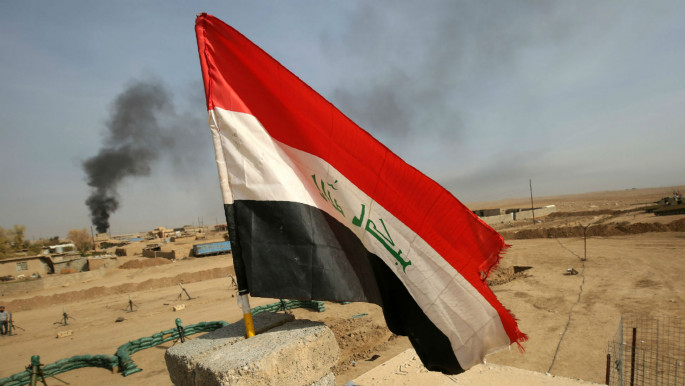

The Iraq Report: Iran's economic woes frustrate Shia militias

Pro-Iran Shia militias in Iraq are beginning to feel a squeeze on their finances as their benefactor's economy is ravaged by American sanctions and one of the worst coronavirus infection rates in the Middle East.

Without an effective bridge between the disparate Shia factions in Iraq and a key player within Iran, as represented by the late Qassem Soleimani who was killed earlier this year, Shia militants are beginning to show signs of discontent.

But the militias are far from separated from their backers in Tehran. Attacks against American forces deployed to Iraq have come as Baghdad and Washington engage in their first strategic dialogue in more than a decade to decide the future shape of relations between the two countries.

While it is clear the US leadership want to draw down their military presence, they would be loathe to do so in a manner that makes it appear the Iranians and their proxies were the ones to force them out.

Iran's economic woes frustrate Iraqi Shia militias

Six months on, the Iranians and their Iraqi proxies are still reeling from the dual loss of Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force commander, Qassem Soleimani, and Iran's "man in Iraq", Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, both of whom were killed by a US drone strike in January.

|

Pro-Iran Shia militias in Iraq are beginning to feel a squeeze on their finances |  |

According to recent reports, on his first visit to Iraq in April, Soleimani's successor Esmail Ghaani visited a gathering of Iran's top proxies in the country. Unlike Soleimani, however, Ghaani did not offer the militants cash and largesse, but instead gave each commander a silver ring – a symbolic gesture in Shia Islam.

However, sources have indicated that the silver gestures of brotherhood failed to impress the militia leaders who wanted the cash that Soleimani had gotten them accustomed to for the better part of two decades.

Rather than engender loyalty and bonds of brotherhood based on their decades of cooperation and their shared religious affiliation, the Shia militants are instead now concerned that Iran may be losing its ability to lavish funds on its most effective proxies outside of Lebanon's Hezbollah.

|

|

| Read more: The Iraq Report: Energy politics cripple hopes for economic recovery |

This was exacerbated by Ghaani informing them that "for the moment" they would have to rely on Iraqi state funds to keep themselves financed.

Iraq's budget for the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF) – an umbrella organisation of predominantly pro-Iran Shia militants that is formally a part of the Iraqi armed forces – stands at $2 billion of the national budget. However, as the PMF is essentially a patchwork of different Shia Islamist factions, the bigger armed groups get more of that budget than smaller outfits.

They are therefore increasingly reliant on alternative sources of revenue, including controlling city checkpoints up and down the country where "tolls" are paid by citizens, as well as cash handouts worth millions from the Iranians.

The reaction to Ghaani's gestures and his speech could not have been more pronounced. Rather than simply saunter through Iraq's borders as Soleimani had once done, Ghaani needed to apply for a visa before visiting the country earlier this month.

During his visit, Ghaani met with the Iraqi Popular Mobilisation Forces' (PMF) de facto leader Abdulaziz al-Mohammedawi, better known by his nom de guerre Abu Fadak. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that Ghaani will not be able to bring together the various leaders of the PMF, an umbrella Shia militant organisation.

|

Iraq's budget for the Popular Mobilisation Forces stands at $2 billion |  |

While Iran's Iraqi allies may meet with him, Ghaani lacks the charisma, charm, and Arabic language skills of Soleimani. Until his last moments, Soleimani was seen as approachable and open-handed in his largesse towards his Iraqi proxies.

