Jordan: A refuge through the ages

In the desert area of Azraq, where one of the four Syrian refugee camps are located in Jordan, many families, senior citizens and others unable to carry weapons and fight found a safe refuge almost 100 years ago, when the great Syrian revolution erupted in 1925, led by Sultan al-Atrash.

After the 1925 revolution, large numbers of Druze families went to Azraq because it is close to the Syrian border, which meant they could send food and supplies to the rebels when needed. Other Druze families settled in Amman, including Najib Gharz al-Din's father who was born in Salkhad, Syria. He moved between several areas of Amman during the 1920s, until he finally settled in the "Druze neighbourhood" in the Amman area of Jabal al-Joufa in 1962.

Najib said he had heard from the oldest Druze men in Azraq they had first gone to Saudi Arabia, which did not welcome them, so they went to Jordan instead. Historical sources show Jordanian forces stationed in Azraq were replaced with British forces to prevent any sympathy with the rebels, following pressure from Britain and France. There were also orders to stop anyone crossing the Jordanian-Syrian border from sunset to sunrise until the revolution was contained.

| After the 1925 revolution, large numbers of Druze families went to Azraq because it is close to the Syrian border. |

Although his family has been living in the Druze neighbourhood since the 1960s, when only six Druze families were there, Najib remembers they frequently went to Azraq to visit their relatives who had settled there. These relatives depended on salt marshes for their livelihood, despite the long distance and lack of paved roads. At the time, one return between al-Joufa and Azraq would take 16 hours.

Najib said only a few Druze families left Azraq, as most were granted Jordanian citizenship after living there for many years. This meant they could register their properties. As for Najib, he received citizenship after serving in the Jordanian army and earning a medal of honour for taking part on the Syrian front during the 1973 October War. When he was a child, he used to help his father grow wheat and malt - the profession of many Druze families at the time.

Najib, who considers himself Jordanian as he was born in the Amman area of Muhajirin, believes the biggest proof Jordan opened its doors to those seeking a safe refuge at that time is that this Druze community has comfortably remained in the same area for almost 100 years. "Why else would they stay even when they had the chance to return?" he wonders.

Manar al-Rashwani

|

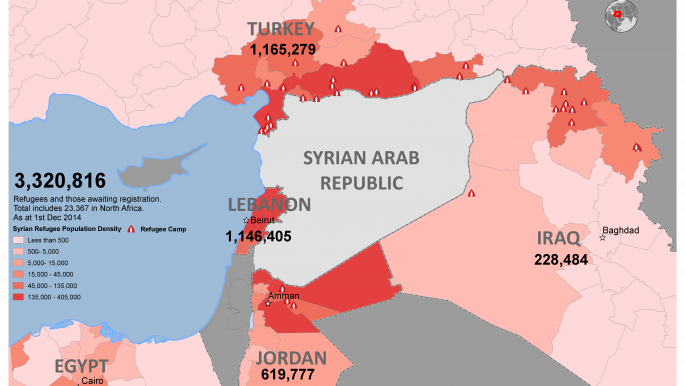

| Jordan plays host to over 600,00 Syrian refugees, but this is just the latest wave [UNHCR] |

Anyone entering the house of Syrian journalist Manar al-Rashwani in the Syrian city of Hama towards the end of 1982, would believe it was still inhabited. They would think the children were still in school, the father at work and the mother out visiting a neighbour. All the family took was one suitcase, leaving in a hurry and hoping they would return quickly.

They decided to leave on a July night during a black year for the city, as violent clashes left thousands of regime fighters and Muslim Brotherhood (MB) members dead. This was followed by indiscriminate arrests and the disappearance of many.

On that day the phone rang and was answered by eight-year-old Manar. He was the only one awake among his siblings, and his parents were out visiting friends. The "friendly" caller started asking about the children's uncle, who was known to belong to the Muslim Brotherhood. The children of Hama had been been trained to be security-conscious by their parents, and never give away any information to strangers. Manar did not answer the questions, and as soon as the call ended he called his parents and asking them to come back, pretending to be scared.

Fearing the mother being arrested instead of the uncle, as was the Syrian regime's policy at the time, the family decided to leave the city. They headed to Damascus where they stayed for a month, before crossing the border to Jordan where they lived with a relative in Bariha village in Irbid. This was Manar's first stop in Jordan, and it left him with unforgettable memories.

Manar estimates that the number of refugees in Jordan then was relatively small, and the prospering economic situation meant authorities were lenient towards the refugees. They were granted work permits and allowed to enrol in school. Manar was able to enrol in Moaz bin Jabal school in Bariha without showing any official papers to prove his grade, as they had left all their papers behind in Hama. The school simply took his mother's word for it.

Manar heard his parents talking about how the Jordanians had received refugees fleeing from Hama. They talked about how the people sympathised with them as they fled the brutal oppression of the Syrian regime, which accused Jordan of supporting the MB.

| Who in their right mind would buy furniture for a house they would only occupy for a few months before returning home? |

Due to the tensions between the two countries, Manar's father could not call his grandmother, whom he had not said goodbye to as they had left in a hurry. He did not get to reassure her he was alive. One phone call from Jordan to Syria would have been enough to destroy the entire family, as it would prove involvement. Months went by without any contact, and Manar's parents feared for the safety of family members who had stayed in Hama. The first phone call they could make to them was when Manar's father went to work in Saudi Arabia. It was safer to call from there.

The first of the many houses Manar's family stayed in in Jordan had minimum furniture and amenities. Who in their right mind would buy furniture for a house they would only occupy for a few months before returning home? This was 33 years ago, before the family moved to four other houses, and before journalists visiting Manar started getting confused when he said "us" or "here". Sometimes he would be referring to Syria, and at other times to Jordan, where he considers himself a citizen, even though he does not hold a Jordanian passport.

