Red lines and shrinking liberties in Morocco

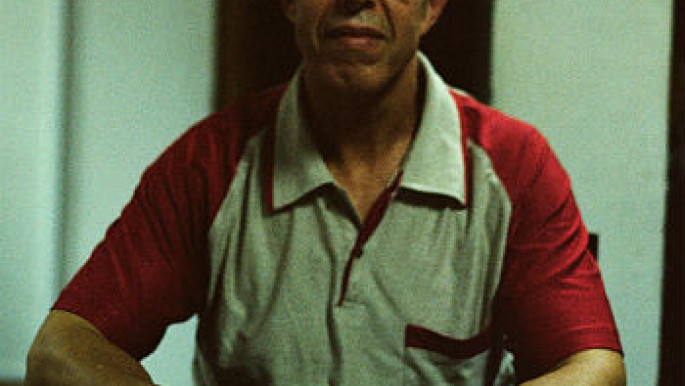

In a windowless room, Mohamed El Boukili seems small against the towers of paper that lean against the walls. A member of the Moroccan Association for Human Rights (AMDH), he complains of a crackdown on rights groups in the country.

"Until 2013, it was OK," he says, in his office in Morocco's capital, Rabat. "The state tolerated our existence and our reports. But in 2014, Morocco changed. Now, the state is going backwards. We are suffering a lot."

Press freedom has also suffered. Seven journalists and activists face trial in January; accused of "threatening the internal security of the state" after they organised training for citizen-journalists.

Another journalist, Hicham Mansouri, was imprisoned for ten months on adultery charges in a case that rights groups say is "politically motivated".

"We have a democratic façade," says El Boukili, behind clear-rimmed glasses. "But all the power is in the hands of the king."

The restrictions are having a serious impact on AMDH's work.

The authorities refuse to register the organisation's local bureaus. By not accepting registration documents, the offices are left in legal limbo - operating without permission.

For El Boukili, it creates a sense of unease. "This means the authorities could come to a meeting and say 'this is illegal'. We are waiting for them to use this card."

They have also been blocked from hiring venues for press conferences and workshops.

"We used to rent public places in hotels but when we started to publicise these events, the venue would cancel, saying they were not allowed to host us," El Boukili said. "We can't go to any hotels now. We are obliged to organise in a small room in our office. But for workshops, we need a larger space. The impact of this means our activities are shrinking."

Amnesty International has also faced restrictions on the venues it can hire.

Back in 2014, the organisation's Morocco branch rented a conference centre for its summer youth camp, but when participants arrived, they were refused entry. The venue director said he had been forbidden from hosting the event.

|

What we didn't realise at the time was the space for human rights scrutiny was shrinking |  |

Later in 2014, Amnesty researchers were denied entry to the country and in June 2015, two Amnesty staff were expelled. In both cases, they were observing the situation of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on the northern border.

|

|

| Mohamed El Boukili remains defiant [Frances Bakewell] |

Sirine Rached, a researcher for Amnesty in North Africa, says we can only speculate why the situation changed in 2014.

She points to Amnesty's global campaign on torture that ran from 2014, finishing earlier this year.

"As part of that campaign, Amnesty International made recommendations to Morocco on how to integrate anti-torture safeguards into criminal procedure, which we still hope will be taken on board," she says over the phone.

"But what we didn't realise at the time was the space for human rights scrutiny was shrinking."

The turning point came later for the US-based Human Rights Watch. In September 2015, the organisation received a letter demanding it suspended activities until a meeting could be arranged to discuss the organisation's "bias".

Although that meeting took place in March 2016, the suspension remains in effect.

"There was no warning that this was coming," says Eric Goldstein, deputy director of Human Rights Watch's Middle East and North Africa division.

"Morocco hasn't explained why [the crackdown on human rights organisations] is happening now but my sense is that Morocco feels emboldened by its own performance since the Arab revolts began in 2011, relative to the trajectories of other countries, and feels it can stifle, without paying much of a price, those whose reporting undermines its narrative that human rights are steadily improving in Morocco."

While the 2011 Arab Spring saw leaders in Egypt and Tunisia toppled, Morocco's monarchy side-stepped any existential threat by promising more powers for the country's parliament.

Oxford University's Michael Willis, who specialises in Maghreb politics, says that Morocco "has been surprisingly aggressive to international organisations".

|

There are a range of opinions within the Moroccan regime, but hardliners seem to be winning out |  |

He referred to an incident in May, when Morocco summoned the US ambassador in response to the State Department's 2015 human rights report which the kingdom denounced as "inventions and lies".

"I'm not quite sure who's making these decisions," said Willis. "To see it as a well thought-through policy is a mistake. There are a range of opinions within the Moroccan regime, but hardliners seem to be winning out."

The Moroccan government's Ministry of Communications did not respond to The New Arab's request for comment.

Willis believes the crackdown on human rights organisations is, in part, designed to protect the country's image as a liberal state. It does this, he says, to stifle a repeat of 2011's Arab Spring and to gain as much support as possible in Europe and North America.

"Morocco's main objective for the last 40 years has been its claims on the Western Sahara," says Willis. "It believes it may achieve this claim, if it can uphold this image."

But to maintain the perception of a liberal state, the kingdom has created "red lines" that activists and rights groups know will provoke authorities, if crossed.

"Red lines in Morocco are defined in law and include criticism of the royalty, criticism of Islam or anything that would be seen as threatening territorial integrity - including advocating the self-determination of Western Sahara," says Amnesty's Rached.

Organisations that avoid red lines can continue their work, undisturbed by the authorities. "We've never had an issue with restrictions," says Stephanie Willman Bordat, founding partner of MRA, a Rabat-based women's rights group.

"Violence against women is not one of the red flag issues."

For AMDH, it is a different story. Back in his basement office, El Boukili makes a direct link between they work they do and the restrictions they face: "When we produce a report about people dying under torture for example, it spoils the image that Morocco is trying to sell abroad."

Despite difficulties, El-Boukili says AMDH will not compromise on its values. "We will remain critical, otherwise we should close," he says. "We cannot shut our eyes to the abuse of human rights."

Morgan Meaker is a journalist specialising in human rights. Follow her on Twitter: @MorganMeaker

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News