Iraq: Disparate forces converge for grand Mosul battle

An unlikely array of forces is converging on the city of Mosul, lining up for a battle on the historic plains of northern Iraq that is likely to be decisive in the war against the Islamic State group.

The tacit alliance — Iraqi troops alongside Shia militiamen, Sunni Arab tribesmen, Kurdish fighters and US special forces — underscores the importance of this battle. Retaking Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, would effectively break the back of the militant group, ending their self-declared caliphate, at least in Iraq.

But victory doesn’t mean an end to the conflict. In a post-Islamic State Iraq, the enmities and rivalries among the players in the anti-IS coalition could easily erupt.

The battle, expected near the end of the year, threatens to be long and grueling. If IS fighters dig in against an assault, they have hundreds of thousands of residents in the city as potential human shields. And as residents flee, they fuel the humanitarian crisis in Iraq’s Kurdish region around Mosul, where camps are already overcrowded with more than 1.6 million people displaced over the past two years. Humanitarian groups are rushing to prepare for potentially 1 million more who could be displaced by a Mosul assault.

The biggest prize captured by the militants after they overran much of northern, western and central Iraq in the summer of 2014, Mosul has been vital for the Islamic State group. The reserves in its banks provided a massive cash boost to the group, and the city’s infrastructure and resources helped IS as it set up its caliphate across Iraq and Syria.

Mosul was the location chosen by Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi to make his first public appearance after declaring the caliphate, a triumphant sermon delivered at a historic mosque in the old city. For the past two years, much of the leadership seems to have operated from Mosul.

If Mosul is retaken, it would be a nearly complete reversal of the jihadis’ 2014 sweep. The group would be left with only a few pockets of territory in Iraq. IS fighters have already responded to battlefield losses by reverting to guerrilla-style tactics or retreating into neighbouring Syria to defend the group’s territory there, which is also rapidly eroding.

|

Iraq’s military is thousands of soldiers short of the estimated 30,000 troops needed to launch the assault |  |

|

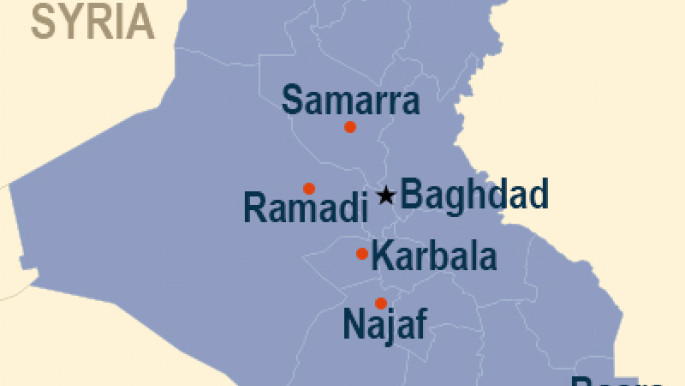

For weeks, the disparate forces have clawed back territory in Nineveh province, where Mosul is located, seizing villages and key supply lines. Still, the Iraqi military’s closest position is some 30 miles south of Mosul and there remain dozens of militant-held villages with civilian populations that the troops must take before reaching the city’s outskirts. Kurdish forces are closer, some within 10 miles of the city to the north and east.

US-led coalition forces have sped up training for Iraqi troops and Kurdish fighters, condensing courses that once took more than two months into just four weeks. In July, the Pentagon announced that 560 more US troops would deploy to Iraq to transform Qayara air base, south of Mosul, into a staging hub for the final assault.

Still, Iraq’s military is thousands of soldiers short of the estimated 30,000 troops needed to launch the assault, and the existing forces are stretched thin trying to hold other recaptured territory, particularly in western Anbar province.

Iraq’s “biggest challenge is generating the forces required to get to Mosul,” said Maj. Gen. Gary Volesky, the head of US ground forces in Iraq. “If you want to pull someone out of Anbar to go to Mosul, you’ve got to put somebody else there.”

Iraq’s military fell apart when it fled Mosul in the face of the IS blitz two years ago, with a third of its troops melting away. In the ensuing months, it was revealed that tens of thousands of troops on the rolls did not exist: They were only names whose pay was pocketed by commanders. Since then, the military has been slowly rebuilding, while other armed forces such as Shia militias and Iraq’s Kurdish forces have steadily grown in strength.

The rivalries within the alliance are already starting to show and are likely to come to a head once IS falls.

The Kurds, who seized large swaths of territory during the fight against the militants, want to keep them. Iranian-backed Shia militias demand recognition for the political and military strength they have garnered during the war. The Sunni minority is deeply worried about Shia domination and discrimination, and those fears are likely only to grow as the community tries to recover from Islamic State rule and return to their homes.

|

Victory doesn’t mean an end to the conflict. In a post-Islamic State Iraq, the enmities and rivalries among the players in the anti-IS coalition could easily erupt |  |

The Shia-led government in Baghdad will have to balance among these factions.

The most immediate question will be whether Shia militias and Kurdish forces will join the assault into mainly Sunni Arab Mosul. It’s a sensitive issue. Shia militias have been accused of abuses against Sunnis in other areas they have retaken from the Islamic State group. If Kurds capture parts of the city, it gives them a strong card in future negotiations over the territory they hold.

Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has said all forces will participate in the Mosul operation, a nod to Kurdish and Shia militia demands.

But at a news conference last week, he also said Iraqi military decisions must respect the delicate ethnic balance in Nineveh province, where most of the population is Sunni Arab, with pockets of Kurds, Shias, Christians, Yazidis and other minority groups.

When asked what role Shia militias would have in Mosul, al-Abadi was circumspect. “I don’t want Daesh to make use of sectarian conflicts,” he said, using the Arabic acronym for the Islamic State group.

Sunnis make up the vast majority of the 3.3 million Iraqis displaced by the conflict. The treatment of civilians in Mosul will likely be seen as a test of the government’s commitment to lasting political reconciliation. The marginalization of Sunnis and increasingly sectarian politics under al-Abadi’s predecessor, Nouri al-Maliki, fueled the rise of the Islamic State group in Iraq to begin with.

For al-Abadi, retaking Mosul is a key political prize. In office just over two years, he has faced increasing anti-government sentiment fueled by IS attacks in and around the capital and the failure to fight corruption or bring reconciliation.

Al-Abadi said he believes Iraq is more unified today than when he took office, but difficulties still remain and “new challenges” are likely to erupt after Mosul is liberated.

“Some people tell me we should delay the liberation of Mosul because of these challenges,” he said. “I say: No.”

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News