Bombed, shattered, surviving: Syria's schools continue teaching, underground

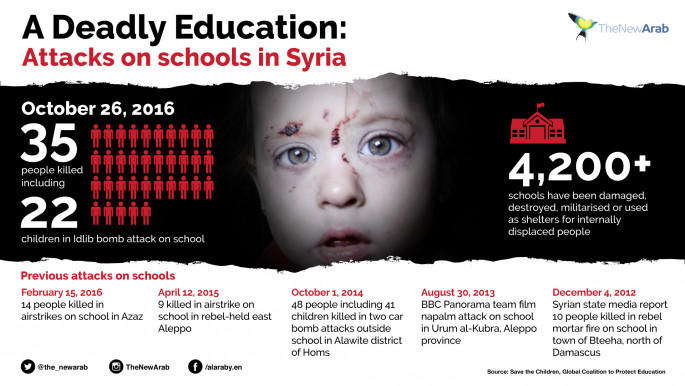

On 26 October when airstrikes hit a school complex in the small rural town of al-Hass in Idlib province in North West Syria their effect was deadly: 35 people were killed in the attack, including 22 children; some of whom died at their desks, in classrooms torn apart by white hot metal.

While shocking, the 26 October attack in al-Hass was not unexpected. In August, aid organisations warned that airstrikes carried out by Syrian and Russian air forces in the rebel-held province, were increasingly putting schools at risk.

In Syria, schools have long ceased to be safe places, and nowhere more so than in East Aleppo.

“There are only three, maybe four schools fully intact left in East Aleppo,” said Abdulkami al-Hamdo, a secondary school teacher living in the area, speaking to The New Arab.

“On my journeys to school I have seen many bombs dropped, some close bye. For the children it is the same.”

School amid the bombs

In 2011, 97 percent of primary school-aged children in Syria were enrolled in school. By 2015 this figure had plummeted to 50 percent. In East Aleppo, where an estimated 100,000 children live, enrolment stands at just six percent today.

Rebel held, but surrounded by pro-regime troops, East Aleppo has been subjected to devastating aerial campaigns carried out by Syrian and Russian warplanes that have left hundreds dead. Even access to basic resources like food, medicine, and potable water is severely limited.

Despite such hardships, school still goes on for some, often in underground bunkers.

“Around 100 houses serve as schools, we use the basements. It is important not to have lots of people in the same place because there is a greater risk of being targeted,” said Mr al-Hamdo, who has a 7 month-old daughter, and has had his own close brushes with death while teaching.

|

On my journeys to school I have seen many bombs dropped, some close by. For the children it is the same. Abdulkami al-Hamdo, a teacher based in East Aleppo |

|

One particular incident, he says, took place on 12 April 2015.

“I had just finished class, and was closing the door,” explained Mr al-Hamdo. “Suddenly, I heard the sound of rockets. I threw myself on the ground … When I got up I couldn’t see anything because there was smoke everywhere.”

“I could hear screaming, students crying,” said Mr al-Hamdo, a solemn tone in his voice. “It was horrific.”

Four teachers and at least six others were killed in the attack which was documented by monitoring groups at the time.

Misty Buswell, Save The Children’s Communications Director for the Middle East and Eurasia, said that combatant forces in Syria have acted with almost complete “impunity” with regards to attacks targeting civilians in Syria.

Over the course of Syria’s now nearly six year-long war, more than 4,200 schools in the country have been damaged, destroyed, militarised and used as detention centres, or been converted into shelters for internally displaced persons, according to UNICEF.

“These attacks have left children dying in their classrooms. “We have to keep raising the alarm, demanding that attacks on schools end,” said Buswell.

|

| Children attend class in a school in the besieged Syrian town of Douma, in the suburbs of Damascus, 5 November 2015 (AFP) |

A generation missing out on education

Although monitoring groups regard the Syrian regime as responsible for the most civilian deaths in Syria, rebel forces have also been accused of attacks that have targeted both schools and hospitals.

