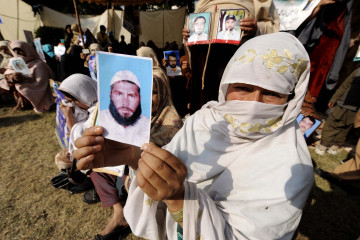

“It’s been 9 years. In these 9 years, there has been no Eid for us, no happiness, no good days, no nice clothes. Whenever there is something to celebrate we wonder what condition our brother is in, whether he is okay, whether he is sick, whether he has eaten,” said Sultan Mehmood, brother of disappeared Zahid and Sadiq Amin, at a rally in Islamabad organised by Defense of Human Rights Pakistan.

For decades, certain segments of Pakistani society have faced an epidemic for enforced disappearances.

In Pakistan’s peripheries - like Balochistan, North Waziristan, and the former Federally Administered Tribal Area - military-backed enforced disappearances and illegal abductions have been an ongoing phenomenon to restrict nationalist resistance movements.

These have led to high tensions between the country’s centre and peripheries. Many Baloch and Pashtun activists have been missing for years with no news regarding their well-being.

"Members of nationalist, separatist, and leftist movements have historically been the most likely targets of the state-sanctioned repression of civil liberties and enforced disappearances"

Despite multiple protests and social media campaigns, the percentage of missing people that find their way back is negligible in comparison to those whose whereabouts remain unknown.

Instead of celebrating its ethnic and cultural diversity, state insecurity and political instability in Pakistan has translated into an ethnocentric national policy against two of the oldest ethnicities in the region: Pashtuns and Baloch.

Members of nationalist, separatist, and leftist movements have historically been the most likely targets of the state-sanctioned repression of civil liberties and enforced disappearances. In their search for their loved ones and fight for justice, families have had their voices silenced and their rights squandered.

Pakistani authorities have yet to ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (CED), published in 2010 bringing into question the resolve of the state in eliminating the practice.

As per the data available through the state’s own Commission on Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances (COIED), more than 8000 people have been victims of illegal abductions since 2001.

While a majority of these cases continue to be under investigation, there is little relief to be found for the families of the missing persons.

Imaan Mazari, a lawyer and human rights activist, explained that the commission is used by the courts as a convenient way to digress from providing real answers.

“This is the most disgusting abdication of responsibility by the Constitutional Courts because the COIED is nothing more than a bureaucratic post office. Its proceedings are a mere eyewash and prolong the agony of the families of the disappeared,” she said to The New Arab.

|

|

“The Joint Investigation Team (JIT) within the COIED structure comprises representatives of the same intelligence agencies that are forcibly disappearing people in the first place. Hence, often what families face is a categorisation of the case from the JIT as a ‘voluntary disappearance’, thus unfairly obstructing their access to justice,” Mazari continued.

After a 7-day sit-in organised by Voice of Baloch Missing Persons in February 2021, Imran Khan, Prime Minister at the time, agreed to meet with a committee representing the missing persons.

This meeting resulted in the government drafting a bill to put an end to enforced disappearances, but in the most ironic turn of events, Human Rights minister Dr. Shireen Mazari claimed that the bill itself went missing after passing through to the senate.

The families of the disappeared are not alien to government representatives making empty promises. In 2021, politician Maryam Nawaz spoke loudly about Mudassar Naaru, a journalist who went missing in 2018. She met his son and wife and gave them assurances, but as soon as her party came into power, all promises were forgotten.

"After setting a dangerous precedent for enforced disappearances in the peripheries and using army propaganda to justify it to the civilian population, it is no surprise that intelligence agencies have acted with impunity and extended their reach to the rest of the country"

A history of neglect

The Baloch people have been the subject of economic and political exploitation at the hands of the ruling elite, while their demand for provincial autonomy has been neglected to serve the interests of the establishment.

Rather than granting them their reasonable demands and opening a dialogue with the Baloch community, the Pakistani state has chosen to label political dissenters and Baloch nationalists as ‘anti-state’ actors and ‘terrorists’, and proceeded to use every asset they have at their disposal to silence grassroots resistance movements.

