From the Sahrawi refugee camps: Polisario prepares its resistance

Last year, 28 African states submitted a motion to Idriss Deby, Chairperson of the African Union, demanding the suspension of activities within the organisation by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic.

Fifteen of these states were former supporters of the Sahrawi cause. This political manoeuvring heralds Morocco's return to the African scene, and the Moroccan state is likely to go further in its attempt to silence separatist voices.

Thomas Vescovi visited the refugee camps of Tindouf to find the Polisario Front preparing its response.

African states under pressure from Morocco

At the airport in the town of Tindouf, 1,400 kilometres south west of Algiers, protocol is strictly observed. Jeeps bearing the logo of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) wait for the handful of volunteers heading for the camps.

The convoy is escorted through the town of 47,000 inhabitants by Algerian police and military vehicles. A few kilometres beyond the last house, a checkpoint in the desert marks the transition: The escort vehicles become those of the Polisario Front, the authority officially in charge of the Sahrawi refugee camps.

Abeida Cheikh is the wali of the Smara camp, which houses around 50,000 people. After the usual pleasantries, the conversation turns to Morocco rejoining the African Union (AU), "we should see it as an opportunity, it means we'll be able to criticise Moroccan policy with representatives of the Kingdom present".

This is the official line of Polisario, keen to frame the Moroccan return as a victory, "When he's sitting alongside Brahim Ghali, the president of SADR, Mohammed VI will de facto be obliged to accord him some legitimacy."

|

|

| A Sahrawi refugee prepares tea at the Sahrawi refugee camp of Dakhla 170 kms to the southeast of the Algerian city of Tindouf [AFP] |

The reality is more complex. Since 2000, nearly 30 states that previously supported SADR have chosen to end their relations with it.

With a population predominantly under 30, the role of young people is central to every debate in the Sahrawi camps. Zein Sid Ahmed is Secretary General of the Sahrawi Youth Union, also known as UJSARIO.

Tasked since the 1991 ceasefire with preparing young activists for the fight to liberate their territory, these days it is more concerned with intellectual and political education.

For Sid Ahmed, the situation is of great concern: In a region criss-crossed by drug routes, and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQMI) threatening state stability, it is impossible for Sahrawi youth to remain unaffected. "Our young people are particularly vulnerable," he says. "They have three valuable qualities: They're educated, they're adapted to the desert climate, and they know the terrain."

The only way to prevent thousands of young people from responding to the calls of drug and extremist networks, and to quench their thirst to take up arms, is to find a political solution.

Sid Ahmed is in no doubt about the urgency. "There are only two options. Either we get justice through a referendum on the status of Western Sahara, or criminality and terrorism will win."

A drip-fed people

The internet and smart phones might have brought new ways of thinking to the camps, but both living conditions and economic prospects remain bleak.

The Sahrawis are entirely dependent on aid, as agricultural production is impossible on the desert land. Once a month, the World Food Programme (WFP) distributes food. Water tankers come to fill up the reservoirs in front of every house. A year ago, Algeria installed electricity pylons to serve the camps.

|

The only way to prevent thousands of young people from responding to the calls of drug and extremist networks, is to find a political solution |  |

Since the ceasefire, the main challenge for Sahrawi families has been accessing economic capital of their own. The men are allocated work according to their experience and training. Because basic needs are met for free, most activities are unpaid or very poorly paid. Many Sahrawis therefore opt to work in the sectors that do allow for the circulation of cash, notably transport and commerce.

In the camps, Mercedes 300D and 190E cars, imported cheaply from Spain, rule the roost. The other option is seeking work abroad. Hamoudi Thaleb left the Smara camp several years ago to work in Spain, Italy and France. When he returns, it's to help his family. At the moment he's working every day to reinforce the foundations of their home to prevent the sand from entering.

The camps all have a similar feel. As we pass down the sand and stone alleyways, the Sahrawis - used to seeing Spanish people - greet us with an "hola!" The children are more pragmatic, calling "caramelo?" The women wear the melhfa, a large piece of fabric that covers the whole body, along with woollen gloves and socks to protect them from the sun.

|

Young Sahrawis say they suffer from discrimination in foreign capitals because of their skin colour |  |

In the grocery shops, alongside light-coloured hair dyes and essential oils, are products for lightening the skin. Ali M, a young Sahrawi, explains the cult of fair skin: "I'd like to have skin as white as yours. I'd rather get sunburn than darker skin. With your skin, I could go wherever I wanted without being discriminated against, talk to anyone without any problems."