Elias Atallah

At the time of the Nakba in Palestine in 1948, ten-year-old Elias Atallah was at the German Johann Ludwig Schneller school in Jerusalem. That day he could not return to his parent's home in Haifa because the roads were blocked. Since then, Elias became a "disciple of Christ", as the school called him, and the name a group of 12 students at the school adopted when it became impossible to learn anything about their parents, even after the children's names were published in newspapers and read on the radio at the time.

The school took the "disciples of Christ" to Bethlehem and then to various parts of Lebanon. Elias was able to travel with the Jordanian passport his school obtained for him after proving his Arab descent and establishing he was a resident of Haifa before 15 May 1948.

Elias became a refugee for the first time after the Nakba. After the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, Elias became a refugee for a second time. He remembers the date very well: 11/11/1990. He took his blue SUV after the lives of his children and himself became endangered, and he drove to Jordan, which he chose as his new homeland as he had an old property in the capital Amman.

His trip ended in the Armenian district in Ashrafieh. There he lived in a small home. He was not new in the area; he had lived here in the late 1950s, when he worked at a Jordanian Armed Forces blanket factory in Zarqa and then at the Jordanian petroleum refinery built the same decade.

Amman had changed much between his two visits. Ever since he had arrived in the city, he had seen multiple waves of Iraqi and Syrian refugees come, many of whom became his neighbours. He knows many of their stories by heart.

Elias does not hide his regret at having returned to Jordan. But he is proud to have been part of one achievement in the city, the construction of the Jordanian petroleum refinery. He still has his uniform from those days, bearing the logo of the Italian contractor Snamprogetti, which he took with him to Kuwait in 1960 and brought back to Amman in 1990.

Salma

The night in 2003 when Baghdad fell was very harsh for Salma's family. That night, her family could not sleep at their temporary home in Amman. She was glued to the tv for days, trying to understand what was happening.

Salma says it did not matter that Saddam's regime was responsible for driving her out of Iraq, because the way he was toppled was humiliating for the Iraqis as she stressed. When the family learned that the husband was named in an Iraqi Agriculture Ministry investigation in 2000, they decided to flee immediately. Back then, it mattered little whether a person was innocent or guilty, as nothing guaranteed a their safety either way.

The first stop was Amman, where the husband's family had been living since the 1990s. The family owned factories producing goods for export to Iraq during the embargo.

The family did not buy a house in Amman during that period. They even refused an offer to buy an apartment at a cheap price from the landlord, who practically begged them to buy it. Their logic was: what is the point if they were going to return after the danger passes?

They even returned temporarily to Iraq and took some of their belongings to prepare for their permanent return after the ouster of Saddam's regime. But they did not stay for more than a few months, and they returned to Amman because of the lack of security. Years later, they took in another temporary refugee in their home.

Fadia, Salma's sister, arrived in Amman in July 2011. She was still recovering from a bullet that had hit her jaw on the same day she saw her husband die in front of her while travelling in a government car issued to forensic doctors. The car had distinct markings that made it easy for the killer to identify her husband.

When she was interviewed, Fadia was preparing to return to Australia where she had been given permission to resettle with her 11 year old son. She had spent two years in Amman waiting for her application to be approved. She could barely afford to live in the city, one of the most expensive capitals in the region if not the world.

There are many reasons why Salma and Fadia's family fled to Amman, settling in its quarters where Iraqi refugees are concentrated. The first wave came for purely economic reasons, the second because of threats to the life of the breadwinner, and the third came because of actual loss of life.

Sana/Syrian revolution 2011

Sana identifies herself as the "last" to leave Yarmouk refugee camp in Syria, having borne witness to the devastation there. Her family had refused to abandon their home until there was no other option left.

| It was not easy for a displaced Syrian woman without no source of income to escape from the harassment. |

Her husband went to Jordan, hoping to find shelter for his family. Sana was left alone in Damascus, moving between the homes of relatives and charitable folk who offered their homes to those who had lost theirs because of events following the start of the Syrian revolution in 2011.

Sana and her daughters did not remain in these homes for too long. It was not easy for a displaced Syrian woman without no source of income to escape from the harassment that women are usually subjected to in difficult times, as she said. She decided to join her husband in Jordan even before he could find a job or appropriate shelter, and despite the fact that he had cautioned her that the family would fare no better in Jordan, even though there was no fighting there.

Without being fully aware of the difficulty of the journey ahead, she packed her bags and took her children along with another family. They chartered a bus the cost of which they split.

The most difficult leg of the trip was when they had to travel through abandoned buildings, dodging the bandits infesting the roads. The bus headed to the border between Syria and Jordan, to the Jaber official border crossing. Once there, she realised it would take almost a month to cross legally.

Based on advice from her peers, she went to the Nassib crossing where she was told it would be easier to cross the border into the Zaatari camp. However, the situation there was even worse. Many women, children, and elderly people had been stuck there for weeks waiting to be allowed in, their passage being coordinated between the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and the Jordanian army.

Her turn may have come quicker if she had caved into blackmail and harassment by powerful individuals in the area. Instead, she stood in the street crying bitterly and looking for anyway to return to war-torn Damascus instead of the humiliation and harassment at the border.

But rather than returning Damascus, she ended up in Zaatari camp. Sana met two FSA members there who told her the revolution was meaningless if it could not stop harassment against Syrian women fleeing the violence, and they took her to the Jordanian gendarmerie in a private car.

The last stop was Amman, after a short sojourn in Zaatari. She obtained permission from Jordanian security to visit her husband in Amman, after she found herself at the office of a security officer trying to justify a failed escape attempt by a group of Syrians from the camp.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News