Eighteen years after 9/11, what's going on in Guantanamo?

Family members of the victims and survivors of the attacks file into the gallery at the back, where they can watch proceedings through the glass. Eighteen years after the event, this is the 34th pre-trial hearing for "the 9/11 five" since they were charged with war crimes in 2012.

After one failed attempt under Bush to try them, and a second under Obama to transfer the trial to federal court, it was decided the death penalty case would be tried at the Military Commissions "war court" in Guantanamo Bay.

But what's often referred to as the biggest criminal trial in US history has met with a host of obstacles, some logistical, others stemming from the central issue of the torture the detainees endured while held at now-infamous CIA black sites. Much of the information sought by defence legal teams is classified for reasons of national security - but the US government still hasn't provided a clear guide to exactly what is and isn't classified.

In addition, questions of government intrusion in defence activity have dogged the case, and two of the five defence teams are currently boycotting proceedings until they can be properly resolved.

A few minutes later, the guards stand in formation, and the second alleged co-conspirator is brought in. He is Walid bin Attash, accused of running an al Al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan that trained two of the hijackers. In a beige combat vest, he sits at the second bench, chatting to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) and to his lawyers.

Read more: Secret tapes of alleged 9/11 plotters at centre of Guantanamo war crimes hearing

The courtroom continues to fill up with paralegals, court interpreters, defence teams, guards and the prosecution. Ramzy bin al-Shibh, a Yemeni detainee, arrives next, wearing a long, thin kuffiyeh-patterned scarf bearing the Dome of the Rock that he drapes on a screen in front of him.

At a Commission hearing in 2015, Mr al-Shibh stated in court he could no longer trust his interpreter because he recognised him from a CIA black site. The interpreter denied any association with the CIA, but the government later confirmed it, stating his presence on the defence team was not - as suggested by defence lawyers - due to a government effort to gather information about defence team activities, rather a failure of defence team vetting.

|

|

| The five defendants in the 9/11 case sit in court at a pre-trial hearing with their interpreters and defence teams [Janet Hamlin] |

Following shortly behind him is KSM's nephew, Ammar al-Baluchi, accused of organising the travel and finances of at least 13 of the hijackers. Younger and sturdier, he wears a long black shirt and orange-tinted glasses to help prevent migraines. He hangs his prayer mat on the back of his chair, sits down next to his defence team, and takes out a malleable blue stress ball to squeeze.

Last to take his seat at the end of the fifth bench is Mustafa al-Hawsawi. The 2014 Senate "Torture Report" on the CIA's black sites programme states he was diagnosed with chronic haemorrhoids, an anal fissure and symptomatic rectal prolapse after being subjected to "rectal rehydration and feeding" while in CIA custody, described by his lawyers as "sodomy". Two years ago he underwent reconstructive surgery at the base, and sits on a cushion and pillows in court.

After the obligatory first session, Mr al-Hawsawi usually waives his presence.

|

Mr Hawsawi's lawyer operates under the assumption that it's impossible to ensure communications are watertight |  |

The issue of monitoring and interference in defence activities is first on the docket. In 2013, Mr bin Attash's defence lawyer noticed a listening device - which the prison guard said was a smoke detector - in the room she was using for privileged client meetings at Camp Echo. The prison commander later acknowledged the capacity for monitoring existed, but said their meetings were not under surveillance.

Military Judge Colonel James L. Pohl - who is no longer on the case - ordered that monitoring should be banned, and after a long series of motions, the defence says it is now satisfied with the recent sweep. Brigadier General Mark Martins, speaking for the prosecution on the Monday of the hearing, assured the defence of "reasonable efforts to ensure that [your] communications are confidential".

Walter Ruiz, Mr Hawsawi's lawyer, however, operates under the assumption that it's impossible to ensure communications are watertight. "We're always wary and cautious about what we say, and where we say it," he says.

