to a very bad start.

Before the year is out, the construction on the Blue Nile of the huge Renaissance dam will be finished, and Ethiopia will be in complete control of the flow of its waters.

"We've lost," an Egyptian official reluctantly admits. "We were unable to stop them from building the dam; we couldn't get them to change any part of their plans, or to reduce its capacity. Our only hope, and it's a slim one, is that filling the reservoir will take longer than the three years planned by Addis Ababa."

Otherwise, Egypt is likely to experience water shortages, perhaps as early as next year. And in Cairo, people still refer to the more-or-less legendary episode at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, when Ethiopian King Dawit II threatened the Mamluk sultans with cutting off the flow of the Nile.

Use of the waters of the Nile is a complex issue, involving international law (how should the waters of a transnational river be allotted?), regional history (the many treaties signed over the years), and a rhetoric of the "inalienable rights" of the different parties and power relations between the riverside countries.

|

|

| Map of the Nile basin and Renaissance Dam [TNA/Agnes Stienne] |

At the risk of simplification, let's outline the basic elements of this dispute:

The Nile rises in Ethiopia as the Blue Nile, and in Burundi as the White Nile. The two join together at Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, with the former supplying 90 percent of the total volume of water. Since the beginning of the 20th century, Egypt has obtained - through various treaties - the recognition of its water rights. This is all the more crucial, as 97 percent of Egypt's water needs depend on the Nile, unlike the other riverside countries such as Ethiopia where there is plenty of rain.

Though these basic factors have always appeared immutable, they have now been overturned.

Firstly, the region has experienced a population explosion:

In 1959, Egypt had 35 million inhabitants, Sudan 11 million and Ethiopia 27 million. In 2016, however, their respective populations had grown to 95 million, 40 million (including Sudan and South Sudan, independent since 2011) and 102 million.

|

Water is becoming a rare and increasingly expensive resource |  |

The other riverside countries saw a similar boom. To this, we must add the intensification of livestock breeding which accounts for half of both the Ethiopian and Sudanese agricultural GNP and absorbs steadily increasing amounts of water, while rainfall is declining as a result of global warming.

Lastly, rapid urbanisation has also caused an increase in water consumption. Water, then, is becoming a rare and increasingly expensive resource while across the Horn of Africa, and the desert is gaining ground.

It is in this context that Ethiopia launched its Grand Renaissance Dam project on the Blue Nile. It will be the biggest dam in Africa, more impressive even than the Aswan High Dam, built in the 1960s by Egypt with Soviet aid as a showcase for the Nasser regime.

Read more: Egypt anxious as Nile-dam talks delayed amid Ethiopia chaos

Standing 175 metres high and 1800 meters long, the new dam's storage capacity is 67 billion cubic metres, nearly the equivalent of a year's flow of river water. The result of a unilateral decision, its construction by an Italian firm began in 2013 and according to Addis Ababa, it is two thirds finished. It will be able to produce 6,450 megawatts (MW) of electricity.

Hani Raslan, research fellow at the Al-Ahram Center for Political and Stategic Studies and one of the most qualified Egyptian experts on these issues, believes that the Ethiopian project is "mainly political":

"It is aimed at consolidating national unity in a country where power is monopolised by a tiny ethnic minority, the Tigrayans, who encounter much opposition, especially from the largest ethnicity, the Oromos."

|

|

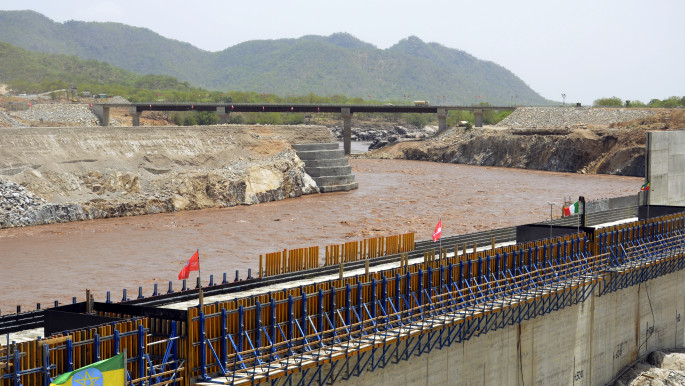

| The Blue Nile in Guba, Ethiopia, in May 2013, during its diversion ceremony. Ethiopia has been diverting the Blue Nile as part of the Renaissance Dam project [AFP] |

The Oromo held street protests at the very end of 2016, and early in 2017 when Addis Ababa accused Cairo of encouraging their rebellion. "What is the point of wanting to produce 6,000 MW of electricity," Raslan wonders, "when the consumption of Ethiopia and all its neighbours combined does not even amount to 800MW?"

