Libya's peace summit promised to improve conditions for migrants. But will it deliver?

Failure to find a peaceful solution will only add to the misery of stranded migrants in the war-torn North African country.

The conference in Berlin had been presented as a first step in a political process towards peace, with world and regional leaders meeting in a desperate bid to end the long-running conflict in Libya.

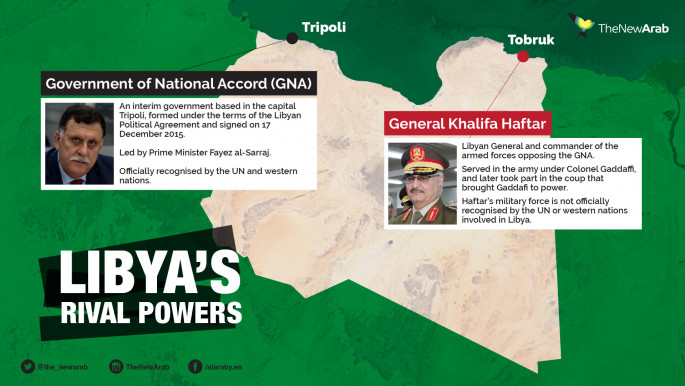

Leaders of both Libyan warring factions, strongman Khalifa Haftar and head of Tripoli's UN-recognised government Fayez al-Sarraj, also attended the event.

Compared to previous meetings on Libya, the focus this time was on getting external actors wielding influence on the warring parties to sign up to a plan to stop interfering through the provision of weapons, troops or financing.

Although the summit was intended to broker a ceasefire and make a fresh push for peace, just hours ahead of the meeting Haftar's troops raised the stakes by blocking oil exports from Libya's main ports to protest Turkey's decision to send troops to Libya earlier in January to bolster Sarraj's Tripoli-based government.

|

|

| Read also: Key Libya middleman Tunisia is left out of the Berlin conference |

A fragile ceasefire, backed by both Ankara and Moscow, that was put in place on January 12 is not holding, and the UN arms embargo has been reportedly violated.

Conclusions from the conference do not bring forth any new solutions to resolve the Libyan crisis, building upon the declarative documents on the principles and mechanisms of political settlement, previously agreed in Paris, Palermo, Abu Dhabi and Skhirat (the Libyan Political Agreement of 2015).

The conclusions are also consistent with the three-part action plan that UN special representative for Libya Ghassan Salame presented to the UN Security Council, consisting of persuading the parties to the conflict to end hostilities and enter a Libyan-led peace process under UN auspices.

The 55-point final communique outlines six "baskets" of activities, which are related to securing a ceasefire, implementing an arms embargo, resuming the political process, security and economic reforms, and respecting international human rights and humanitarian law.

|

The conference in Berlin has been presented as a first step in a political process towards peace, with world and regional leaders meeting in a desperate bid to end the long-running conflict in Libya |  |

In the penultimate chapter of the document, which is dedicated to the sixth basket, there is one critical point specifically concerning the refugee and migrant population that calls all parties "to end the practice of arbitrary detention" and urges the Libyan authorities to "gradually close the detention centres for migrants and asylum seekers".

Point 46 also requests "amending the Libyan legislative frameworks on migration and asylum to align them with international law and internationally recognized standards and principles".

"The call for the end of arbitrary detention and closure of detention centres is an important stance," said Marcello Giordani, Project Coordinator at the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD).

"Revising the Libyan legislation is absolutely fundamental, relevant Libyan actors are well aware that it needs to be adapted in order to fill the gaps in the sphere of migration and asylum," he added.

Making reference to regional conventions Libya ratified, the development expert emphasised that the North African country is "obliged to turn these ratified treaties into national law", which it has never done until today.

"The Berlin meeting doesn't add anything new but it sets out formally a series of actions that include the legislative question on migration and asylum, and the shutting of migrant detention facilities," Giordani noted.

Another point in the penultimate chapter asks to allow civilian access ("including internally displaced people, migrants, refugees, asylum seekers and prisoners") to medical treatment and humanitarian assistance, and to take action for the protection of the civilian population.

|

There are numerous informal detention facilities operated by armed groups and criminal gangs in the country, and GNA authorities do not have oversight of those 'unofficial' camps |  |

Lucas Rasche, Policy Fellow in EU Migration and Foreign Policy at Jacques Delors Centre, welcomed the move by signatories in Berlin to agree, at least on paper, to close migrant detention centres in Libya, though he is cautious about its implementation.

For such proposal to be applied, he explained, cooperation with those who run detention facilities is necessary, and access to these facilities is a prerequisite.

One major technical problem is the "partial access" UNHCR and humanitarian personnel have to detention camps across the country, the policy fellow said, which not only hampers the provision of humanitarian aid, but limits the interaction with local actors needed to facilitate closure of prison camps.

For Rasche, a shortcoming of the Berlin communique is that it does not envisage steps following the proposed closure of migrant prison facilities, which leaves migrants in very uncertain circumstances in a high-risk conflict environment.

"There is no contingency plan for what comes after detention. What will happen to migrants after they are freed? They won't be free of risk," he said, foreseeing that migrants will likely continue to experience violence, exploitation and extortion once they are out.

With regard to the pledge to fully respect international humanitarian law and human rights law, point 47 underlines the need to hold accountable all those who have violated provisions of international law, including in the areas of "torture and ill-treatment, human trafficking, and violence against or the abuse of migrants and refugees".

