The failed reconstruction of Lebanon's Nahr al-Bared Palestinian camp

Today, as more violent conflicts rage in Syria and other areas of the Middle East, this war is largely forgotten by the international community.

But for the thousands of Palestinians still displaced, living in metal containers waiting for their homes to be rebuilt, the impact of that war is as present as ever.

The horrific scale of destruction in 2007 moved both the United Nations and the Lebanese government to agree to rebuild the camp.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, (UNRWA), took on the role of regulating the reconstruction of the camp.

Following the promise of international funding from a donor conference in Vienna, UNRWA planned reconstruction to be complete by 2011. Today, 12 years later, only 54 percent of the camp has been rebuilt.

|

|

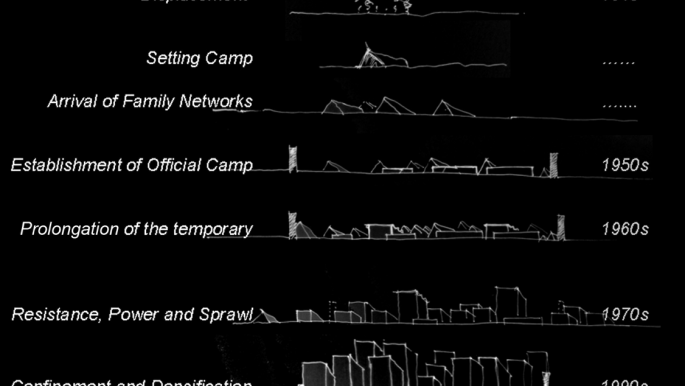

| Levels of urban development in Nahr al-Bared 1948-2007 [UNWRA] |

The camp was once home to over 27,000 Palestinian refugees. The first generations had been displaced from Palestine in 1948 and 1967.

"Because of the position of the camp, we soon became the wealthiest amongst the Palestinian communities in Lebanon," explains Issa El Sayed representative of the Palestinian Popular Committee in Nahr al-Bared.

Halfway between Tripoli and Homs, Nahr al-Bared was one of the main economic hubs of northern Lebanon, home to a large souk, a must-stop for most commerce running between Lebanon and Syria.

The camp was completely destroyed in 2007 during five intense months of battle, sparked by retaliation violence between the insurgent al-Qaeda inspired group Fatah al-Islam, and the Lebanese army.

By the end of the clashes, only five percent of the original buildings and infrastructure had survived the siege and bombardment of the Lebanese Armed Forces.

The repeated shelling of the camp led to the killing and capture of most militants, as well as the forced displacement of the whole Palestinian population from the camp.

|

|

| Nahr al-Bared refugee camp in 1948 [UNWRA] |

Rebuilding: A trial ground

In an unprecedented move, the Lebanese government agreed to rebuild the camp.

"This had never happened before in Lebanon," continues El Sayed, speaking to The New Arab from the Popular Committee's headquarters located inside the camp.

"No other Palestinian camp destroyed during the Lebanese Civil war (1975-1990) has ever been rebuilt," he says remembering the destruction of other Palestinian camps like Tel al-Zaatar by right-wing Lebanese militias in 1976.

"They want to turn Nahr al-Bared into an example of how to regulate and better rule over Palestinians in Lebanon. Nahr al-Bared is their trial ground," he concludes.

Palestinians in Lebanon are not allowed citizenship rights. They cannot own property, and are excluded from practicing more than 72 professions.

Education and medical assistance are managed by UNWRA, and most camps despite internally secured by armed Palestinian factions, remained surrounded by Lebanese Army checkpoints.

|

Palestinians in Lebanon are not allowed citizenship rights. They cannot own property, and are excluded from practicing more than 72 professions |  |

"There are many reasons reconstruction took longer than expected," explains John Whyte, project manager of UNWRA's reconstruction of Nahr al-Bared.

"It took nearly two years just to clear the rubble and unexploded ornaments in the camp. Over 12,000 unexploded ornaments had to be removed, it was probably the most contaminated site in the world at that time."

|

|

| The destruction of Nahr al-Bared in 2007 [UNWRA] |

"It took time to negotiate with all the different department stakeholders in the Lebanese government," continued Whyte.

"We had to follow security measures dictated by the Lebanese Armed Forces and the Department of Antiquities, when they discovered extensive archaeological remains located under the site."

Critiques of reconstruction and allegations of corruption

But according to many Palestinian residents of the camp, it is more than just complicated logistics slowing down the rebuilding process.

"The destruction of Nahr al-Bared was planned much before the beginning of the conflict with Fatah al-Islam," says Khaled M., a resident in Nahr al-Bared since his parents left Gaza in 1952.

Working as a local aid worker for an international NGO when the war broke out, Khaled witnessed aid cargoes arriving weeks before the start of the siege.

