In Kashmir, patients suffer as pharmacies run out of drugs

On September 12 Sofiya travelled around 10 kilometres by foot to get insulin. "I was running out of insulin. I went to different medical stores in my village but they didn't have insulin availability," Sofiya told The New Arab.

A pharmacist, where Sofiya regularly buys medicine for herself, had advised her to go to the main town of Kulgam district and try to find insulin from there.

"I took a risk and went to the main town where all the shops were closed. Gun-toting paramilitary troops were deployed along the roadside," Sofiya said. "After searching for hours I managed to get insulin from one of the pharmacies."

Sofiya was relieved when she got insulin after a hectic travel but she is concerned about the future because of the ongoing clampdown.

"Today I managed to get insulin but what will happen to me and other patients of Kashmir tomorrow," Sofiya said, sighing.

"Kasheer Karikh Khatim (Kashmir has been destroyed)," Sofiya added.

|

|

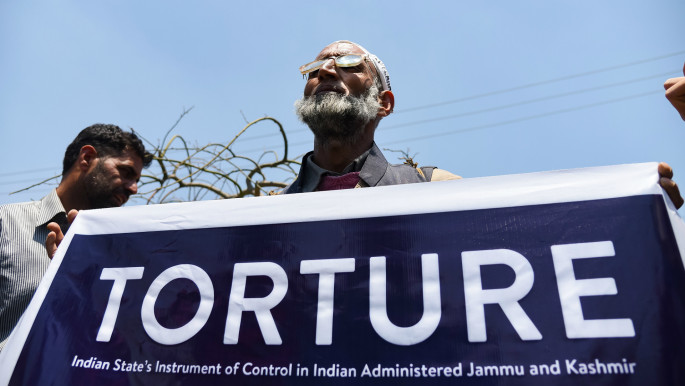

| Read also: Gory tales of torture in Indian-administered Kashmir |

Around 50 days have has passed since India removed Kashmir's autonomy and put the disputed territory under clampdown. Pharmaceutical stores in most of the areas are still running out of medicine with owners citing many reasons, ranging from communication blockade to restrictions and transport unavailability.

Rejecting the government claims that there is no shortage of medicines in entire Indian-administered Kashmir, pharmacists said the situation is totally different on the ground. In some cities pharmacists claim there is 30 percent medicine shortage while in villages the shortage is 50 percent or even more.

"Communication blockade and transport unavailability are major reasons behind the shortage of medicines. We have a 70 percent to 80 percent shortage," said Abdul Rafi Pandit, a member of medical association Yaripora, Kulgam. "There is an absolute shortage of psychiatric and lifesaving drugs like insulin, anti-rabies and so on in our area."

Outside the sub-district hospital in the Yaripora area of Kulgam around 15 pharmacies are running. Owners said when a patient comes with a prescription card to a particular pharmacy, they collect medicines for him/her from nearby stores.

"We try hard that the patient should not suffer under current circumstances. We have made this strategy to collect the prescribed medicines from nearby stores," said Mohammad Altaf Dar, a pharmacist. "Most of the times still the patients don't get 100 percent of the medicine they need."

Every day, pharmacists said, they have to send back at least 50 to 70 patients without their medicine and most of the time they provide patients with substitute drugs.

In the militancy stronghold district of Shopian in South Kashmir most medical stores are still closed, only a few medical stores remain open near the district hospital.

"We opened our shop one month after the abrogation of Article 370. There were strict restrictions in our area. It was difficult for me to travel six kilometres from home to shop every day," said Mohammad Issac, who runs a pharmacy outside the district hospital in Shopian. "We have a 30 percent shortage of medicines."

|

Sometimes we go to the Srinagar and return empty-handed |  |

Mohammad Ramazan Shah, 80, went to buy a medicine for her wife who is suffering from hypertension.

"After searching for hours from one medical store to another, I got a substitute drug. I don't know what will happen to my wife when she will take this drug," Ramzan told The New Arab. "We can’t even contact a doctor who has prescribed drugs to my wife because of the communication shutdown."

In the Anantnag district, pharmacists have refused to talk with the media as they don't want their name to be published in any organisation because of the fear of reprisal.

"Definitely! There is a shortage of medicines," one of medical store owners said. "A few days back under complete shutdown I went to Srinagar but they didn't have the medicine available."

Owners said they used to call or send a message to their distributors in Srinagar, the region’s main city and give them the order of medicines but the ongoing enforced ban on communication put them in trouble. "Sometimes we go to the Srinagar and return empty-handed," said a pharmacist.

Zubair Ahmad Wani, 28, a resident of the Anantnag district, searched a whole market on September 14 to get a medicine for his ailing mother. "There is a shortage of medicine. I felt it when my own mother ran out of drugs. I got the medicine only after searching it in the whole city," Zubair told The New Arab.

Surrounded by mountains, Indian-administered Kashmir is a region known for lush green valleys, dense forest and lakes. The disputed territory is wedged between two nuclear arch rivals – Indian and Pakistan. Both the countries claim the region in full but only controls its parts. In the late 1980s armed insurgency broke out in Indian-administered Kashmir against the Indian rule.

The death toll has already surpassed 70,000 while tens of thousands of others have been subjected to enforced disappearance and torture. Armed rebels want independence from India or merger of territorywith Pakistan and are receiving an overwhelming support from the most of the population.

On August 5 Indian central government revoked Kashmir’s special status and scrapped the constitutional provision that forbids outsiders to buy land in the Muslim majority disputed region.

Both the pro-Indian prominent leaders and secessionists are either under house arrest or detained in different jails. Though the authorities have lifted the restrictions in most parts, the deployment of paramilitary troops remain on roads.

Educational institutes, shops and private industries are shut. Traffic is off the roads. All forms of internet service and mobile calling are barred, causing common people to face hardships every day.

According to the reports, tens of thousands of youth have been detained and sent to different jails across India and scores of people have been subjected to torture.

* name changed due to fear of reprisal by the state

Aamir Ali Bhat is a Kashmir-based freelance journalist who reports on human rights abuses, culture and the environment. He writes for The New Arab, Kashmir Ink and Free Press Kashmir.

Follow him on Twitter: @Aamirbhatt3