However, the Libyan context makes it very complicated to ensure legal compliance and accountability in many domains where the state is completely absent, given that there is not a "Libyan state" in the first place.

There are numerous informal detention facilities operated by armed groups and criminal gangs in the country, and authorities from the internationally-recognised government of Tripoli (GNA) do not have oversight of those "unofficial" detention camps.

"The Berlin conference was a diplomatic success, but it's too early to say how much it can actually change things for migrants and refugees in Libya," Rasche concluded, "the ceasefire is an opportunity to improve their situation besides that of Libyans".

On the other hand, according to the migration policy specialist, European and EU member states should make "greater commitment" by: taking refugees and migrants out of Libya "either via evacuation or direct resettlement" by means of responsibility-sharing and fair redistribution across different countries; and "reviving Operation Sophia", which was tasked originally as a search-and-rescue mission to save migrants off the Libyan coast.

Luca Raineri, Research Fellow in International Relations and Security Studies at Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies, noted that something "interesting" is the fact that the plea for the closure of detention centres was also undersigned by the EU and many European states.

"This de facto disavows the EU's strategy of migrant containment of the past several years," he argued.

|

|

| Read also: How Libya's crisis forced Algeria to come out of diplomatic hibernation |

In many instances, European governments have given proof of their hypocrisy in deploring the inhumane conditions migrants are facing in Libyan detention camps while essentially adopting a shared policy with Libyan authorities that sends migrants back to the conflict-ridden country, and exposes them to prolonged arbitrary detention, torture or death.

The researcher pointed to a control policy whose main tool has been the use of detention. "Detention centres have become a means to tackle irregular migration by the will of European actors," he maintained, "the real change in 'will' needs to happen in Europe first of all".

While acknowledging the importance of the accord reached in Berlin, which implies a significant policy that Europeans have signed up to, Raineri said it does not appear that European leaderships are taking a new direction in their "political will" required in order to translate their commitment into action.

"I think Europe hasn't carefully calculated the risk that a possible protracted battle for Tripoli may entail on a humanitarian level as well as in terms of forced migration flows," he anticipated. From his perspective, with the current escalation of the crisis, any of the Libyan militias, out of desperation, could decide to put pressure on Europe by "unlocking" the migratory route toward European coasts.

The scholar, who has a special interest in African security, stressed that with the ongoing humanitarian crisis involving migrants and refugees trapped in detention centres, their fate is particularly problematic as the conflict escalates in Libya.

Libya has been in turmoil since the overthrow of dictator Muammar Gaddafi, in 2011, turning into a battleground for rival proxy forces. With the ongoing chaos engulfing the country, Libya has become the main gateway in north Africa for refugees and migrants trying to reach Europe.

According to UN figures, there are over 40,000 migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in Libya who are stuck because of the fighting. Many of them wanted only to transit through Libya on their way to Europe, others including Libyans have decided to leave in search for safety. Around one million refugees, migrants and Libyans have been caught in the crossfire since 2011.

There are currently "more than 3,000 refugees and migrants being held in detention centres in Libya," based on data from UNCHR. Only last year, nearly 10,000 seeking safety in Europe were intercepted at sea by the Libyan coastguard and returned to detention camps where the horrific conditions experienced by African migrants and refugees have been widely documented.

Despite the UN arms embargo in place since 2011, efforts to implement it have failed for almost a decade with numerous external players accused of arming the warring sides in Libya's civil war.

Fighting has been mounting since General Haftar launched his offensive on Tripoli in April. Most recently Turkey agreed to send troops in to back the government in Tripoli against the eastern commander. There is a stark polarisation between the players who are loyal to the GNA and those backing Haftar.

|

According to UN figures, there are over 40,000 migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in Libya who are stuck because of the fighting |  |

Following the Berlin meeting, Alarm Phone, a project that established a hotline to support rescue operations, posted a critical tweet: "The Libya summit in Berlin has made it very clear: the different factions have no interest in ending the conflict. Both Libyans and migrants in transit will continue to be the victims of warfare and for many of them the Mediterranean will remain the only escape route".

On the occasion of the peace conference, UN chief Antonio Guterres issued a reminder of the dangerous consequences of a full-blown civil war which could lead to a "humanitarian nightmare", and leave the country vulnerable to "permanent division".

"Migrants and refugees, trapped in detention centres near the fighting, have also been affected and continue to suffer in horrendous conditions. This terrible situation cannot be allowed to continue," he also said.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi warned in a tweet on the eve of the summit: "Progress towards peace at the Libya summit in Berlin will also prevent further forced displacement of Libyans and allow for better support to stranded refugees and migrants. Failure will make humanitarian problems in Libya even more dramatic and intractable".

There are serious concerns that signatories to the accord will do little to abide by the commitments.

As hostilities show no signs of abating, and the Libyan theatre is becoming more complicated with increasing foreign interference, the situation for migrants and refugees who remain stuck in the country threatens to become even more dramatic.

Alessandra Bajec is a freelance journalist currently based in Tunis.

Follow her on Twitter: @AlessandraBajec

![libya migrants [Getty] libya migrants [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_345x195/public/media/images/B53B18D4-C3C2-4C38-B966-A92688B16AED.jpg?h=d1cb525d&itok=EEI8Bkil)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News