"I had family in Beddawi, the nearby Palestinian camp in Tripoli. I remember them telling me that extra mattresses and food provisions were being distributed in schools all over the camp, apparently for no known reason."

|

Nahr al-Bared was purposely destroyed to have an excuse to re-build it differently, securitised and transformed into a model for other permanent Palestinian camps in Lebanon to follow |  |

Many in Nahr al-Bared are keen to believe close variants of Khaled's story, convinced that Nahr al-Bared was purposely destroyed to have an excuse to re-build it differently, securitised and transformed into a model for other permanent Palestinian camps in Lebanon to follow.

"It's a form of imposed control," Khaled tells The New Arab. "They have rebuilt houses smaller than before to allow for larger roads. Buildings cannot be higher than four floors, and have no basements, to avoid tunnels being dug up."

UNWRA rebuilds the buildings using Lebanese companies employing Palestinian workers. But the land and the buildings remain property of the Lebanese government.

Nonetheless, walking through the reconstructed areas of the camp, it is obvious that with the right amount of influence, certain rules can be bent.

Many are the cases of Palestinian families owning buildings through informal contracts with Lebanese landlords, themselves in agreement with government officials to build higher buildings, and modify the structure of UNWRA constructions.

Faez I., a young resident of Nahr al-Bared, still lives with his family in a small iron container.

"It is all about politics and power," he tells The New Arab. Having owned a large house before the war, Faez's family have refused to move to one of the two-bedroom flatlets built by UNWRA, complaining that their former house was at least double the size of the new one, and that their 10-member family would not fit in the new accommodation.

"If I go to John Whyte to understand why this house is so much smaller than my old house, he can just say, 'show me evidence that you even lived in this house'. And of course, I do not have the papers, nobody has evidence."

When asked to comment on the matter, Whyte seems very aware of the discontent amongst Nahr al-Bared's Palestinian residents.

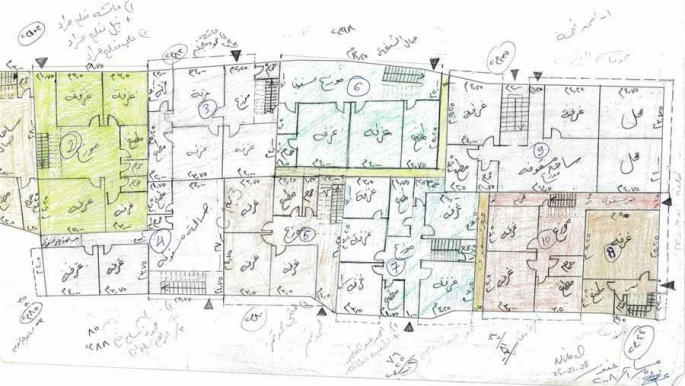

"We have tried to involve the community every step of the way," he explains while showing us the hand-drawn diagrams of a survey run in 2007 by local activists of Nahr al-Bared Reconstruction Commission in collaboration with UNRWA.

"There were no maps before the war, nothing – it was all built on people's memories through a comprehensive project of community mapping."

|

|

|

|

| Community work in the house-to-house recollection of families prior to the 2007 war [UNWRA] |

"My job is to see through the planning and reconstruction. After a one-year liability period, we give the keys to the families and have no obligation over what they do with the apartment".

He continues, "The long-term issue of governance of the camp is for the Lebanese government to handle not UNRWA."

Twelve years on, UNRWA still needs funds to complete the rebuilding.

"One of the problems is that the international community no longer view the situation as an emergency 12 years on. But for those still living in temporary accommodation, the situation still very much is an emergency," Whyte explains.

This is the first rebuilding project UNRWA has ever undertaken on such a large scale. And its sheer cost raises the question of the contradiction inherent in rebuilding a refugee camp, a place that should be temporary by definition.

Considering that both UNRWA and the Lebanese government formally respect the right of return of Palestinians to Palestine, Whyte acknowledges the inherent contradiction of rebuilding a refugee camp "with the logic of this being a long-lasting place".

"We are Palestinians and want to return to our country" concludes Khaled. "But we also have a right to a dignified life in Lebanon, with fully recognised citizenship rights, including a decent living situation in Nahr al-Bared and in all other Palestinian camps of the country."

One of the most educated young populations in the region, also thanks to UNWRA's educational support, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon could be a vital contribution to the bettering of Lebanon's impoverished economy. If only there was the political long-sightedness to realise.

Roshan De Stone is a human rights advocate working in Syrian refugee camps in Lebanon. She is a full-time contributor to Brush&Bow.

David L. Suber is a political researcher and journalist. He is directing a documentary on deportations from Europe and currently lives in Lebanon, where he works in refugee camps. David is a full-time contributor to Brush&Bow.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News