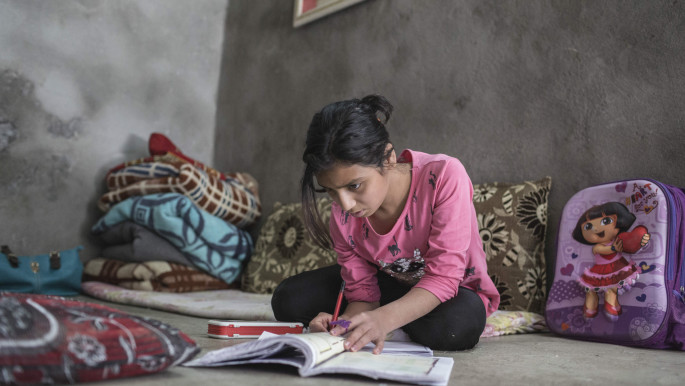

Rahaf lost both her parents and younger sister, along with ten other family members, when an airstrike hit their home in West Mosul in 2017. She was rescued from the rubble but is haunted by the memories, with everyday noises reminding her of bombs falling.

"The most important thing to me is that the war doesn't happen again. I don't want it to happen again. I don't want others to be orphans like me. I became an orphan. I hope nobody in Iraq gets orphaned," Rahaf says.

A year on, she still has shrapnel wounds in her leg. The experience of the airstrike, being trapped under the rubble and then learning of her family's death, left Rahaf unable to speak for weeks. She became withdrawn and isolated, afraid to go back to school and unwilling to make friends.

Rahaf is among scores of children in this city continuing to suffer a year after the Islamic State group's brutal rule was ended. The organisation seized Mosul in a lightning offensive across much of the country's Sunni Arab heartland, proclaiming a "caliphate" straddling Iraq and Syria in 2014.

Last December, the Iraqi government claimed victory over IS in Iraq, just months after Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi declared victory against the group in Mosul.

The experience of the airstrike and learning she had become an orphan, left Rahaf unable to speak for weeks. She became withdrawn and isolated, afraid to go back to school and unwilling to make friends

It was considered one of the biggest defeats for the Islamic State group, but the cost of this "liberation" has been immense.

Monitoring group Airwars estimated that between February and June last year, as many as 5,805 Iraqi civilians were killed in Iraqi and coalition attacks. But many believe the actual number is likely much higher, with rights group Amnesty International saying at the time that the "true death toll of the battle may never be known".

In addition to the deaths, nearly a million people fled their homes during the military operations and the fighting destroyed entire districts of the city, with the scale of destruction unprecedented in Iraq's most recent conflict. The UN estimated that the cost of repairing basic infrastructure is set to top more than $1 billion, with rebuilding likely to take several years.

However, one of the most catastrophic impacts of this battle has been the effect it has had on the mental wellbeing of civilians, especially children.

|

|

| Rahaf lost both her parents and younger sister in an airstrike last year [Sam Tarling/Save the Children] |

Haunted by fear

A year since the extremist group was expelled from Mosul, the city's children have been living in near-constant fear for their lives, often reliving memories of devastation, displacement, bombing and extreme violence, a new report by Save the Children has found.

Children have spoken of serious emotional problems, depression and extreme anxiety, with many bearing the scars of war.

Hundreds of thousands of children are still living amid the rubble, and many, including teenagers, say they are too scared to walk alone, be without their parents or go to school.

They have been pushed to breaking point, Save the Children found in their report entitled, Picking Up the Pieces: Rebuilding the lives of Mosul's children after years of conflict and violence.

"These are children who have spent their formative years under IS. They have seen their schools transformed into battlegrounds and their friends killed in classrooms," said Ana Locsin, Save the Children's Iraq director.

"School is no longer seen as a protective environment for children and it's hard for them to feel safe in the classroom, and therefore, to learn and thrive."

These are children who have spent their formative years under IS. They have seen their schools transformed into battlegrounds and their friends killed in classrooms

Twelve-year-old Fahad from West Mosul now attends a school with damaged walls and no doors.

