Breadcrumb

Sinai's famed Zalaga camel racers defy militant threat

The race is a competition between the youthful cameleers of the Muzena and Tarabin tribes of South Sinai, as well as between each tribe's camel breeders.

While this event has been running since the early 1980s when Israel ruled the Sinai, the Bedouin have been racing camels here for hundreds of years.

The two South Sinai tribes of Tarabin and Muzena, who once took Israeli tourists on safari, created the race both as an additional attraction and as a way of reviving their own culture in the Wadi Zalaga valley.

"In the past they would race camels from Dahab area to Sharm el-Sheikh, or to Nuweiba - different places," says Mohammed Musa Muzena, a Bedouin resident of Dahab.

"But since the coast got more developed it's better to race in the mountains now - and Zalaga is a good place for a race."

Indeed it is - an unusually broad valley with space to accommodate both the racing camels and the multitude of off-road vehicles that accompany them - and a vantage point from which race-goers view the spectacle.

A social opportunity

For one day in January, the usually tranquil and remote wadi is transformed into a meeting place for all the tribes of Sinai, and some from further afield in Jordan and Saudi Arabia. The remote location makes it necessary to assemble the night before the race and camp under the desert stars, with people assembling at a central meeting place to announce the competitors and determine the winner's prize pot, donated by the two participating tribes.

Fires flicker all along the two sides of the valley, tucked into niches in the cliffs that offer some shelter from the icy wind, and the headlights of 4x4s and pick-up trucks cut through the darkness as people move around, visiting seldom-seen friends and relatives.

|

We are thinking of developing it into a larger festival in the future. It could be a cultural event with poetry, story-telling, markets - Sheikh Aisheesh Tarabin |

|

"Some people are more interested in going to meet friends than they are in the race," remarks Mohammed Musa. "But plenty really care about the race as well - it's a mix."

For some, coming from further afield, the meeting can last three days to a week. This year there are just a tiny handful of tourists, and it is clear that, whatever its origins, the race is now an overwhelmingly Bedouin affair.

"We are thinking of developing it into a larger festival in the future," says Sheikh Aisheesh Tarabin, one of the founders of the event. "It could be a cultural event with poetry, story-telling, markets - we will see."

A chaos of cars and camels

At 8am, the race starts, accompanied by the sound of gunfire and the blaring of car horns. Around 30 camels ridden by young boys aged between 10 and 14 sprint across the starting line and more than 100 off-road vehicles bearing the spectators surge forward, sending up a great cloud of dust.

The race takes place over approximately 30km, and it quickly becomes clear that as much as it is an opportunity for young boys to prove their prowess as camel-jockeys, it is also a chance for their older compatriots to show off their driving skills - as they attempt to outmanoeuvre each other and keep up with the camel pack.

Each vehicle carries gaggles of gleeful Bedouin, standing, sitting and clinging to the back or the roof, as the trucks lurch and buck over the uneven, rocky terrain. A few unfortunates quickly get bogged down in deep sand, and their passengers leap out to push them free, and then leap back aboard as the vehicles move off again at break-neck speed.

|

As much as it is an opportunity for young boys to prove their prowess as camel-jockeys, it is also a chance for their older compatriots to show off their driving skills |  |

A few engines expire from the stress and wheeze into silence, to be left behind in the dust as the race tears along the wadi.

After just a little time, the camel pack splits up into smaller groups which start to run between the speeding vehicles, seeking faster routes along the 1km-wide valley.

The cars now seek to overtake the racing camels to reach the finish line to see in the winner. Some truly wild driving ensues as they join the racers in jockeying for the prestige of being the first over the line.

Finally, most of the spectators are assembled, lining the hill-tops to greet the winner - a Tarabin this year for the first time in four years, followed by four Muzena camels at intervals of a few minutes each.

The response from the crowd is fairly muted, with the only whooping coming from the handful of foreign spectators, while the Bedouin stand in silent satisfaction, with a few expressing themselves by firing guns into the air as the trophy - a gold cup with a seemingly out-of-place footballer on the top - is awarded to the winner.

Military tensions

There was some concern this year as to whether the race would be able to take place at all, with rumours circulating that the military were going to seize people's vehicles, since it is generally forbidden to drive through the desert at this time - and traffic is supposed to be restricted to roads for security reasons.

Restrictions on movement have increased in the Sinai since the explosion aboard Russian Metrojet Flight 9268 on 31 October, which killed 224 people and was claimed by the Sinai branch of Islamic State, formerly known as Ansar Bait al Maqdis - a militant group that emerged after the 2011 Egyptian revolution to attack Egyptian military targets in North Sinai.