This isn't the first time concerns about government interference have come up. As recently as January, a former defence team paralegal was questioned first by military intelligence, then by the FBI, about the defence team and their work. Until more is known about the FBI's investigation, KSM and Mr bin Attash's teams are boycotting proceedings.

|

|

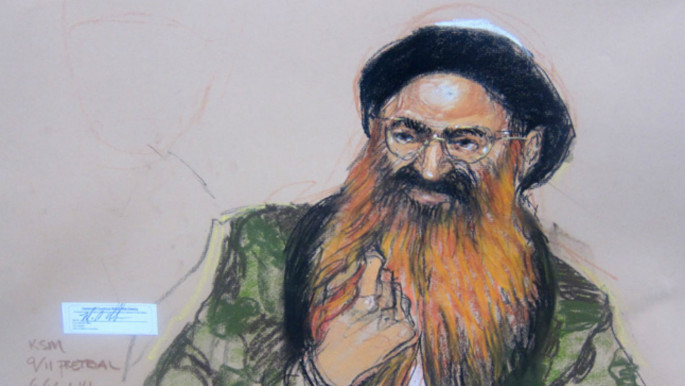

| Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged 9/11 ringleader, was captured in 2003, and transferred to Guantanamo Bay in 2006 [Janet Hamlin] |

In the courtroom, too, at least two incidents have raised suspicions of third-party monitoring.

Separating the media, NGO observers and victim family members from the courtroom is a triple-glazed window. The audio-visual feed arrives on screens with a 40-second delay, intended to allow the judge or court security officer to interrupt access in the event classified information is leaked in court.

But in 2013, the red beacon on the judge's desk began flashing, and white noise interrupted the feed. It soon became clear that an outside censor had hit the "kill switch", much to the judge's dismay; he did not know anyone else was monitoring the feed.

Questions of transparency and access trace a common thread through the week. In parallel to these "open" sessions that take place during hearings, closed sessions are scheduled too, allowing for discussion of classified information. Military Judge Pohl had ruled in favour of hearing testimony from the interpreter - who Mr bin al-Shibh had recognised in court - in a closed session. But, this would, it was argued in a brief by 12 news organisations, set a "deeply disturbing precedent".

|

The government has declined to reveal exactly how they obtained the recordings and a gag order prevents Mr Connell from asking further questions |  |

At the eleventh hour, on Wednesday night, a higher court temporarily blocked the closed testimony, postponing a decision on it, in a "rare win" for the defence.

Explaining to the court on Monday how a lack of access to information had impacted his team, Mr al-Baluchi's lawyer, James Connell, revealed the existence of phone calls - allegedly between four of the accused plotting 9/11 - that were intercepted by the US government, but only handed to the defence in 2016.

The government has declined to reveal exactly how they obtained the recordings and a gag order prevents Mr Connell from asking further questions.

|

|

| Military Commissions are held at Camp Justice, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba [Katy Stone/TNA, photo approved by DoD] |

This is important because the sources and methods of the surveillance used could, Mr Connell argues, reveal information about whether the government considered itself at war with Al Qaeda prior to 9/11.

When exactly the war began might seem either to be basic or irrelevant. But resolving the issue of the status of hostilities is fundamental to the trial's progress - if it transpires the government did not consider itself at war when 9/11 happened, the men cannot be tried at the Commission for war crimes, says Mr Connell.

Mr Hawsawi has had the chance to argue this point, but Mr al-Baluchi's team are now seeking the same opportunity.

"Everybody should get their own day in court," he says. The prosecution states that what was ruled for Mr Hawsawi must apply to all five men, and that 9/11 constituted an act of war in and of itself.

Another core question yet to be resolved is the use of statements taken by the FBI soon after the men arrived in Guantanamo. The previous judge had ruled them out, and the defence says the three years of torture the defendants endured in the black sites had programmed them to confess. Whether Marine Judge Colonel Keith Parella chooses to overturn this decision is key, but he is due to begin a new role in the summer, just a year after arriving on the job.

"It's difficult to litigate at Guantanamo. And I don't mean for us on the defence. It's difficult to have a functioning alternative judicial system on a remote base, with ad hoc logistical arrangements." says Mr Connell. After just a day and a half of open court, the hearing closes until the next session at the end of April.

A trial date is yet to be set, and for the survivors and victim family members who made the trip to the remote island base, it's unclear when, or even if, that day will come.

Editor's note: The prosecution did not respond to our request for comment.

Katy Stone travelled to Guantanamo Bay to cover the 25-29th March pre-trial hearing at the Military Commission for The New Arab.

Follow her on Twitter: @KatyRoseStone

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News