"I don't feel good in the class," he says. "In this area, the sniper targeted the children so that when the mothers and fathers came to rescue them, he would shoot the whole family. The school got badly hit and the area became a front line. The whole street became a front line."

Another child, Dina adds: "At school, instead of teaching us maths, they used to teach us about missiles, bullets and slaughtering."

The 12-year-old orphan lives with her disabled aunt in West Mosul. She spoke of how IS fighters stopped and taunted her on the streets for not wearing a hijab. When she stood up to them, one of the militants cut her hair off as punishment. This scared her, she says.

Dina also saw her friend killed by Islamic State militants. They murdered her for "standing up to them", Dina says. "They shot her with a gun and she died."

She subsequently became withdrawn, depressed and isolated.

|

|

| Dina lives with her disabled aunt in West Mosul [Sam Tarling/Save the Children] |

Risks of long-lasting mental health issues

When aid workers first met Dina, her mental health was poor.

"She was isolated, had been out of school for three years and was exhausted from looking after her disabled aunt," reported Save the Children, which has been working in Iraq since 1991.

A caseworker provided Dina with psychosocial support, re-registered her in school and provided her with books, bags, stationery and a uniform.

Over time Dina's condition improved - she is now comfortable in the presence of strangers and is making friends again at school.

But poor mental health has become a recurrent theme among children here.

Almost half of the children surveyed felt grief all or a lot of the time, with fewer than one in ten children being able to think of something happy in their lives.

Save the Children also asked caregivers about social issues affecting the city's youth that might be on the rise in the community - 39 percent reported they knew of adolescents self-harming, while 29 percent said they had heard about adolescent suicide attempts increasing.

Parents also need support

To make matters worse, the report found the mental health of parents had been so badly affected by the conflict that children had been left with little family support, severely limiting their ability to break out of the devastating cycle of ongoing stress.

Instead of turning to overburdened parents and guardians, children are choosing not to speak about their problems, withdrawing from other people, and trying to self-soothe or accept their situation - and none of these are helping ease their emotional distress.

"Internalising issues could put children at further risk of poor self-esteem, isolation and suicidal behaviour, and exacerbate their symptoms of depression and anxiety," Ana said.

Internalising issues could put children at further risk of poor self-esteem, isolation and suicidal behaviour, and exacerbate their symptoms of depression and anxiety

Such is the case of Yasser, the father of three young girls. He lost his wife in February last year when an airstrike hit a grain store near his home in West Mosul. The burning debris flew through the roof of their home.

"With the last hit, all the blocks fell on us... My wife and I were sleeping," Yasser says.

"I told her, 'don't be afraid, don't be afraid, nothing has happened'. But she stayed that way, staring at me. She wouldn't respond, she kept staring at me, and she never got up," he recalls.

"At that moment, I didn't know what to do. I lost it."

The death of their mother affected his daughters deeply, and Yasser struggles as a single parent. Nine-year-old Rima, seven-year-old Aya and two-year-old Dalia now live with their maternal uncle and his family, as their father is unable to take care of them full time due to work.

Rima became depressed and angry after the loss of her mother and breaks down if anyone mentions her. The violence of the airstrike and the death of her mother affected Rima's ability to cope with intense feelings of sadness and emotional pain.

"Aya looks for her mum... she just wants her mum, she keeps saying 'mama'," says Yasser.

A Save the Children caseworker has been visiting the girls since their mother's death, providing psychosocial support and helping them to cope with their loss and regain their confidence.

"Unless children's sense of safety is re-established, and parents are given support to help themselves and their families, children will remain distressed, leaving them at serious risk of further and long-lasting mental health issues," Ana said.

Save the Children is calling on the international community to put the wellbeing of children at the heart of planning for post-conflict Iraq by stepping up funding for mental health and psychosocial programming and ensuring it is a key aspect of emergency responses.

"It is imperative that urgent action is taken to ensure children have access to essential services, can feel safe to walk around, play outside and go to school," Ana added.

"The future of Iraq depends on the development of its children into healthy, secure adults."

(Names in this article have been changed)

Sheeffah Shiraz is the Features Editor at The New Arab.

Follow her on Twitter: @SheeWrites

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News