Despite this, the Baloch people have continued to call for autonomy. And while some efforts have garnered results — such as the 30-day sit-in camp set up by the Baloch Students Council Islamabad demanding the safe recovery of QAU student Hafeez Baloch — many times the demand for justice falls on deaf ears.

“Baloch students have been protesting across the country for the safe recovery of Sohail Baloch, Fassieh Baloch, Feroz Baloch, Salim Baloch, Ikram Baloch, and several other students who were forcibly disappeared but to no avail,” Mazari said.

“In addition to these in-person protests, there are also regular social media campaigns on Twitter and Facebook that have been successful in bringing attention to various cases/stories of enforced disappearances.”

Mazari believes that despite the state feigning ignorance, these campaigns are significant in raising awareness and putting pressure, especially considering the mainstream media’s silence.

“If there was no impact of this, the military establishment through its present civilian facade would not be attempting (for the hundredth time) to penalise speech on social media through a proposed amendment to the Prevention Electronic Crimes Act,” she explained.

|

|

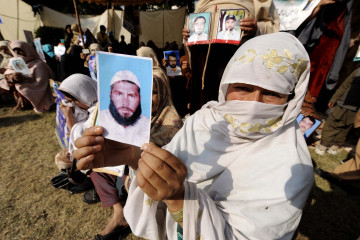

From the peripheries to the centre

After setting a dangerous precedent for enforced disappearances in the peripheries and using army propaganda to justify it to the civilian population, it is no surprise that intelligence agencies have acted with impunity and extended their reach to the rest of the country.

“Once reserved for nationalist and progressive activists in the peripheries, the practice is now being expanded into mainstream politics, with even relatives of political party members that have fallen out of favour with the establishment being subjected to abductions,” explained Ammar Rashid, an Awami Workers Party leader.

“Courts have also been rendered ineffective as a bulwark for ensuring habeas corpus,” he continued, noting that members of his own party have faced a similar fate.

“AWP members themselves (like Seengar Noonari, Shafqat Malik and others) have been abducted in the past. We believe it is an illegal and unconstitutional practice that should be criminalised and have called for a law against it that imposes penalties on abductors, as has already been done in other countries where this was occurring, like Mexico, Argentina and others).”

"The use of enforced disappearances to curb political freedom represents an attack on individuals and collective constitutional rights, and undermines the country’s already weakened democratic system"

The issue of enforced disappearances is not a stand-alone problem, but rather a reflection of the military establishment’s increasing control and influence in political matters requiring civilian and democratic solutions.

This military-civilian hybrid model, a term popularised after Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party formed a government in 2018, has been in play during most of Pakistan’s political history.

The use of enforced disappearances to curb political freedom represents an attack on individuals and collective constitutional rights, and undermines the country’s already weakened democratic system. The hybrid model has encouraged civilian governments to hide behind the military establishment.

Instead of engaging in political dialogue and fighting in the electoral ring, ruling parties have resorted to silencing journalists, disappearing political workers and opponents, and harassing and abducting dissenters and protestors.

“The looming threat of enforced disappearance is used to silence all forms of critique against the state. This is the main purpose of this practice: to stifle dissent,” Nida Kirmani, a professor at the Lahore University of Management Sciences, told The New Arab.

“The longer this continues, the worse the situation will become in terms of freedom of expression in Pakistan.”

Ifra Javed is a London School of Economics graduate, currently working as a researcher and lecturer at the Lahore School of Economics.

Follow her on Twitter: @Ifra_J

![Families and loved ones of missing persons continue to call for information and justice, but their calls have fallen on deaf ears. [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/large_16_9/public/455431489.jpeg?h=a13fdaa6&itok=dFORNiKz)

![More recently, enforced disappearances have become a widespread tactic used to silence dissenters and political opponents of the establishment. [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/large_16_9/public/1250092412.jpeg?h=58c8a5e7&itok=Q770AbLn)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News