The young Sahrawis say they suffer from discrimination in foreign capitals because of their skin colour, notably in Algiers, where, along with the Algerians from the Sahara, they are easily distinguishable from the lighter-skinned people of the coast. The region's colonial heritage is alive and well.

Tackling Moroccan propaganda

Young biologist Mohamed Alkehal speaks of his greatest frustration - the image of the Sahrawi people presented to Europeans by Morocco. "They say we're here because we've been kidnapped by the Polisario. That's not true. We're here because our land is occupied. We're already in exile."

One after the other, the young Sahrawis express their distress at the lies told by the Moroccan state.

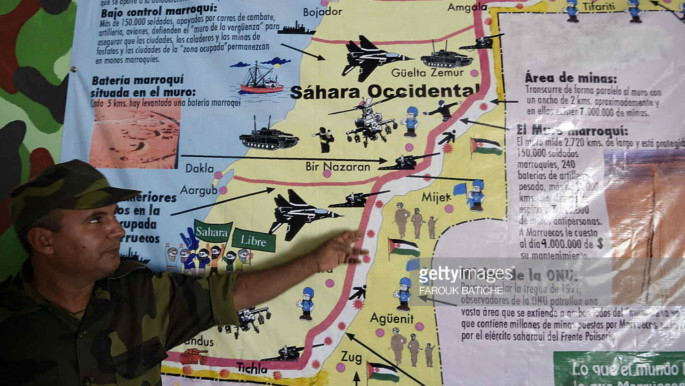

|

|

| A Polisario Front member shows a map of Western Sahara displayed at the People's Liberation Army museum [AFP] |

"Lots of Sahrawis have left the camps to live elsewhere," explains Alkehal. "But it's not easy for us to get visas. European embassies are already reluctant to give visas to Africans, never mind those living in Saharan refugee camps."

The Moroccan government is aware of the dissatisfaction of Sahrawi refugees and tries to persuade them to return, "we have to go to the Moroccan embassy in Nouakchott, in Mauritania. They ask us to sign documents recognising the sovereignty of Morocco over Western Sahara and declaring our allegiance to the King. If we do that, we can access financial aid to settle and find accommodation."

While some accept the blackmail, there are plenty of anecdotes about heroes of the cause who gave the Moroccan funds to their Sahrawi families, or sold the accommodation provided by the authorities and returned to the camps with large sums of money.

Weddings are a time for new connections. Sahrawi ceremonies take place in and around a large tent erected specially for the occasion. Inside, the women dance and sing. Outside, the men talk. The unmarried men steal looks at the unmarried women, who make furtive trips outside.

The presence of a European, a French man at that, creates a stir. A small crowd forms, and a discussion begins. The youngest people all say they want to take up arms again. "What use are we here?" asks one. "We've already had lots of martyrs, but all young Sahrawis are prepared to offer more. Our cause must be heard again."

|

The youngest people all say they want to take up arms again. 'What use are we here?' |  |

The schools in the camps are teaching new generations to carry the torch for the Sahrawi cause. Portraits of historical leaders Mohammed Bassiri and Moustapha Sayed Al-Ouali hang alongside those of Brahim Ghali and of Aminatou Haidar, a well-known Sahrawi activist living in the occupied territory.

Mohamed Mouloud, SADR's Education Minister, emphasises the importance of education to the Sahrawi struggle. "When we were at war, we had to educate thousands of children in the refugee camps, with no equipment or materials. Now we have between five and seven schools per camp. We've developed our own curriculum, we produce our own textbooks. We've just opened a teacher training centre. In the future we hope to build an archive."

A society dependent on humanitarian aid, SADR's budget comes entirely from external partners. The government's own funds are minute, so each ministry must build up what it needs from aid money and international partnerships.

"Seven percent of the partnerships between SADR and foreign institutions are focussed on education," says the minster. "They allow us to buy equipment and renovate some of our schools." The rest of the government's budget goes on food (50 percent), buildings and civil engineering (21 percent), and water management (8 percent).