"They will ban us from riding camels soon, and then donkeys. I hope they will forget to ban cows because maybe then we can get some benefit from them," remarks Sheikh Aisheesh Tarabin ironically.

"It's about a lack of trust - the army don't trust the Bedouin."

These doubts stem from the history of the region and perceived ethnic and political differences between the Sinai Bedouin community and the Egyptians of the Nile River Valley.

|

|

| The race is an opportunity for young boys to prove their prowess as camel-jockeys [Ziyad Abu Haroun] |

Sinai was invaded and annexed by Israel from 1967 to 1982, when it was returned to Egyptian rule under the 1979 Land for Peace deal.

Since then, Egypt has sought to develop the region and incorporate it into the modern Egyptian state - often ignoring the rights or wishes of its Bedouin residents and effectively colonising the area with Egyptian business tycoons and their workers.

In addition, there is a strand of feeling from within the Egyptian political establishment that blames the Bedouin for not doing more to resist their Israeli colonisers and brands them as collaborators. Perhaps as a consequence of this, the Sinai Bedouin remain an impoverished and marginalised sector of Egyptian society.

"It's all bad politics," remarks Sheikh Aisheish. "We refused Israeli ID cards in the 1970s, even though that meant we could never get permits to build. In 1967 when the Egyptian army were fleeing from the Israelis, we even gave them our clothes so they could hide among us. Numerous times the Bedouin have proved they are loyal Egyptian citizens. But this is not remembered."

Things have gotten particularly bad in North Sinai in the post-revolution years, as the government has cracked down on the smuggling tunnels that link Egypt to Gaza and demolished thousands of homes in Rafah, as well as stepping up operations against militant groups operating in the area.

Human Rights Watch say that the campaign is harming thousands of civilians and risks doing more harm than good: turning people against the government.

"The Egyptian authorities provided residents with little or no warning of the evictions, no temporary housing, mostly inadequate compensation for their destroyed homes - none at all for their farmland," Human Rights Watch said in a report issued in September 2015.

"Destroying homes, neighbourhoods and livelihoods is a textbook example of how to lose a counter-insurgency campaign," said Sarah Leah Whitson, the organisation's director in the Middle East and North Africa.

|

|

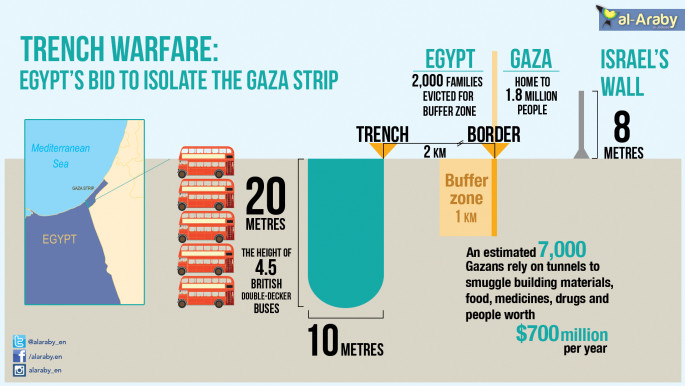

| Egypt's trench warfare in Sinai [Click to enlarge] |

"When the militants arrived in North Sinai the Bedouin sheikhs offered to help the army get them out" says Sheikh Aisheesh.

"Their help was refused and instead, the army turned on the Bedouin. Now some of the Bedouin have started joining the militants - people whose homes were destroyed and lost everything. But why did they do this?"

Since journalists and human rights monitors are not currently permitted to enter North Sinai, it is hard to ascertain a clear picture of the situation there.

Gold and silver don't fall from the sky

"I see an uncertain future in front of my people," Sheikh Aisheesh Tarabin says, staring into the distance.

"It could be war through all the region. I would say that the key is Palestine - until this is solved all the region is in danger of exploding. But perhaps there will also be a war between Sunni and Shia in the future, and then we will all be engulfed."

Against this backdrop, it is perhaps significant that the Zalaga Camel Race took place this year, despite the threats.

"The race reminds us of our roots - of who we are as Bedouin people. We have a saying that gold does not fall from the sky, nor silver. It means that everything we need comes from the land and it is to the land that we should turn now," he continues.

"Even if we know that the government will sell the land of Sinai, if they leave us a little to work with we can support ourselves. I started to farm eight years ago to grow food for myself and my family, and many others are doing the same now.

Read more of Alice Gray's reports here.

![Anthony Blinken speech [Getty] Anthony Blinken speech [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/media/images/6263436E-8ACD-4D3C-9055-25A7BE79DD5A.jpg?h=d1cb525d&itok=fLHmHCRG)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News