The attack on British-American novelist Salman Rushdie at a literary event at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York on Friday shocked the world.

The assailant, 24-year-old Hadi Matar, born in the US to Lebanese parents, leapt onto the stage and stabbed the author 15 times before being arrested by a state trooper.

Rushdie, 75, was left with life-changing injuries but his agent has said his “condition is headed in the right direction”, although it will be a long road to recovery.

Ever since the attack, headlines have been dominated by reports about Rushdie’s health and speculation about the attacker’s possible motives.

Accusations have also swirled about Iran’s potential involvement, given the Islamic Republic’s intimate involvement in a decades-long incitement campaign against the author.

"The fatwa has been a bone of contention between Iran and the West for several decades, triggering episodes of diplomatic rupture and outbursts of aggression beyond Iran's borders"

The Rushdie affair

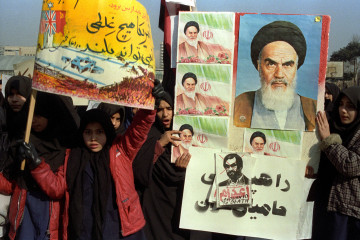

In 1989, the late founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa urging "Muslims of the world rapidly to execute the author and the publishers of the book" so that "no one will any longer dare to offend the sacred values of Islam".

The religious decree was issued in response to the publication of Rushdie’s book, ‘The Satanic Verses’, which the cleric said had insulted Islam.

The book, which has likely not been read by most Iranians, is deemed blasphemous by some Muslims, and according to a plurality of Shia clerics apostasy warrants retribution by death.

Rushdie himself maintains that the novel is about “migration, metamorphosis, divided selves, love, death, London and Bombay,” not Islam.

The fatwa, issued by a pre-eminent Muslim jurist, has been a bone of contention between Iran and the West for several decades, triggering episodes of diplomatic rupture and outbursts of aggression beyond Iran’s borders.

In March 1989, less than a month after Ayatollah Khomeini’s pronouncement, the United Kingdom and Iran severed diplomatic relations.

It was only after the pro-reform government of then-president Mohammad Khatami and his assurances in 1998 not to prosecute the execution of the fatwa, and a pledge to draw a distinction between religious edicts and Iran’s responsibilities as a political actor, that tensions began to dissipate.

However, the successor to Ayatollah Khomeini, the second Supreme Leader of Iran Ayatollah Khamenei, has never recanted the original fatwa and has insisted on occasion that it is irrevocable.

Meanwhile, the 15 Khordad Foundation, a revolutionary entity operating under the aegis of the Supreme Leader, had set a bounty of $3 million on Salman Rushdie’s head, which activists say remains on offer.

The work of the Foundation has since been eclipsed by other parallel conglomerates and wealthy charities including the Mostazafan Foundation and the Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs, and it has mostly kept a low profile in recent years.

However, 15 Khordad Foundation is a subsidiary of the well-heeled Executive Headquarters of Imam’s Directive, with holdings valued at upward of $95 billion.

|

|

Violent attacks

The controversy surrounding ‘The Satanic Verses’ and the polemical Iranian fatwa have generated episodes of deadly violence over the decades.

In 1991, Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator of the book, was fatally stabbed in Tokyo on the University of Tsukuba campus where he was an associate professor of Islamic culture.

That same year, the Italian translator of the book Ettore Capriolo was targeted by a man of Iranian origin at his home in Milan but survived. He was critically injured in his neck, chest, and hands.

In 1993, the Norwegian publisher William Nygaard was shot three times in his back but survived, even though the gunmen were never apprehended.

In one of the most harrowing bouts of violence, the prominent Turkish writer Aziz Nesin, who translated the novel, was hunted by a mob who set fire to the Madimak Hotel in Sivas, central Turkey, where he was attending a conference.

He survived the assassination attempt but 40 people died in what came to be known as the Sivas massacre.

"The controversy surrounding 'The Satanic Verses' and the polemical Iranian fatwa have generated episodes of deadly violence over the decades"

Iran's official response

On Monday, in the first official reaction to Friday's stabbing, Iran denied any link with the attacker but blamed Rushdie for insulting Islam.

"We categorically deny" any link with the attack and "no one has the right to accuse the Islamic Republic of Iran," foreign ministry spokesman Nasser Kanani said.

"In this attack, we do not consider anyone other than Salman Rushdie and his supporters worthy of blame and even condemnation," he said at a press conference.