Only a day after the devastating 26 October attack in al Hass, six children were reportedly killed in rebel shelling of a school complex in regime-held West Aleppo. Rebel groups also stand accused of perpetrating a deadly double car bomb attack outside a school in Homs that claimed the lives of 48 people, including 41 children, in an Alawite neighbourhood in October 2014.

In East Aleppo, where living conditions are among the worst in all of Syria, Buswell noted that even moving schools underground was no guarantee of safety from munitions including barrel bombs, and even naval mines, used in attacks on rebel-held districts.

“There are children in Syria growing up now that associate school with death,” said Buswell. “This is the future generation, they are going to have to rebuild and deal with reconciliation. This is not going to be possible if people do not access education due to fear.”

Aid organisations and rights groups have also pointed out that dwindling school attendance rates — particularly in rebel-held areas — in the short-term, have pushed children into the labour market, fuelled migration and in the case of girls, lead to disturbing increases in child marriage.

But, even following global condemnation of the 26 October strike in al-Hass, schools have continued to fall prey to attacks. Most recently, on 6 November, four children were reportedly killed, and another nine injured by reported regime mortar fire while attending a kindergarten in Harasta, a northeastern suburb of the capital Damascus.

“When someone is absent we fear the worst,” said Mr al-Hamdo, speaking from East Aleppo. “Some students have lost their entire families. Others have had their homes destroyed. We hardly ever see the same faces for long, children move to other places when there homes are destroyed, and then other families and children move in and replace them.”

| Read more: Bomb our schools in Syria? We'll build more |

The spark that lit the flame

Attacks against school children have been a disturbing feature of Syria’s civil conflict from the outset.

In February 2011, the detainment and torture of a group of school children by regime forces in Daraa sparked angry demonstrations in the city whose violent repression sparked nationwide protests that eventually gave way to all out conflict.

Later, in 2012, as conflict spread across the country, the Syrian regime’s Ministry of Education lost control of schools in areas controlled by rebel forces. Fledgling opposition bodies based in Turkey sought to establish organisations in order to develop a new curriculum and textbooks free of perceived slants, even factual inaccuracies, located in state-distributed textbooks.

One often cited example of such a slant, can be found in the placement of Hatay within Syria’s borders in maps in history and geography textbooks despite the fact that this territory was annexed from Syria by Turkey over seventy five years ago.

|

There are children in Syria growing up now that associate school with death. This is the future generation, they are going to have to rebuild and deal with reconciliation. Misty Buswell, Communications Director for the Middle East and Eurasia, Save The Children |

|

But today in East Aleppo, Mr al-Hamdo said that due to shortages of equipment and teaching materials some schools had resorted to using the pre-existing state textbooks.

“At least we have books at all, sometimes we have to share — one textbook between three, four students,” said Mr al-Hamdo, explaining that teachers often played the role of counsellors to their students.

“In an English lesson, you might want to use the word “mother” or “father” when providing an example to make a point but if a student has lost a parent this can cause distress. We have to be sensitive.”

In the last few weeks, rebel forces have mounted a number of desperate attacks in order to break the siege of East Aleppo, but to little avail. Meanwhile, a Russian-proposed humanitarian “pause” in the city has presented residents with an ultimatum to leave the area via a number of safe corridors or stay and face further bombardment.

Few have left East Aleppo raising concerns that further violence is imminent as the Syrian regime pushes to secure control of a city it views as crucial to winning the war.

“Many feel it is too humiliating to leave. They would rather stay and die,” reflected Mr al-Hamdo, who said that he did not plan to leave Aleppo, but instead wanted to continue teaching, a profession that he says circumstances have increased his commitment to. He said that many of his students felt the same.

“Often if there is shelling we tell students not to come to school, sometimes it lasts one week, two weeks. Sometimes there is no electricity. We often do not finish the courses on time. But we develop close relationships with students.”

“Before the war students were reluctant to go to school. Now, sometimes I go to class and the students are there half an hour early. It can help give the students and staff a release. But it is not easy,” explained Mr al-Hamdo.

“We are surrounded by death and destruction, but we still have hope.”

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News