Guaranteeing human rights for all Sahrawis

The Polisario claims to be the political party that represents the entire Sahrawi population, but what of those who hold different views? Abba Salek is President of the Sahrawi National Human Rights Commission (SNHRC). "We defend freedom of speech; every Sahrawi is at liberty to criticise the President or the decisions of SADR," he explains.

"However the development of other political parties would risk diverting us from our main objective, which is obtaining a referendum on self-determination and the liberation of our land." He promises a future Sahrawi state that is a democratic, multi-party republic, but this is no more than a promise. Looking at the evolution of other major political movements for decolonisation, it would seem sensible to remain cautious.

|

The Polisario claims to be the political party that represents the entire Sahrawi population |  |

The SNHRC has had observer status at the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights since April 2016. Salek is currently preparing files to expose actions by the Moroccan authorities to the African Union (AU).

The SNHRC is recognised by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights in Geneva, and includes among its partners the Moroccan Human Rights Association, which helped it to obtain files on Sahrawi prisoners, notably the 24 defendants of Gdeim Izik.

The Association of Families of Sahrawi Prisoners and Disappeared was formed in August 1989 to support the families of political prisoners and the disappeared, individuals arrested unofficially by the Moroccan state. Since its creation, it has investigated the cases of more than four thousand people.

| Read more: Trump victory sparks optimism in Western Sahara | |

The association's president, Omar Lahcen, says almost 500 Sahrawis are still considered disappeared. He points out that the tactic is used not just against the Sahrawi people, but against all opponents of the King of Morocco, including Mehdi Ben Barka, who was kidnapped and tortured to death in France, and whose body was never recovered.

The association has video footage of violence towards Sahrawi activists by the Moroccan security services. The images are unambiguous: Gatherings violently dispersed, activists humiliated in the street, women pushed and their veils ripped off and young people beaten up and thrown by the roadside in the middle of the desert.

The new faces of the Sahrawi cause

While the political heritage of SADR and Polisario remain powerful forces, a distinct new generation of Sahrawi activists is emerging. The organisation Non-Violent Action (NOVA) Sahara Occidental is a key player. It has around a hundred members, both in the camps and in occupied Western Sahara.

Abida Bouzeid, a charismatic and determined young activist, has been its president since 2014. She says "we want to channel the anger of the young people in the camps into large-scale political campaigns to counter Moroccan propaganda."

She declares herself independent of the Polisario, and speaks a language of action that has been less evident in the Sahrawi political movement. NOVA offers training in communication techniques and non-violent action to groups of young volunteers. It was recently engaged by SADR to train its soldiers in international humanitarian law.

|

'We want to channel the anger of the young people in the camps into large-scale political campaigns to counter Moroccan propaganda.' - Abida Bouzeid, Presdient of The organisation Non-Violent Action (NOVA) Sahara Occidental |  |

In 2016, Bouzeid was invited to speak in France. She says she was "shocked" by the lack of awareness of the Sahrawi cause amongst the French political classes, as well as by the weakness of international solidarity networks compared with others. "We attract less media attention than other causes because we lack sensationalism," she says. "We no longer have bombardments or military clashes, which is a good thing, of course, but it means our struggle has been marginalised."

NOVA now wants to mobilise young Sahrawis for important peaceful battles: The welcoming of international political and trade union delegations, the spreading of activist messages on social media and awareness-building among international artists.

With many young people expressing a desire to take up arms, non-violence is a choice some might not want to make. Bouzeid is firm: "We don't have a choice. A peaceful society cannot be constructed through violence. We need to reaffirm the fact that the Moroccan state has always been the entry point for the imperialist and neo-colonial tendencies of France and the United States in Africa."

French representatives notably boycotted Bouzeid's speech to the UN Security Council in March 2015. However in December 2016, she was part of the Sahrawi delegation at the 4th Maghreb Social Forum on Migration in Tangiers, on a visa organised by Oxfam.

She was able to make connections with Moroccan student organisations and to question the Moroccan government's rhetoric about her people. "We're not angry with the Moroccan people, but with their government. Africa is a huge continent; there's room here for all of us." she told the forum.

Thomas Vescovi is an author, teacher and researcher in contemporary history.

This article was originally published by our partners at Orient XXI.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News