"By insulting the sacred matters of Islam and crossing the red lines of more than 1.5 billion Muslims and all followers of the divine religions, Salman Rushdie has exposed himself to the anger and rage of the people."

Prior to the statement, state media and hard-line newspapers had openly celebrated the attack, calling it “divine vengeance”, and leading with headlines such as “arrow from nowhere” and the “blinding of the devil”, the latter a reference to reports that Rushdie may lose an eye.

Such responses encapsulated the prevalence of fundamentalist attitudes among certain factions of Iranian society after years of state indoctrination.

The state and civil society

Yet, many Iranians have also been vocal in condemning the targeting of Salman Rushdie and defending his right to free expression, while avowing that they do not agree with his portrayal of Islam and Prophet Muhammad.

A group of 14 prominent Iranian religious scholars issued a statement denouncing attempts to weaponise “different instruments including religion to suppress freedom,” asserting that they don’t believe in an Islam that authorises terror.

They noted that “an extreme, resentful and distorted interpretation of Islam is fundamentally at odds with the traditional reading of the overwhelming majority of Muslims of their religion”.

Mohsen Kadivar, a dissident Iranian cleric, prominent religious intellectual, and research professor of Islamic studies at Duke University, said that the assailant deserves punishment based on Islamic law, adding that there is no religious or Quranic rationalisation for sanctioning the killing of Salman Rushdie, and that with murder and terror, Islam and Iran will only reap hatred.

|

|

Before the foreign ministry’s statement on the attack, some analysts had predicted the official Iranian response.

“I don’t think the Raisi administration will be able to condemn it, [rather] I suspect they will endorse it and call it a matter of executing the law. Think of how Raisi responded to the charges that he was on the death committee,” Ali Ansari, the founding director of the Institute for Iranian Studies at the University of St. Andrews, told The New Arab.

“I think people need to speak out, especially those in positions of political influence. I understand it is very difficult for those living within Iran but at the very least they should not endorse it,” he added.

Despite the Iranian state’s connection with the Rushdie affair as the originator of the fatwa, many analysts say that most Iranians reject extremism and are largely moderate and tolerant in their political views.

“Although there is an extremist political system in power, most studies suggest that Iran is one of the most secular nations in the Muslim world,” Afshin Shahi, an associate professor in Middle East politics at the University of Bradford, told TNA.

"There is a culture war going on between the Islamic Republic and the majority of Iranian people. The vast majority of people in Iran are critical of these extremist policies within and beyond Iranian borders"

“After four decades of the Islamic Republic, there is hardly any appetite for political Islam among various social classes in Iran and such horrific incidents only widen the gap between the state and civil society,” he added.

“As these horrific incidents are taking place overseas, there is a culture war going on between the Islamic Republic and the majority of Iranian people. The vast majority of people in Iran are critical of these extremist policies within and beyond Iranian borders.”

But the gratuitous attack and the fierce debate it has ignited about political Islam and the international footprint of the Islamic Republic certainly run the risk of heightening prejudice against Muslims and stoking Islamophobic sentiments.

Indeed, many observers have blamed the incident on the perceived intolerance of Muslims towards free expression and their disproportionate fixation on a book.

But many prominent Muslims have come forward and renounced violence in the name of religion, insisting that words, not brute force, are the way to defend Islam against criticism.

The Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Malala Yousafzai, quoted her father on the Rushdie controversy in her 2013 book ‘I Am Malala: The Story of the Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban’ as saying, “Is Islam such a weak religion that it cannot tolerate a book written against it? Not my Islam!”

Saeid Golkar, an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Tennessee, says Muslims are not a monolith and it would be erroneous to make broad generalisations about them.

“There are 1.6 billion Muslims who are very different from each other. Some of them are nominally Muslim, some of them are culturally Muslim, some of them are observant and some of them are Islamist. Even not all the Islamists are radical. These differences need to be understood,” he told The New Arab.

“Every time you try to show that Islam is not a religion of violence, and that violence is actually a consequence of the political situation in the Muslim world, something will happen and then all your efforts are destroyed. My guess is that the situation will get more difficult for Iranians and Muslims in general as a result of what has happened,” he added.

Kourosh Ziabari is an award-winning Iranian journalist and reporter. He is the Iran correspondent of Fair Observer and Asia Times. He is the recipient of a Chevening Award from the UK's Foreign and Commonwealth Office and an American Middle Eastern Network for Dialogue at Stanford Fellowship.

Follow him on Twitter @KZiabari

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News