A western expert agrees: "Economically speaking, as well as from an ecological standpoint, it would have been more rational to build several dams." The consequences of the construction of giant dams have long been debated and not only in Africa. As this specialist reminds us: "The dams retain the water but they also trap the sediment carried by the rivers and which serve to fertilise the soil."

But the Ethiopian government has invested all its prestige and authority in this dam, brought to bear all its domestic resources, and demanded forced contributions from the population. And nothing seems likely to stand in its way.

|

The Ethiopian government has invested all its prestige and authority in this dam |  |

"Ethiopia is behaving like Turkey," Raslan spits out, and coming from him this is no compliment: The relations between Egypt and Turkey have deteriorated since Abdel Fattah el-Sisi took power in Egypt in 2013.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan is accused by Cairo of backing the Muslim Brotherhood, the sworn enemies of the Egyptian regime.

Raslan was referring to the South-Eastern Anatolia Project (GAP) involving the great Ataturk dam and some 20 smaller structures which have partly dried up the Euphrates and the Tigris, causing water shortages in Syria and Iraq. Now it will be Egypt's turn to suffer a water shortage.

Faced with Ethiopia's determination and Sudan's support for Addis Ababa's position, Egypt has proven incapable of mounting a coherent strategy, wavering between an ultra-nationalist rhetoric - especially in the media, always ready to flare up over the Nile issue - and a public stance of willingness to cooperate which often borders on delusion.

Thus, on the occasion of the summit meeting of the African Union in January 2018, Sisi, flanked by the Ethiopian and Sudanese presidents, claimed that all the problems would be solved within a month:

"Egypt's interests are one with Ethiopia's and also one with Sudan's. We are speaking as one voice. There is no crisis, there is no more crisis."

At the same time, he withdrew his mediation request submitted to the World Bank a few weeks earlier to resolve the deadlock. In March 2015, a provisional agreement had already been signed between the three parties, which Sisi had approved against the advice of several members of his entourage, including his national security adviser, Faiza Abu el-Naga.

Twitter Post

|

In a region where there is no willingness to cooperate, where each of the three regimes favours a nationalist stance first and foremost, Egypt - though unwilling to recognise this - is up against a decline in its influence.

In the words of Nabil Abdel Fattah, another research fellow at the Al-Ahram center and a distinguished expert on Sudan, "our diplomatic capacities in Africa have been shrinking for decades; we depended on the United States and Europe.

"We neglected the major changes taking place on the continent and had no scholars, diplomats or military personnel who really knew Ethiopia. We have even proved incapable of resolving this impasse by activating the Coptic networks when the churches of both countries are closely connected."

And what about Sudan's policy shift, a country traditionally allied with Egypt? "The history of our countries' relations is very complex," Nabil Abdel Fattah explains.

"Sudan is a country which we occupied during half the 20th century and it became independent against our will. There is a kind of love-hate relationship between the two of us not unlike that which determines Franco-Algerian relations."

But time has passed and ties have weakened, and Cairo has neglected its neighbour to the South. On 30 June 1989, a coup in Khartoum brought Omar al-Bashir and his Islamists to power. "That regime has been in power for 28 years," an Egyptian diplomat observes, "and during all that time it has done all it could to sever the links between our two countries.

"It closed down the Egyptian universities in Sudan and fuelled hostility towards Egypt, especially among young people who hadn't known the period of good relations. Actually, power is in the hands of the Muslim Brotherhood who seek revenge for what happened in 2013."

|

If diplomacy fails, could there be a war? |  |

Nabil Abdelfattah explains. "A culture of exclusion has developed in Sudan," he said. "The Salafists have extended their grip on society, on young people, often with the help of Saudi Arabia."