Ghaani, on the other hand, appears to be gaining a reputation for miserliness, and his communication through an interpreter is doing little to ingratiate him with the men he is supposed to command.

Soleimani combined material incentives with religious discourse but keenly understood that, ultimately, it was money and not a shared religious identity that would keep Iran's proxies happy and working to further Tehran's aims in Iraq and beyond.

|

|

| Read more: The Iraq Report: Pro-Iran MPs demand Saudi 'reparations' for suicide bombers |

Ghaani's overreliance on past loyalty to Iran as well as religious gestures will face significant hurdles and will expose the limitations of Iraq's modern Shia Islamist political ideology and discourse as splinters form and conflicts spread over which factions get the largest proportion of the budget.

US-Iraq strategic dialogue gets underway

The first US-Iraqi strategic dialogue got underway on Thursday for the first time in more than a decade in a bid for Washington and Baghdad to shore up their differences and create a new understanding on which to base their future relations.

However, and due to a succession of weak Iraqi governments and now the coronavirus pandemic, the discussions have been demoted to an online dialogue between the senior officials of both states raising concerns that there will be few breakthroughs in bilateral ties.

"The entire US-Iraq bilateral relationship will not be fixed in a single day," said Robert Ford, an analyst at the Middle East Institute and a US diplomat in Baghdad during the last round of strategic talks in 2008, which ironed out the US drawdown from the occupation that began after the 2003 invasion to topple Saddam Hussein.

|

Stuck in the middle of the US and Iran's war of influence are normal Iraqis who have not had a functioning government since 2003 |  |

"But for once, we seem to have the right people in the right place at the right time," he said. Bilateral ties had been at their coldest in years, Iraqi and US officials said, following deadly rocket attacks on American military and diplomatic sites since last year.

Tensions then skyrocketed following the US drone strike near Baghdad Airport in January that killed Iranian commander Qassem Soleimani and Iraqi militant chief Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, prompting Iraqi lawmakers to vote in favour of ousting all foreign troops.

In response, Washington threatened crippling sanctions and, according to US military sources, began planning a vast bombing spree against groups blamed for the rockets. However, tensions have since eased since Mustafa al-Kadhimi became prime minister last month. The former Iraqi spy chief and journalist had courted US officials during his time as head of intelligence in the war against Islamic State extremists.

|

|

| Read more: How Iran's Quds Day propaganda pictures backfired |

This has led the White House to feel comfortable with Kadhimi in a way they never were with his predecessor Adel Abdul Mahdi who had to stand down after protests ripped through Iraq and security forces and allied militias brutally suppressed demonstrators, killing hundreds.

Washington's ease with Kadhimi could be reflected in the American decision to continue a winding down of US troops in the country. However, the Americans are unlikely to simply get up and go, as pro-Iran groups have continued to attack US forces in Iraq.

Hours after missiles slammed into a base used by US forces wounding four American soldiers on Tuesday, prominent Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr urged Washington to withdraw from Iraq entirely, describing them as "occupying forces" despite their presence being at the invitation of the federal government.

Should President Donald Trump order a departure from Iraq on these terms and in these conditions, it would be viewed as an American defeat. Considering the domestic racial turmoil currently afflicting the United States in the wake of the killing of George Floyd and in the run up to an election this year, it is extremely unlikely that Trump would be willing to show weakness by departing from Iraq.

Further, the Trump administration believes that its "maximum pressure" campaign against Iran is yielding results and, with the cracks forming between the various PMF factions in light of Tehran's domestic and economic troubles, the White House may feel vindicated in adopting this approach.

The US may also consider that by boosting support to Kadhimi and staying put they may begin to undermine Iran's proxies and begin to loosen Tehran's grip over Iraqi policy.

However, stuck in the middle of the US and Iran's war of influence are normal Iraqis who have not had a functioning government since 2003. Replacing the grip of the Iranians with that of the Americans may not seem an attractive prospect to many who simply want Iraq to chart its own path forward without the meddling of foreign powers.

The Iraq Report is a fortnightly feature at The New Arab.

Click below to see the full archive.

|

|

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News