A step by step guide to Iran's presidential elections

Every four years, the world is unsure whether to bite its nails or roll its eyes at Iran's presidential elections.

On the one hand, nobody wants a president who will destabilise the region, or a repeat of the 2009 post-election violence. On the other, many believe that Iran's president has no real power and is just a figurehead for the Ayatollah.

Commentators from the West to the Middle East argue over whether Iran's time as an Islamic Republic is coming to an end, or if the new president will be doing more of the same.

But first, let's take a look at how Iran's president is elected.

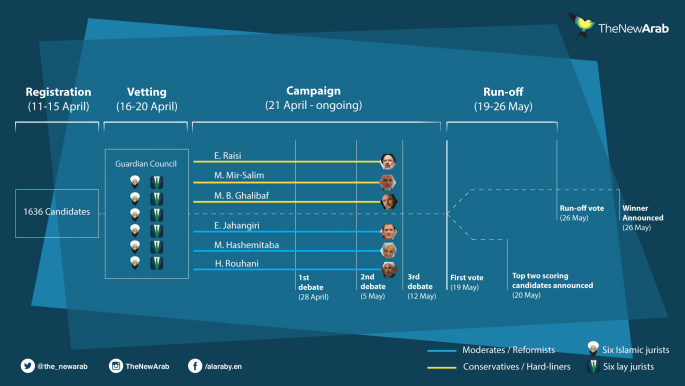

The election consists of four parts: Registration, vetting, campaigning and voting - which includes a possible second round run-off.

Vetting

The vetting part of the election is an important feature of Iran's political system. Interested candidates register their names for consideration by the Guardian Council - a body of 12 jurists (six Islamic and six lay jurists) - who are all essentially appointed by the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Both women and men can apply, although so far no female candidate has made it through the vetting process.

The Guardian Council has the authority to vet candidates running for political office before they're allowed to stand for election. This is based on a rather particular interpretation of Article 99 of Iran's constitution, which gives the Council a supervisory role in elections. In 1991, the Guardian Council determined that its constitutionally designated task to supervise the elections allowed it to decide who could run for president.

This interpretation, as well as the standards by which the Guardian Council vets candidates, has always been controversial, inside as well as outside of Iran: Critics say it gives the Council the power to ban any candidate it doesn't like, without justification, according to its own factional interests. It also doesn't seem to comply with the plain language of Article 99.

|

Of the more than 1,600 registered candidates, only six were approved by the Guardian Council |  |

In practice, this vetting process results in a very small fraction of candidates who register to run for president being allowed to actually stand for election. This year, of the more than 1,600 registered candidates, only six were approved by the Guardian Council. Even former presidents are not exempt from the Council's vetting power: Former Iranian President Ahmadinejad found himself disqualified this year.

He had registered to run for a third term in office, against the wishes of Ayatollah Khamenei, who likely used his influence on the Guardian Council to ensure Ahmadinejad's disqualification. This is a continuation of the rift that developed between Ayatollah Khamenei and Ahmadinejad while Ahmadinejad was president.

While there is a process that allows excluded candidates to raise objections to the Council's decisions, this, in practice, doesn't often result in reconsideration.

After the final candidates are announced, campaigning begins. The six candidates now running started their campaigns on April 20, after the Guardian Council disclosed the list of allowed contenders.

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

Round one

On election day, all Iranian citizens aged 18 or over (including women), whether living in Iran or not, have the right to cast their vote.

In total, there will be about 55 million eligible voters. Iranian citizenship passes through the father and is difficult to renounce: Among other requirements, the Council of Ministers must give you permission to lose your status as an Iranian citizen.

In practice this can be almost impossible, especially for people who haven't lived in Iran. Among other things, this means that many children of Iranian parents have never set foot on Iranian soil, and are still allowed to vote. They can do so at ballot boxes in around 140 different countries.

Voter turnout can be fickle; since the late 1990s, it has been somewhere between 60 percent (Ahmadinejad in 2005) and almost 85 percent (Ahmadinejad's second victory 2009, although these results are under dispute).

Hassan Rouhani won in 2013 with a turnout of almost 73 percent. A similar percentage of eligible voters is expected to vote on May 19, although this is hard to say for sure. Turnout seems closely correlated with the population's enthusiasm and belief that their vote actually matters based on the previous several years' political activities.

Round two

Similar to the French system, a candidate must secure more than 50 percent of the vote to win.

If no one gets a majority the first time around, the election proceeds to a second round between the two candidates with the most votes from the first. This year, the runoff will be held on May 26 if no candidate manages to get a majority in round one. Unless some candidates drop out in the next few days and endorse another candidate, it's very likely that there will be a second round.

After the election, the Guardian Council's role isn't over. The Council is allowed to nullify votes if it finds compelling evidence of fraud or irregularities.

Allegiances and favourites

Of course, this is how the election works in theory. Various groups such as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard try to exert their influence and prop up their preferred candidate. Supreme Leader Khamenei is also always rumoured to have a favorite (though this is almost never confirmed).

It's not uncommon for candidates with similar political backgrounds to drop out of the race and endorse a more popular candidate: This year, there's speculation that reformist Eshaq Jahangiri will drop out and support the more centrist incumbent, Hassan Rouhani.

The more conservative candidates may try to use the same tactic.

Keeping the peace

Regardless of the outcome, the regime's primary concern is that the elections don't proceed as they did in 2009, when there was a massive upsurge of post-election violence. The government cracked down heavily on protesters demonstrating against what they saw as an illegitimate victory by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

This severely undermined the legitimacy of the Islamic Republic both domestically and internationally. In between deciding whether to roll their eyes or bite their nails, some in the regime may well be tearing their hair out.

Behnam (Ben) Gharagozli received his BA with Highest Distinction in Political Science from UC Berkeley and his JD cum laude from UC Hastings College of the Law. While at UC Hastings, he served as Development Editor of the Hastings International and Comparative Law Review.

Follow him on Twitter: @BenGharagozli

Jon Roozenbeek is a PhD candidate at the Department of Slavonic Studies at the University of Cambridge. He studies Ukraine's media after 2014. Before coming to Cambridge, he worked as a freelance writer, editor and journalist.

Adrià Salvador Palau Is a PhD candidate in the Distributed Information and Automation Laboratory at the University of Cambridge. He has written several journalistic articles about politics and international relations. He is interested in how data science can be used to better understand political dynamics.

Follow him on Twitter: @adriasalvador

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News