Jordan's media and the battle for free speech

Arab journalists have been called on to become the latest recruits in the region's war against the Islamic State group.

Last week, media figures from across the region took part in an Arab League conference to see how they could assist their governments to curb the spread of extremist ideas.

The choice of Amman for the venue comes at a critical time for the country.

Bordering Syria, Jordan has been on the frontline in the battle against the Islamic State group, which threatens the stability of the relatively religiously diverse country.

Extremist ideas - particularly through Salafi-jihadi Jordanian ideologues such as Abu Mohammed al-Maqdisi - have grown in strength in some quarters over the past decade.

It is also estimated that there are 2,000 Jordanians fighting for IS.

Emirati political commentator Sultan al-Qassemi describes Jordan as one of the "most free" countries in the Middle East.

"The Middle East has witnessed a regression of freedom of speech since the Arab Spring erupted, with only Lebanon and Tunisia performing well," Qassemi said.

"That said, Kuwait, Jordan and Morocco still enjoy relatively higher degrees of freedom of speech compared to other states in the region."

Jordan is now at risk of facing further measures to gag the press. According to one survey, 95 percent of Jordanian journalists practice self-censorship.

However, with government traditionally keeping a close eye on the printing presses, it appears that there are new targets for the censors.

Online media outlets, usually run by young citizen journalists - dedicated to independent reporting and impartiality - feel most threatened by the latest censorship laws.

War on terror

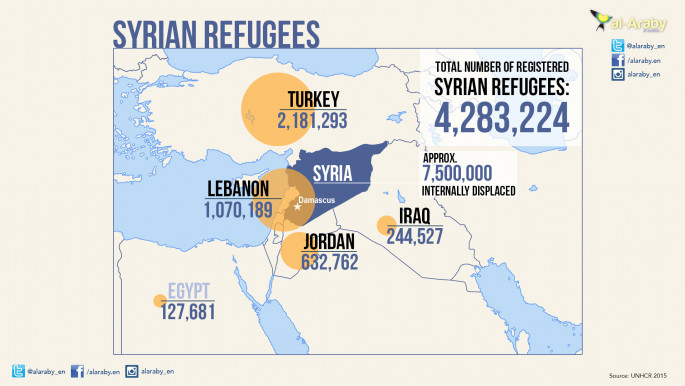

Syria's war has had a heavy impact on Jordan, which is hosting more than 600,000 Syrian refugees.

The country has become a leading member of the US-led anti-Islamic State group coalition, launching air raids against positions in Iraq and Syria.

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

When captured Jordanian pilot Muaz al-Kassasbeh was brutally murdered by the group - his death recorded by militants and widely shared on social media - Jordan's war on IS hit home hard.

It has made Amman a key ally of Gulf States due to traditional links and its stance against the terror group, the Syrian regime, and, to some extent, against Iran.

"Jordan has strengthened ties with Gulf States to unprecedented levels not seen since before the 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait," Qassemi added.

"This is due to a variety of economic, social and political reasons - however the impetus may have been the war on IS for which Jordan is the most vulnerable due its proximity to Iraq and Syria."

This presents something of a dilemma for Arab journalists.

Their pursuit for truth is at risk of becoming a victim of fear, as a contained Islamic State group looks at expanding its reach outside its "borders".

This is being pursued through violent sectarian attacks in the Gulf states, and the growth of IS affiliates in Libya, Egypt and Yemen.

IS has been successful in recruiting Jordanians to its cause through online media platforms - and many fear a "fifth column" could emerge.

Its team of savvy but ghoulish propagandists are viewed as one of the most technologically advanced and impactful in the region.

Jordan would be an obvious target for the group.

Although King Abdullah has successfully steered his country through the uncertainties of the Arab Spring, his earlier ideas for democratic reform have been put on hold.

Journalists face repressive new measures that threaten jail and other penalties if they diverge too far from government policy.

The latest measures includes press and publication, anti-terrorism and cybercrime laws, which critics say are used selectively to clamp down on critics of the government.

New media

The Arab League meeting has brought further fears that Jordan is about to embark on another set of draconian laws against free speech under the pretext of tackling terrorism.

"Their main objective seems to be an attempt to control the propagation of IS digital material. Many would consider that to be a noble pursuit in this age of religious extremism, where extremists thrive on shock value," said Naseem Tarawnah, founder of popular Jordanian blog Black Iris.

"We've seen how this plays out when governments attempt to 'regulate' this space. It manifests in laws that encourage censorship and fear, and have a tendency to extend beyond the perimeters of this content."

Tarawnah said that regulatory laws governing the media in the Arab world tend to be used for political purposes and to silence opposition.

However, it was the country's more orthodox penal code - not the more recent publication laws - which was used to prosecute Zaki Bani Irshied, deputy leader of Jordan’s Muslim Brotherhood.

Irshied was arrested in 2014 for criticising Jordan's Gulf ally - the UAE - on his Facebook page.

However, as his comments were made on social media he could not be charged with breaking press laws.

Writers and owners of blogs, websites and others news forums viewed as seditious can, however, be charged under the law.

As an unorthodox militant group, IS has relied on social media and video to spread its message and find its many willing recruits and sympathisers through online forums.

Tarawnah sees independent online media - particularly growing from the young - as the best way to tackle the proliferation of such ideas.

Government regulation of this "open market of ideas" could lead to a race to the bottom, however.

We saw this with the Syrian regime's handling of protests in 2011, and have come to learn that suppression only breeds further anger and violence.

However, Tarawnah said that stability is also a major concern of Jordanians, and the voice of the "man in the street" in rarely heard in mainstream media. The media has also been unsuccessful in convincing Jordanians of the importance of a free press.

"It's a war of ideas in a digital space. The goal should be to champion alternative narratives that can push back against forces we deem extremist," the blogger said.

"The way for one side to 'win' is to be a participant in that space, rather than shut out the competing voices, no matter how much one might find those voices to go against universal values of human rights."

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News