Nonetheless, he does acknowledge the existence in Egypt of an anti-Sudanese racism, and admits that his country has often neglected the development problems encountered by their neighbour to the south.

One of the contentious issues, regularly raised by Khartoum, concerns the Hala'ib triangle in south-western Egypt - which Sudan has claimed for its own since independence.

"They call it an occupied territory," Raslan says with indignation, "and describe our army using the word misraili, which associates Egypt (misr) and Israel, and establishes a parallel between Palestine and the Hala'ib.

"They lost South Sudan, which has become independent and raise their flag over Hala'ib to distract from that."

Twitter Post

|

The two capitals frequently accuse one another of harbouring their neighbour's dissidents: The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and the Darfur rebels.

And yet apart from his ideological orientations, what characterises Omar Bashir, president of Sudan, indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes against humanity in Darfur, is his pragmatism.

For a long time he was allied with Iran, but in 2014 he broke with the Islamic Republic and joined forces with Saudi Arabia - which played a role in lifting American sanctions in 2017 - and sent several thousand soldiers to Yemen.

Even in Egypt, it is acknowledged that Khartoum's siding with Ethiopia on the Nile issue was a kind of realism: "Sudan realised that Ethiopia was going to win," an Egyptian diplomat explains, "and counts on reaping benefits from the situation, lots of free electricity."

He fails to mention the ecological fallout - but brandishes the unlikely possibility of the dam's collapsing "when Khartoum finds itself under thirty feet of water".

Already disputed by three countries, the Nile and the Horn of Africa have been taken hostage by the warring regional powers in the Middle East - Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey and Iran. And in this extremely complicated game of chess, Egypt finds itself rather isolated.

After a difficult period, their relations with Saudi Arabia have improved, but Riyadh is still providing indispensable economic aid to Sudan, which has just devalued its currency.

"They've paid the price of blood in Yemen, and since the Saudis are Bedouins, that matters for them," an Egyptian intellectual observes, with a hint of contempt.

Already enjoying the support of Sudan and the United States, who regard it as a key ally in the war on terrorism, especially in Somalia and the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia recently received Turkish support as well.

Its president, Mulatu Teshome, went to Ankara in February 2018 to meet with Erdogan. In November 2017, the Ethiopian prime minister had signed a major agreement in Doha for bilateral cooperation, and Qatar was even accused by the Egyptian press of financing the dam, a good example of fake news.

Ethiopia had cut diplomatic ties with Qatar in April 2008 following Al Jazeera's critical coverage of the situation in Ogaden.

|

Since 2013, Sisi has developed a nationalist, in fact a chauvinistic rhetoric |  |

If diplomacy fails, could there be a war?

"The next conflict in the Middle East will be over water (…) Water will have become a more precious resource than oil," Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who had just become UN General-Secretary, prophesied in 1992.

True enough, there is much sabre-rattling in the region and in January the Sudanese press announced the creation of a joint military force with Ethiopia, meant to protect the dam.

The Egyptian fleet is cruising in the straits of Bab el-Mandeb, playing its part in the Yemen war, but it could well become involved in a conflict with Ethiopia.

And Cairo has deployed troops in Eritrea, Ethiopia's bitter enemy with whom it fought a bloody war from 1998 to 2000.

"And yet," an Egyptian diplomat admits, "while our military superiority over Ethiopia is undeniable, a war scenario is unlikely. Egypt would be totally isolated. And the undertaking itself would probably not be as easy as our informant believes.

An Egyptian journalist adds: "For Sisi, it is preferable to wait until after the presidential election at the end of March."

But what will happen then? When the Ethiopians begin stocking billions of cubic metres of water next summer, and depriving Egypt of some of its resources?

Since 2013, Sisi has developed a nationalist, in fact a chauvinistic rhetoric; but when last year Egypt transferred to Saudi Arabia the islands of Tiran and Sanafir, where Saudi soldiers have just been stationed, there was much protest and a decline in Sisi's popularity, even among his most stalwart followers.

Is he going to let Egypt lose the Nile, the county's jugular vein for thousands of years?

Alain Gresh is the Director of Orient XXI, a journalist and expert in Middle East affairs. He is the author of 'L'Islam, la République et le monde', Fayard, 2014 among many others.

This article was originally published by our partners at Orient XXI.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News